The Hays Humm - December 2021

The Hays Humm

Award Winning Online Magazine - December 2021

Tom Jones - Betsy Cross - Constance Quigley - Mimi Cavender - Steve Wilder

by Tom Jones

“Texas is the land of perennial drought, broken by the occasional devastating flood.”

https://www.twdb.texas.gov/newsmedia/drought/doc/weekly_drought_report.pdf

For the previous 6 months Hays County has experienced a significant wet weather cycle. In October over 7.5 inches of rainfall was measured at my house in Wimberley. Another 3 inches was collected in November. The weather patterns in Central Texas include alternating wet and dry cycles that can last for months. Similar to last year, Texas is headed into winter while La Niña conditions prevail and drought is expected to expand. The next next 6-7 months is likely be a dry cycle, including months of low rainfall and possibly a drought in the summer. Let’s look at the data and what they reveal.

Aquifer health is assessed by comparing a water well’s current level to its range of water levels between 2008 and 2019. The northern and south-central regions of Hays County currently indicate that the Middle Trinity "Cow Creek" aquifer levels are approaching their lowest since 2009. The Dripping Springs and Wimberley/Woodcreek high volume water supply wells are included in these historical low water levels. The Mt. Baldy well in Wimberley is also at its lowest since late 2000. The aquifers have seen a small recovery due to the recent rainfall events but are still below normal conditions.

Drought Indicators

Hays County is not currently in a District-wide drought. The Blanco and Pedernales Rivers are currently flowing at normal conditions. Jacob’s Well (JW) represents aquifer conditions within the Cypress Creek watershed and is used as a drought and groundwater health indicator for the Jacob’s Well Groundwater Management Zone. The spring is currently flowing at or above normal conditions. Due to the recent rains, the Jacob’s Well area is not in drought for November. The October rains and the cooler temperatures allowed the water levels to recover a little during November. This recovery is critical as the probable La Niña weather phenomenon is expected to bring a drier and warmer than normal winter.

The Hays Trinity Conservation District recently published historical flow rate charts for JW and the Blanco River. The charts below include data for the past two years. So much data is stuffed into the plots, it is difficult to understand what it is telling us. Note that the Blanco River has not reached drought conditions for the past 2 years.

Wimberley Area Water Conditions

Click Charts to enlarge: Ref: Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District - Oct 2021 report

Blanco River

The Blanco River chart illustrates the cyclic nature of Wimberley’s water table over the past two years. The most recent dry cycle continued for 7 months, from December 2020 to June 2021. This represents the lowest streamflow level in the past 2 years. The current wet cycle started in May 2021 and continues through November of this year. It’s easy to see the higher streamflow spikes associated with a wet cycle on the chart.

Note that the Blanco River plot looks much different than the JW graph. The river has much higher flow volumes than the relatively small discharge from JW spring. Currently the Blanco River is within its average flow rate for this season. Note the increased water flow spike at the end of the chart from the significant October rainfall.

Jacob’s Well - Cypress Creek Watershed

The JW chart also shows the cyclic nature of its springflow level from the vital Cow Creek aquifer. Similar to the Blanco River, the last dry cycle extended 7 months before changing to the wetter cycle six months ago. It continues today.

Over the past six months, JW has experienced spring flows at or above normal conditions. The welcome high flow spike in October 2021 is due to rain events, which are shown on the chart. This recovery compares to January of this year, when there was discussion of JW dropping to zero flow. What a nice recovery!

Good water recharge to the Middle Trinity aquifer has been sustained from the consistent rainfall events during May-November 2021. The top right corner of the graph shows the rainfall data for 2021.

The Forecast

“There is no way that we can predict the weather six months ahead beyond giving the seasonal average”

There are a number of reports predicting that La Niña will soon return with its reduced rainfall and dryer weather cycle. Given the wet November, I expect December will show dryer conditions moving into the Hill Country. It will be interesting to see if the 7 month cycle of wet vs dry conditions will continue. If the dry cycle returns in December or January, the next wet cycle may not return until summer of 2022. If not, it could be a long dry summer and the return of drought conditions.

Meet Your Master Naturalist

Andrew Rider

About me: I grew up in Austin, Texas, and kicked around for a while before deciding to earn a PhD in computer science at Notre Dame. I interned at NASA for a summer and then went to work in San Francisco, where I met Irene. We both now work for ourselves from the home we’re building by hand together in San Marcos, Texas.

You may not know: I love growing plants from seed and learning which native plants are safe to eat. My favorites that I’ve tried so far are agarita, prickly pear, and turk's cap. My hobbies are researching artificial general intelligence, playing the ukulele, and gardening. Also, Irene and I are writing a science fiction book for fun in our spare time.

Favorite Master Naturalist Project: I like working with HELM, too! I enjoy being out in nature and telling other people about it (especially about edible plants).

Bird I like the most: Roadrunners. The way they move reminds me of dinosaurs.

Irene Foelschow

About me: I was born and raised in Southern California. I moved to the Bay Area for college and stayed there to begin a career in marketing. A couple of years in, my interest in marketing faded, and I decided to switch to software development. After some intensive training, I landed a job at Google. Eventually, I moved on to a smaller company where I felt my work had a higher impact. Another year went by, and Andrew convinced me to move back to Texas with him to marry and be near his family. I never dreamed of moving outside a major city, but I’m happier than ever living on five acres of beautiful oak forest in San Marcos.

You may not know: I was lucky enough to spend a semester in high school studying in Kumamoto, Japan. In college, I taught English for a summer in Guangzhou, China. When I was in marketing, I travelled to Helsinki, Barcelona, Shanghai, and Tokyo for work.

Favorite Master Naturalist Project: HELM!* I loved learning to use QGIS to create maps for landowners, and I love identifying new plants out in the field. If there are any other projects with technical needs, I’d love to help.

Bird I most identify with: I’m not a very good birder, but I spent quite a bit of time watching during the Great Backyard Bird Count. I remember being thrilled when I was able to use Merlin to identify a hermit thrush. I don’t think I have much in common with them, but they’re my favorite. The little spots on their breasts are very cute.

* HELM (Habitat Enhancing Land Management)

Thank You Contributors

Mimi Cavender, Art Crowe, Bob Currie, Irene Foelschow, Eva Frost, Lilita Olano, Susan Nenney, Constance Quigley, Andrew Rider, Steve Wilder

HaysMN Lilita Olano has published her first children's book

Buenos Dias, Gioia / Good Morning, Gioia is about all the friendly animals that come to visit me every morning at the top of a hill in Wimberley, Texas, where I live. They include deer, lots of birds, foxes, and a rabbit. Diego, my son and Gioia’s father, asked me to write a letter to their baby before she was born. The letter became a poem, which then turned into this book. Uncle Santi and Aunt Sarah wrote the English translation. Roberta Wright, Gioia’s grandmother, made the delightful illustrations. Gioia has brought joy to the whole family. I think the book will be appealing to very young Master Naturalists and their parents and grandparents. It is available for purchase on Amazon.

by Art Crowe - photo reference: educationinaction.org

The year was 1685, just three years after Robert Cavelier de La Salle had discovered the mouth of the Mississippi, when he found himself stranded in Texas. He had left La Rochelle, France, on July 24, 1684, with about 200 settlers, six missionaries, eight merchants, numerous artisans and craftsmen, and over a dozen women and children on a multi-pronged expedition with religious, commercial, and military objectives. The flotilla of four ships left France with the king’s approval. The 34-gun warship of the Royal Navy, Le Joly, with a crew of 70 was to provide protection during the voyage. The lightly armed cargo vessel, L’Aimamble, had provisions the settlers would need, as did a smaller vessel, Saint-Francois. The latter two vessels were under lease to La Salle just for the journey and were to return to France with the Joly. La Belle was the only vessel meant to stay with the settlers. The Belle was built over a four month period in 1684 and was initially intended to be carried over disassembled in the hull of the Joly. It soon became apparent that there wasn’t enough room. So the 51-foot ship that was designed for the Mississippi River was forced to sail the Atlantic. Off the coast of Saint-Domingue (Haiti), the Saint-Francois lost sight of the Joly and was captured by the Spanish. This was doubly bad because not only did they lose important provisions, but they also notified the Spanish of their intentions.

Bullock Museum: Reconstruction of La Belle - Ref: Wikipedia.org

Model of La Belle - Ref: Wikipedia.org

La Salle is quoted as saying that the Mississippi “lay at the far end of the bow in the Texas Coast,” which today is called the Coastal Bend of Texas. When they first sighted land on January 1, 1685, they were off the coast of western Louisiana. Small boats were sent ashore, where they found an impenetrable marsh. Here they lost sight of the Joly and would not meet up again until January 19th. Sailing westward, La Salle on January 16th ordered the Belle’s captain, Daniel Moraud, to hold close to shore, where they found a bay which appeared rather deep with an island between its headlands. La Salle believed this to be the mythical Espiritu Santo Bay; it was probably Galveston Bay. On January 14th, they were off the mouth of the Brazos River, where they noted deer and bison on the beach. A surviving page of the Belle’s logbook puts them on January18th at a point mid-way between Corpus Christi Bay and Baffin Bay. The pilot of the Belle, Elie Richaud, began keeping a secret record at this point because he believed that La Salle had intentions other than just finding the Mississippi River. This was, however, the southern-most record of their travels. This notion that La Salle had other objectives than the Mississippi is supported by the Sulpician abbot d’Esmanville who relates a conversation he had with La Salle on January 20th in which La Salle is said to have said that he was not as concerned with finding a river as with taking soldiers and confronting the Spaniards in Nueva Vizcaya, the gold and silver mining area of northwestern Mexico that the King of France had designs on.

For his part, La Salle still thought he was near his river. So he focused on this objective first. He ordered soldiers ashore on January 30th on Matagorda Island and sent them on a northeast course looking for the river. The Belle was to stay close by to give aid if necessary. Trouble with heavy seas caused the Belle to lose an anchor which made that mission impossible. By February 8th the 100 or so soldiers made their way to present day Pass Cavallo, where they were stalled. On February 6th, the Joly gave the Belle an extra anchor. La Salle eventually caught up with them there and concluded that this was one of the mouths of the Mississippi. In fact, he was about 400 miles from that objective.

What happened on February 20th at Pass Cavallo was strange indeed but in line with the way La Salle conducted himself. When presented with an important event, he became absent from the event itself. On the morning of February 20th, he saw fit to go out early in the morning with some laborers to cut a tree for a canoe. He left Captain Claude Aigron in charge of bringing L’Aimable through the narrow pass. The pilot of the Belle offered help as did the Joly in case L’Aimable was to run aground. Captain Aigron refused all assistance. At ten in the morning, a second pilot rowed out to L’Aimable and asked Captain Aigron how much water his ship drew. When told that it was 8.5 feet, they advised him not to enter because the shoal was hardly deeper and the swells were high. The expedition’s engineer, Jean-Baptiste Minet, would write in his diary that “the wine that M. de La Salle left for the captains and pilots had rendered them more daring than necessary.” Whether drunk or just arrogant, Captain Aigron did in short time run L’Aimable hopelessly aground. La Salle would go on to write up an official document that was to be taken back to France with Le Joly’s Captain Beaujeu accusing Captain Aigron of willfully running the ship aground and then confusing all efforts to float her off and salvage the cargo.

The Settlement

So instead of getting ready to sail back to France, the Joly’s sailors worked through the night to salvage what they could from the wreck with ship’s launches and canoes. The salvage effort continued on and off, weather permitting, for several weeks. During this time, it was recorded that men were dying at a rate of four or five per day due to their ingesting brackish water and “wretched food.” Karankawa Indians began to show up, around 100. At first, there were successful bartering efforts between the two groups, but when some of the Indians took some blankets, relations soured. In mid March, Le Joly left the colony on what was to be a year-long return voyage back to France. On March 22nd, L’Aimable broke apart and scattered the remaining goods into the sea. Efforts began to find a more suitable place to establish a settlement. On April 2, 1685, the encampment was moved about 50 miles to Garcitas Creek, where there was fresh water and abundant game in the form of buffalo herds. In addition, there were deer, turkeys, prairie chicken, waterfowl, and fish. The colonists brought with them a small herd of eight pigs that by the time they finally left in January, 1687, numbered seventy five. Here La Salle established what he called Fort St. Louis. It was really a four room house made with salvaged lumber from L’Aimable. It did, however, have eight cannons that had been salvaged, but not any cannon balls. Here was established the first Christian house of worship in Texas. Here the first marriage was recorded. And here the first birth of a European in Texas was recorded. Besides these few things, not much of a positive nature happened at the settlement. Most of the settlers were forced to sleep outside; the rooms were reserved for La Salle and the clergy. Other than buffalo, food was scarce. People were forced to forage on the land to find substance. Being unfamiliar with the native vegetation, many of the settlers fell to the sweet tasting but deadly tunas from the prickly pear cactus. They failed to peal off the spines and choked to death. One of the victims was the Captain of La Belle, Daniel Moraud. The pilot, Elie Richaud, became the Belle’s new captain. His tenure was brief, however. La Salle returned from one of his explorations of the bay in late December to find Richaud and five of his companions murdered in their sleep by the Indians. La Salle put the second mate, Pierre Tessier, in charge, a decision that was to prove costly. It was early January, 1686 when La Salle set out on what he thought would be a short 10-day journey to reconnoiter the bay with 20 men. By the time he returned on March 15th with only eight men, there was no sight of La Belle. Tessier, claiming lack of fresh water, availed himself of the sacramental wine on a daily basis and was rarely sober. It was a poor decision on his part when he attempted to cross the bay during a strong north wind. Lacking a proper crew to man the rigging, the ship began to drift toward Matagorda Peninsula. They put their only anchor over, but it did not hold. They were too weak, or too drunk, to attach one of the cannons as an extra weight. Lacking a proper anchor, the ship plowed head first into the shallows, approximately a quarter mile from shore. This was the fourth ship under the command of La Salle that was lost, each one more costly than the last. It should also be noted that he was not present when any of them sank.

The Aftermath

The survivors moved what they could to the peninsula, leaving behind one of their crew mates in the forward deck under a coil of rope. Here he lay for over 300 years until archeologist recovered his remains along with what remained of La Belle. From this point on, the settlement declined rapidly. By the end of July, La Salle himself acknowledged the loss of half his people. Illness and death were everywhere, as were the threats from the Indians. On January 12,1687, La Salle took with him 17 men on an attempt to walk to the Mississippi. He left behind 40 individuals. Over the next three months they crossed the Navidad, the Colorado, and the Brazos Rivers and ended up near the Trinity River. Then on March 19, 1686, a group of malcontents led by Pierre Duhaut, an original investor in the expedition, assassinated La Salle with a single shot to the forehead. This was the fifth and final attempt on La Salle’s life. They left his naked body in the brush for scavengers to find. From here the seven remaining men set out for Canada. By September 3, 1686, 15 weeks later, they had made it up the Mississippi to the more placid waters of the Illinois River. This was French Territory, and it was an easy paddle from there to Canada. Eventually, a handful of those surveyors, including the drunken second mate Tessier, made it back to France, each to give their accounts of the expedition and where fault might lay.

The colonial Spaniards launched six separate land expeditions and five sea searches looking for the French colonists. On April 4, 1686, the Spanish discovered the remains of a broken ship with three fleurs-de-lys on her stern. The threat of France establishing a colony somewhere between New Spain and Florida was one of the main reasons for the establishment of Spanish Missions in Texas.

With the waters of Matagorda Bay held back by massive steel cofferdam walls, archeologists uncover the wreck of La Belle from its tomb of muddy sediments. Photograph by Robert Clark.

The Recovery

The Texas Historical Commission (THC) commissioned independent researchers in 1977 to search archives in France for maps from the time. They found detailed records made by the expedition’s engineer, Jean-Baptiste Minet, which marked the location of both L’Aimable and La Belle. It was not until funding became available in 1995 that the THC organized a magnetometer survey using differential GPS positioning. Divers recovered several bronze cannons with markings linking them to the period. The decision was made to construct a cofferdam around the wreck site. This was a double-walled steel structure, with compacted sand between the two walls. After completion in 1996, water was pumped out from the inside of the cofferdam and the archaeological excavation began in earnest. This endeavor lasted from July, 1996, to May, 1997, and is considered one of the most significant maritime excavations of its time. Texas A&M University’s Nautical Archaeology Program was in charge of preserving all the artifacts. The hull was treated by long-term soaking in polyethylene glycol and freeze-drying. This process took over ten years to complete. The entire hull that remains is on view at the Bullock Texas State Historical Museum in Austin. In addition, there are displays of tools, religious artifacts, cooking utensils, and trading goods that give detailed insights into life during the middle of the seventeenth century.

References

The Wreck of the Belle, the Ruin of La Salle. Robert S. Weddle. 2001. Texas A&M Press. 327p.

La Belle (ship). Wikipedia. 2021. 10p.

BEAUTIFUL DAY… at Arnosky Family Farm

“We were there yesterday afternoon [November 2], and there were thousands of monarchs in the marigold field. Hypnotic.” — Susan Nenney

Click on the photo below to see Susan’s video. To replay the video, click the circular arrow icon that appears in the lower left corner of the photo after your initial viewing:

Video by Master Naturalist Susan Nenney

BEAUTIFUL NIGHT… for a rare Beaver Moon

“At 3:00 a.m. thick clouds rolled in over Owl Tree and obscured my view at the peak of the longest partial lunar eclipse (97% covered) since 1440. But with Orion rising in the southeastern sky, the first half was a beauty. November 19, 1:00 a.m. - 2:45 a.m.” — Betsy Cross

Moon shots by Betsy Cross

According to The Old Farmer’s Almanac, monthly full moon names are tied to early Native American, Colonial American, and European folklore. November’s Moon names highlight the actions of animals preparing for winter and the onset of the colder days ahead.

This November’s full moon is called a Beaver Moon because it’s the time of year when beavers begin to take shelter in their lodges, having laid up sufficient stores of food for the long winter ahead. During the time of the fur trade in North America, it was also the season to trap beavers for their thick, winter-ready pelts.

Furthermore, the Almanac references some alternative names. Digging (or Scratching) Moon, a Tlingit name, evokes the image of animals foraging for fallen nuts and shoots of green foliage and of bears digging their winter dens. The Dakota and Lakota term Deer Rutting Moon refers to the time when deer are seeking out mates, and the Algonquin Whitefish Moon describes the spawning time for this fish.

In reference to the seasonal change of November, this Moon has also been called the Frost Moon by the Cree and Assiniboine peoples and the Freezing Moon by the Anishinaabe.

We’ve spread our wings!

The Hays County Chapter of Texas Master Naturalist™ has completed an eventful year 2021, and high flight was worth the effort. We not only adapted to this second year of Covid-19 restrictions, we upped our game and thrived in a brave new virtual world. An eager, young-skewing training class seemed unfazed by Zoomed presentations and masked field trips and joined veteran members in cautious outdoor volunteer work and two ambitious new educational outreach programs. We all enjoyed exceptionally high-quality presentations in the monthly virtual Chapter Meetings—a victory echoed at November’s hybrid State Meeting, where three of our Hays Chapter members were outstanding presenters. Yes, we’ve got the Hays Chapter humming.

But just look back at 2021’s natural gifts to us: a stronger variant of a novel human virus, a bird virus, a killer freeze, belated spring, Wormageddon, rain just short of flooding, and the spectre of another late summer drought! This year was a naturalist’s worse nightmare in this pocket of Texas Hill Country, where already the rocky soils, the heat and floods and encroaching suburbs routinely make for fitful sleep.

The Hays Humm can be imagined as a modern naturalist’s journal. Please enjoy the Archive of this year’s issues, where we can skim each month’s content to review this extraordinary year for HCMN: 2021, the year we fretted, fluttered—and fledged. The whole Chapter—with new outreach programs, enthusiastic volunteers, burgeoning training classes, and this newly expanded magazine—is flying high!

In February 2021 The Hays Humm, spreading its wings, redefined itself as distinct from the Hays County Master Naturalist website and the chapter-business function of a typical newsletter; it began its first full year as an online magazine, linkable from the Chapter website.

Articles grew somewhat longer and enlisted Chapter members’ contributions. Members immediately responded with first-person reports and photos documenting the local effects of the North American Pine Siskin virus.

The March issue covered The Big Chill—a week of snow, ice, and sub-freezing temperatures across Texas that paralyzed business and travel, shut down the electrical grid, shattered plumbing, stressed wildlife, destroyed crops and gardens, browned out live oaks, delayed spring green-out, froze bat populations (and, tragically, people) but, oddly, seemed not to affect bird populations at our feeders.

Again HCMN members provided stunning documentation in words and pictures of an historic weather event. That issue also announced the launch of HCMN’s important new educational outreach to area landowners, Habitat-Enhancing Land Management (HELM).

With spring delayed almost a month by the Big Chill, April’s issue offered members’ reports that the Texas Hills had certainly been Chilled, but Not Killed. Your texts and photos surveyed dead, damaged, and heroically recovering species.

Our May issue continued to document April’s late but robust Hill Country spring.

But just when we thought we were safe, we faced Wormageddon—a statewide over-abundance of various moth larvae: inchworms and leaf-rolling caterpillars. The freeze had killed two depredating wasp species, allowing a devastating caterpillar explosion. All that late and tender spring foliage had finally recovered from the Deep Freeze, only to be eerily webbed and stripped bare again. This year, especially for our live oaks, there were actually two springs.

After the “snowpocalypse” and “wormageddon” of 2021, it was almost miraculous to see flowers in April. I was amazed at the resilience of so many of our native plants and trees. Many awakened at their usual time, and others took two weeks or more to recover and begin their springtime bloom cycle. I was particularly happy to find my anacacho orchid tree had survived the freeze and rewarded me with its sweet-smelling flowers. It is currently blooming (end of April), fully two weeks behind its 2020 blossom date. These signs of spring were particularly welcome this year!! — Constance Quigley

June’s issue featured Hays Humm co-editor Betsy Cross’ photo journaling her backyard hummingbird families, laying the groundwork for her wildly successful presentation at the Texas Master Naturalist™ Annual Meeting this November. Her “Resurrection Birds” were survivors, as were the many species of Central Texas’ flora and fauna that bounced back from 2021’s horrific winter and spring.

In the July issue Hays Humm editor Tom Jones documented the hydrogeology of Cypress Creek following June’s 3.6 inches of rainfall.

This July issue and the August issue covered the launch of our Chapter’s second major education outreach program in 2021, Wild About Nature (WAN). Engaging Hays County children and their families, the hands-on displays and nature conversations debuted at Wimberley’s Blue Hole Regional Park during the summer swimming season.

Also in this issue is the third report on Wild About Nature’s family education outreach at Blue Hole Regional Park. This was the Amphibians display led by Lee Ann Linam, and the faces tell the story. WAN’s pop-up appearances at Blue Hole in 2021 strengthened our presence in the community. Our calendar is already filling up with 2022 events in Wimberley, Kyle, and Buda.

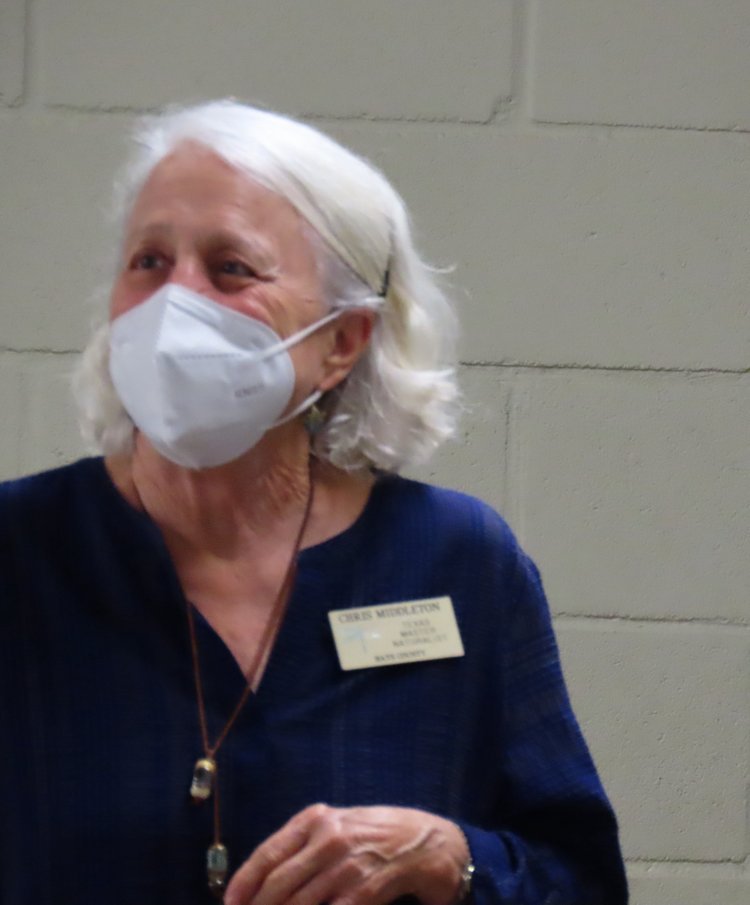

The Blue Hole pop-ups would finish out the year with the huge Boo! Hole Halloween event reported in the November issue. Both WAN and the landowner outreach program HELM are led by Christine Middleton. Both programs signal our Chapter’s expansion of service to the Hays County community during this extraordinary year.

The September issue brought into sharp focus the need to preserve Hays County’s wild habitat. This first of several articles inspired by Doug Tallamy’s vision of “home grown national parks” reminded us of Texans’ historic conflict between their love for and their use of the land. When that use of Texas’ 96% privately-owned land includes seemingly unrestricted urbanization, our urge to conserve wild habitat deepens: not only can we create islands of wildland, but we can connect them in larger, more secure, “archipelagos.”

October’s issue was a Halloween romp through spiders and other traditionally spooky species, jack-o’-lanterns, and ghost stories from the Devil’s Backbone.

There was also a follow-up to Steve Wilder’s Archipelago article. It presented a persuasive counter-argument involving “the edge effect,” as explained by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department ecologist Dr. Louis Verner in the Texas Master Naturalist Statewide Curriculum.

He argues that the smaller the native habitat island, the closer the supposedly protected species are to the edges, where they are exposed to injury, pollution, and predation. Counter-counter arguments are that the archipelago’s interconnectedness would counteract the edge effect, and everyone’s connected little bits are better than losing native habitat altogether. And while we’re working toward better education and legislation, we can start now creating our native islands; we can walk and chew gum.

With the November issue, we were nearing the end of this year of our Chapter’s expansion in membership and outreach, a year of more assertively championing the natural world even while we were beset by flood, cold, pests, and plagues—everything that the natural world could throw at us. Doesn’t it feel like she’s trying to shake us off the planet? Like a dog with fleas. We began the issue with a new push against light pollution. We remembered nature’s (our!) need for dark nights. We reviewed the various organizations linked loosely or closely with the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA). We intend to continue with a Dark Skies: What We Can Do Now follow-up piece early next year.

The November issue also reported on the TMN 2021 Annual Meeting, a hybrid event, featuring a diverse lineup of presenters, including three of our own Chapter members: photography prize winner Betsy Cross on bird photography, Tom Jones on Hill Country karst, and Cindy Luongo-Cassidy on a curriculum set for learning about light pollution; it’s been Cindy and Friends of the Night Sky facilitating our Magazine’s new focus on efficient sensible lighting for dark healthy nights.

Which brings us to now, the December issue, where member-contributors give you more of what keeps us all coming back for those recertification pins.

May we all enjoy Holidays filled with love, joy, and peace.

The Hays Humm staff thank you for your contributions and ask you to keep them coming. We’ve fledged. We’re flying!