The Hays Humm - April 2021

The Hays Humm - April 2021

Award Winning Online Magazine

Tom Jones - Betsy Cross - Constance Quigley - Mimi Cavender - Steve Wilder

Right Here at Home — In the Hill Country

WHO’S NESTING IN YOUR YARD?

Betsy Cross

Some of us are fascinated by the mysterious methodologies of birds building nests and fledging their young. I’ve been peering into bird nests for as long as I can remember. But when I discovered that one could put a wooden box on a pole and periodically open a hinged door to see a bird’s eggs and chicks inside, then watch the parents deliver food and eventually coax fledglings out to take their first flight, I was hooked.

Every year about this time, bird enthusiasts and citizen scientists across the country begin monitoring bird boxes, nest cams, natural cavities, and other nesting habitats to get an intimate glimpse into the secret lives of birds. We log the data to help experts track reproduction numbers; understand migration patterns, the impact of habitat loss, and the effects of climate change; and ultimately, to diagnose the viability and well-being of a species.

Each bird species has a unique nesting style. Nest placement and construction preferences are specific to the species. In some species, both parents work together to construct the nest and take turns incubating the eggs and bringing food to hatchlings. For others, it’s a single parent event, start to finish. Some bird species parasitize the nests of other birds, laying eggs in the nests of a different species, and leaving the rearing of young up to the foster parents.

The closer I watch and observe the nesting patterns and preferences of different birds, the more I consider questions such as these:

Why do some birds build open-air nests in the crook of a tree branch while others are cavity nesters?

What would drive an Eastern Phoebe to choose a half-inch ledge under my front porch onto which it applies mud in the form of a cup, then covers it with soft trailing moss, and lines the cup perfectly with a single homogeneous grass in a perfect oval?

Why does an Ash-throated Flycatcher build a nest foundation of Ashe Juniper strips and then cover it in heavy pelt-like layers of animal fur?

Why do titmice add a piece of snakeskin to their nests of fresh green moss lined with soft fur (and sometimes with pink insulation or other artificial stuffing)?

These unique qualities are the signatures of birds.

Project 702 RM Bluebird Nestbox Monitoring

I’ve monitored bird boxes for over 10 years, the last four years at Jacob’s Well in Hays County under HCMN Project 702 coordinated by HCMN Bonnie Tull. I’ve documented five species of birds that utilize the 11 nest boxes across the 81-acre property at Jacob’s Well. The Eastern Bluebird is our target species for habitat enhancement. Their populations fell in the early twentieth century when aggressive species such as European Starlings and House Sparrows were introduced. These non-native species made available nest holes increasingly difficult for bluebirds to hold on to. In the 1960s and 1970s the establishment of bluebird trails and other nest box campaigns alleviated much of this competition, especially as people began using nest boxes designed to keep the larger European Starling out. Eastern Bluebirds have been recovering since. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Eastern_Bluebird/lifehistory

Through Project 702, HCMNs are contributing to the creation of additional habitat for bluebirds. So you might ask, what about the other four species that are using the boxes? Well, I do not discourage nest box occupation by the other species listed here, though proper placement of nest boxes for use by bluebirds is an important consideration and priority.

In addition to the boxes at Jacob’s Well Natural Area, I’ve documented some of these same birds, and others, accessing and nesting in natural cavities on that property. The following images are all part of my contribution to Project 702 at Jacob’s Well. Let’s take a look.

Eastern Bluebird Sialia sialis

Black-crested Titmouse Baeolophus atricristatus

Bewick's Wren Thryomanes bewickii

Ash-throated Flycatcher Myiarchus cinerascens

Carolina Chickadee Poecile carolinensis

Life in A Dead Tree

It’s interesting and educational to monitor and document birds in nest boxes, but I never miss a chance to look for other nesting behaviors along the way. Cavity nesting birds, such as the ones above, utilize old woodpecker holes too, and they can provide fascinating birdwatching opportunities.

In the early Spring of 2018, I noticed a lot of bird activity—bluebirds, chickadees, woodpeckers—around a dead tree on the west side of the path at Jacob’s Well between the upper parking lot and “The Well.” I looked closely and discovered that these cavity nesters were exploring a woodpecker hole. Eventually the Ladder-backed Woodpeckers won the battle for occupancy. After all, it was a woodpecker hole, and maybe they were the original creators.

March 9 - First photo of the male cleaning out the nest. I photographed him each week throughout the nesting cycle. Sometimes he would be peering out when I arrived. Other times if I waited a bit, he would fly in.

March 31 - When he did not appear spontaneously, I would make some clicking sounds until he poked his red head out to see me. He was never camera shy.

April 13 - Finally I photographed the female. She was delivering food to the nestlings. You could hear them chirping in the nest when she arrived.

April 22 - Female Ladder-backed Woodpecker (?) final photo. I did not get to see the fledglings leave their nest.

Then in the Spring of 2019, a new tenant moved into the dead tree—the same tree used by the woodpeckers the previous year. If you look closely at the first photo (or click to enlarge it), you will see the woodpecker hole about 1/3 of the way up, just about level with the top of the oak in the background. A closer look at the tree reveals an Ash-throated Flycatcher on the high left perch. That spot, and especially the limb on the right side in closest proximity to the hole, served as “staging perches” for the parents tending the nest.

The first flycatcher swoops in and lands on the highest perch above the hole. It appears to be on guard duty—a sentry? As it surveys the landscape, the second bird arrives.

The mate flies in with the food and lands on the other staging perch, pausing perhaps to evaluate any risk of a predator before approaching the nest.

After some consideration, the second flycatcher glides down to the hole from the staging perch and delivers the food to the nestlings.

In the Spring of 2020, an Eastern Bluebird couple found its way into the dead tree and raised a family. On one occasion, I observed the male bluebird defending its turf at the woodpecker hole. The aggressor appeared to be the Ash-throated Flycatcher.

May 10 - The male bluebird brings the female in to evaluate the woodpecker hole as a potential nesting site. They study the landscape from the staging perch as she considers the situation.

The male flies down to enter the hole, showing off his flashy blue beauty.

He looks back and invites the female to join him. She does, and she says ‘yes, this will do.’ Soon she will start building the nest with loosely woven grasses. She will lay 2-7 eggs, one per day. She will not begin incubating them until the last one has been laid.

June 14 - The female bluebird stops on the staging perch before delivering food to the nestlings. The bluebird pair has been tending the nest for over a month.

Today much of this tree has fallen away, and the only remaining limb is the staging perch on the right. I am curious to see how the degradation of the tree and loss of these key perches may impact its use. So far this spring, I’ve not seen any activity at the site. Other trees with woodpecker holes at Jacob’s Well have supported diverse families of birds, such as one on the far southwest side that has hosted Bluebirds, Golden-fronted Woodpeckers, and Ladder-backed Woodpeckers. Its primary large limb collapsed at the end of last year. And I’m sure the same will happen quite soon for this tree as well. But as I’ve had the good fortune to watch both of these trees for the past few years, their contribution to sustaining a healthy mix of diversity has been substantial. As long as a dead tree doesn’t create a safety concern, it should be left to provide its final gifts in the form of nesting habitat as long as it can.

Meet Your Master Naturalist

Brent Jackson

Brent & Audrey Jackson,

happiest when hiking.

(Did you know it’s not truly a hike until you get lost?)

About Myself: I grew up in California and didn’t arrive in Texas until 1998, when my meandering career path brought me to Austin, but have really grown to love it. Professionally, I’m a computer geek who first started programming on punch cards in the 70’s. I still love to write code and figure things out on the fly.

That permanent smile on my face is thanks to my wonderful wife and best friend, Audrey, who discovered and talked me into this whole Master Naturalist thing. We are proud Foxes, class of 2018, and proud parents of 4 great young adults.

I have too many hobbies to do any of them well: hiking, gardening, beekeeping, robotics, and generally futzing around in my workshop.

You May Not Know: We started a homestead on 6 acres this year, and are just loving life in our 400 square foot tiny home.

FAV Master Naturalist Activity or Project: Working the Gault School archeological digs has been one my favorite activities. It combines beautiful scenery, a chance for discovery, a humbling perspective about our brief time on earth, and good old digging in the dirt. Pretty hard to beat!

Of course, now that I’m helping with the HCMN website, I’m happy to put some of my technical skills to use, too.

Bird I most identify with: American Kestrel. As a youth, I was obsessed with birds of prey and falconry, all sparked by these modest but capable “windhovers” that I would watch hunting in fields on my way home from school.

Lance Jones

Lance Jones

Roadrunners - HCMN Class of 2008

About Myself: I served 30 years in the U.S. Coast Guard, one of the best military services, where I worked as a photojournalist. Yes, I went to Alaska but also New England, Florida, and California, and did short stints in Haiti, Cuba, Newfoundland, Canada, Venezuela, Panama, and Brazil. I retired in 2005 and moved to San Marcos to finish my bachelor’s degree in Mass Communications.

You May Not Know: I’m an Air Force brat. My dad was career Air Force, and we lived in bases in Texas, Washington, Nevada, and Illinois. But the best was living for three years in Zweibrücken, Germany, when I was old enough to travel on my own and appreciate it.

FAV Master Naturalist Activity or Project: I love the opportunities we have to see and do so much. The folks we associate with are so smart and willing to share their experiences with others. I work weekly with San Marcos Greenbelt Alliance and the Discovery Center, but I like exploring other volunteer opportunities like the Austin Water Quality Protection Lands along with other Hays County Master Naturalist Chapter opportunities, such as the Training Committee, the new HELM organization, and Outreach.

Bird I most identify with: The Roadrunner. I wish I was that quick. It’s a graceful, colorful bird. But it’s also part of the cuckoo family!

Hays County Master Naturalist Chapter

Online Media Powerhouse

Tom Jones

Shout it out! "The HaysMN Chapter is a Media Powerhouse!" Really…? A small Chapter has online media that bests other Texas Master Naturalist Chapters and even some of our Partner organizations? Yes, it’s true, I will shout it out from the top of Ol' Baldy and off the Devil's Backbone.

HaysMN Herb Smith

First, I want to give credit to the Chapter member with the vision to build our first website 18 years ago. Thank you, Herb Smith! It was Herb who lit the spark of imagination that started the Chapter's online media movement. Herb started work on the Chapter's first Website in 2003. In 2006 he was recognized for designing, producing and maintaining several important birding and nature websites, including Hornsby Bend Bird Observatory, TexBirds, Hays County Master Naturalists, and Wimberley Birding Society. He also created the HaysMN Forum in 2008, which has thrived for the past 13 years.

The HCMN May 2008 Newsletter reported on the creation of the Forum with the following announcement:

"If it hasn't happened by the time you read this, our new HaysMN Forum Google Group will be announced very soon. The Forum is an online discussion group where we can interactively exchange and distribute information among our members. Forum participation is restricted to members and students of the Hays County Chapter of the Texas Master Naturalist program, and is by invitation only, … Better yet, use the Forum to discuss the Forum.” Herb Smith, Webmaster

Our Chapter is a small and dynamic organization. The fact that it has sustained a long term media presence is remarkable. Creating the first website and establishing the Forum required technical skills that were not widely available at the time. Herb and the others who followed him made long term commitments to sustain and build on what they started. These efforts shaped our Chapter and continue full speed today.

Eight of the most popular online media sites are highlighted below. All but the Forum are accessible and viewed by the public. The HaysMN Website and BHC.org are the primary entry points used by the public to learn about the Chapter. The online Hays Humm is viewed in all 50 states and 23 countries. Click on the links below the to learn more about our Online Media Powerhouse.

HaysMN Forum

“The trick to these photos is very simple... find a hummer nest close to the ground ! I used a small 3 step household ladder and a pocket size Canon PowerShot SD600 set for macro, flash and the standard auto focus.” — TD Post, May 2008

By Mike Davis - posted to the Forum

The HaysMN Forum was started by Herb Smith in March 2008. The initial idea came from a HaysMN who suggested a public facing blog style website. After some discussion, we decided on a private mail-list style forum that would allow Hays MNs to ask/answer questions and discuss MN topics knowing that the audience had shared training / interests. It is notable that the original idea was later implemented via our public facing Facebook pages.

In August of 2019, the HaysMNPhoto Forum was added to allow sharing larger photos and short videos. The idea is to allow Hays MNs, with slow or capped internet service, to opt out of these larger posts. I expect the HaysMN and HaysMNPhoto forums to continue much as they have. But we should always be willing to improve them.

I’d like the chapter members to continue to take advantage of these private forums to discuss some of the more difficult issues wildlife face today: habitat loss, climate change, delisting of some threatened species, etc. I have always been pleasantly surprised at the level of participation in both forums, with members sharing detailed nature observations and stunning professional grade photos - TD

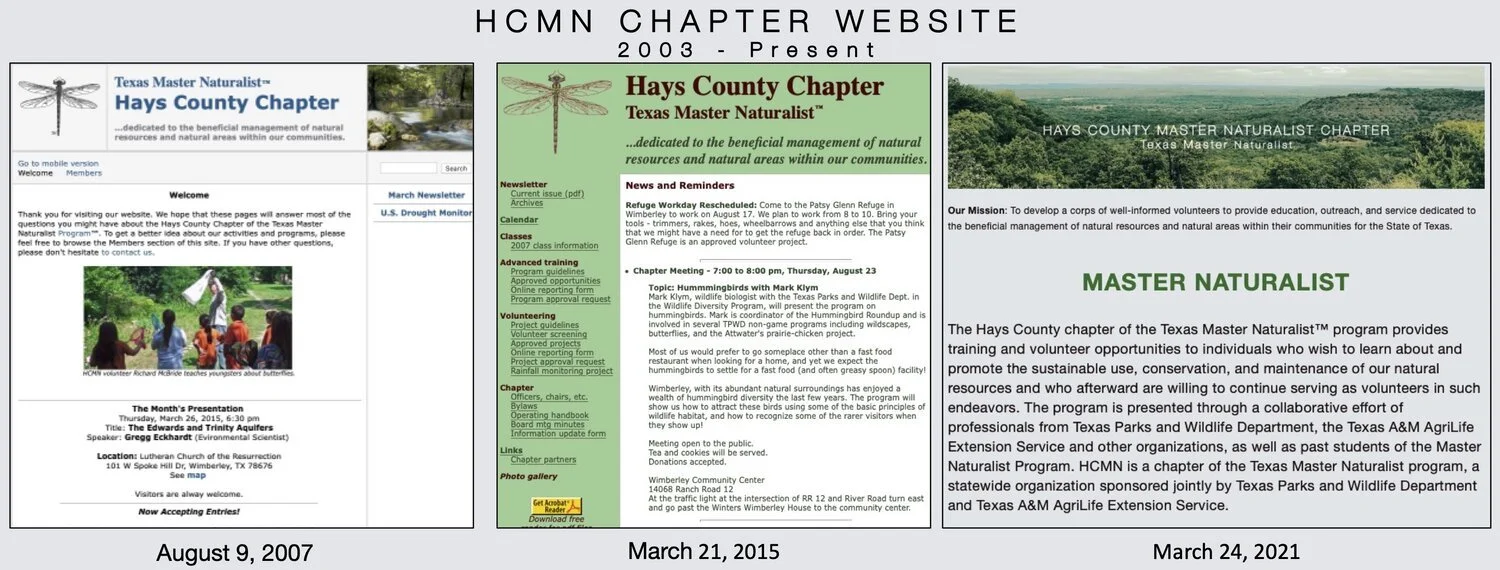

HaysMN Chapter Website

Herb Smith started working on the first Chapter website in 2003, and it was published online shortly thereafter. Herb managed the website for almost 15 years. This was a groundbreaking effort, considering that most TMN Chapters did not have a website until after 2020. I partnered with Betsy Cross to take responsibility for the Chapter Newsletter in 2018, just a couple of months after graduating from the 2017 training class. In the summer of 2018, the Board approved our request to take the Newsletter online. At about the same time, Art Arizpe mentioned that the Chapter website needed an upgrade, and I agreed to create a new one. The timing was perfect. I took the lead to search for a new website vendor and led the effort to build the website from scratch. Having no experience in website design, I quickly learned the basics and created the website using Squarespace. It was released online in September 2018.

Our website has grown and expanded over the years. I am happy to report that Brent Jackson has volunteered to fill the role of Assistant Webmaster. He is already hard at work keeping the site current. Check out Brent’s bio in the Meet Your Master Naturalist feature this month.

Beautiful Hays County Website

"People always admire the site's beautiful photographs. As co-sponsors of the Naturescapes Photography Contest, we have rights to all the entries, and they provided the majority of the photos. I was pleased with the way our members stepped up and wrote the content. This was a big effort, coordinated by Lin Weber, and it provides the public with useful and easily accessible information.” - Art Arizpe

The vision for the beautifulhayscounty.org (bhc.org) website came from the original Willett Foundation grant in September 2014. Their only directive was to increase our chapter's visibility in our community. HCMN Project #1406 was created, and a committee formed to explore ideas on use of the grant funds. In March of 2015, the website and marketing plan received Board approval. Upbeat Marketing was hired to create the website. From March to July 2016, HCMN members were identified to write website content for each of the following major topics.

Water

Wildlife & Insects

Plants & Landscape

Conservation & Restoration

Resources

After an initial rollout of beautifulhayscounty.org in December 2016, it was released to the public in July 2017. Since the initial rollout, additional topics and content have been added. These include:

Riparian Recovery Network News

E-Nature for Kids of all Ages

Habitat-Enhancing Land Management (HELM)

Willett Project Mission - "To ensure Hays County Master Naturalist Chapter is the go-to source of information, guidance and support to help our neighbors in Hays County preserve, restore and enjoy the natural wonders of our area."

The Hays Humm Online Newsletter and Magazine

In 2018, a couple of months after graduating from the 2017 training class, I partnered with Betsy Cross to write and manage the Chapter Newsletter, The Hays Humm. After publishing the Newsletter in a PDF format for several months, we decided to move it online. We loved the idea of creating a Newsletter as a webpage, although neither of us had any idea how to do this. The first online edition of The Hays Humm was released in October 2018. Moving from a PDF document to the web was a good decision. It allowed us to create strong visuals using high resolution photographs and videos that create anticipation and interest. Each month is a new edition featuring stories that foster a sense of connection, while real time reporting on projects inspires participation. Member submission of stories, photographs, and video bring the Chapter to life. We curate the content to ensure maximum impact to the reader.

From the beginning, it was much more that a two-person job. Growing the team requires additional coordination and organization. The learning curve to create, manage, and update the online Newsletter is greater, but we expected that.

Sustainability is another important consideration. Back-up and succession planning demand the recruitment and training of new team members with expanded skills and technical expertise. It’s a monthly commitment, and the hours add up, which is another reason to grow the team and share the work. We have a website link for members to send us their spontaneous content. These submissions add to content diversity, provide volunteer hours for our members, spread the work, and help to spawn new ideas.

Hays County Master Naturalists Facebook Page

E-Nature for Kids Facebook Page

Christine Middleton - In terms of E-Nature, I am often inspired by discussions I see on our MN Google (Forum) site that I think should be shared with a wider audience. I’ve also learned our group includes some great nature photographers willing to share their images with the wider world, and there are several who I often go to for images, primarily Betsy Cross, Eva Frost, and Mike Davis. I’d love to have more people like Tina Adkins recently, who let me know she had captured an interesting image. I’d love to encourage more MNs to send me photos and additional information on things they think could be turned into interesting posts. In terms of research, I often use Google to educate myself on a topic and find interesting tidbits to share. I find Texas Parks and Wildlife websites as well as Audubon, Cornell Labs, and other reputable sources especially helpful.

I’m hoping your article will encourage more among the general membership to think about sharing information with the wider community, not just among ourselves. Now is a good time to increase awareness, and online media is a good way to raise awareness of nature and what we do to protect it.

YouTube Channel

The Chapter’s YouTube channel was created in late 2020. It was Chris Middleton’s idea to make the channel. Dick McBride had been making videos for Chris Middleton to post to her E-Nature series on the "Beautiful Hays County” website. She felt that the videos often didn’t play well and wondered if they might play better over YouTube.

“It was new experience, but it wasn’t too hard to set up a YouTube channel and transfer many of my videos to it. I made a few of David Womer’s Nature Watches into short videos on various subjects that Mary O’Hara has been showing to the training class on off Tuesdays.”- Dick McBride

iNaturalist

iNaturalist is a social network of naturalists, citizen scientists, and biologists built on the concept of mapping and sharing observations of biodiversity across the globe. iNaturalist may be accessed via its website or from its mobile applications.

“The use of apps for collecting natural history data has greatly expanded in recent years with two platforms, iNaturalist and eBird, becoming widely accepted and utilized by conservation agencies and organizations across the country and globe, including the Texas Master Naturalist Program and its sponsors, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service.”

Mary Pearl Meuth,

Texas Master Naturalist Program Assistant State Coordinator

“I think COVID has created a larger spotlight on, and forced us to learn, its power to connect our chapter and its mission to a larger audience. I first created an iNat Project in the summer of 2019 to move the Water Quality Protection Lands’ seed monitoring project. My use of iNat was to help with my IDs before sending in my seed ripeness reports to the Austin Wildlands staff. iNat offers several benefits, including:

Supporting GPS locations for the ripeness monitoring (so staff or volunteers can find the plants later),

Adding supplemental information, such as how many plants are at the observation, and

Easier sorting/analysis of the data collected.” —Bruce Cannon

Link to iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org

Want to get started using iNaturalist? click this Link.

Red-shouldered Hawk — A Lesson in Aerodynamics

Betsy Cross

I often hear the distinctive call of a Red-shouldered Hawk while checking the bird boxes at Jacob’s Well. With a wingspan of 37.0-43.7 inches, Buteo lineatus is one of our more common forest raptors in Hays County. But this was my first time to photograph one on the Jacob’s Well property.

I noticed the hawk on the ground in the tall grass just before it flew up to perch on a power line. I clicked a couple of photos while it studied the landscape below. And then the bird made a sudden dive to the ground again.

Red-shouldered Hawks eat mostly small mammals, lizards, snakes, and amphibians https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Red-shouldered_Hawk/overview . But apparently this dive bomber missed its target, and within a few seconds it turned into a stealth bomber and returned to the woods empty-handed—or should I say “empty-taloned?”

Chapter News

Mother Earth Podcast - Produced and hosted by Salwa Khan, edited by Bob Currie

Listen to the Podcast: http://mothering-earth.com/

Mothering Earth is a radio program and podcast about living sustainably and well while taking care of the natural environment. The program is hosted by Dr. Salwa Khan, whose career includes over three decades as a journalist and more recently as a journalism professor at Texas State University. She has been producing the program for the past six years with technical assistance from her husband, Bob Currie, a member of the Hays County chapter of the Texas Master Naturalists whose professional career included working on national news and documentary television shows.

Mothering Earth covers a broad range of stories — from issues like protecting watersheds in the Texas Hill Country to efforts to rid the oceans ever-accumulating pollution from plastic waste. Many of the shows have interviewed members of Master Naturalists as well as international experts and news-makers. According to Dr. Khan, “Listeners meet fascinating people and get practical information you can put to use, right away."

Mothering Earth can be heard every Sunday at 11am on KWVH Radio in Wimberley and on almost every podcast platform. It is always informative, interesting, fun and almost never preachy.

Thank You Contributors

Tina Adkins, Art Arizpe, Bruce Cannon, Mimi Cavender, Art Crowe, Bob Currie and Salwa Khan, Brent Jackson, Lance Jones, Dick McBride, Christine Middleton, Constance Quigley, Herb Smith, Steve Wilder

HILLS CHILLED NOT KILLED

Mimi Cavender

Six weeks ago, Central Texas was Chill Country—a hauntingly beautiful nightmare. For those of us still mending shattered plumbing, the memory is bitter and slow to fade. The Big Chill of mid-February, 2021, will be one of those stories our grandchildren will have to sit through. You can revisit that deep frozen week through the eyes of Hays County Master Naturalists in the March issue of this Magazine.

You remember that as our plumbing burst, tree limbs split, and our agaves froze to mush, we early walked out on properties large and small and tried to assess the damage. Panic set in. Would all those cacti and agaves survive? Redbuds bloom? Buckeye buds open? Would our precious red oaks really green up again from under all that crispy dead foliage? Would our iconic live oaks recover?—on ice for a week, they thawed out golden brown or slate grey and were bare after another two weeks of eerily heavy leaf fall. Even the mountain laurels were browning, though slower to show it. And would the wildflowers bloom? Toto, I don’t think we’re in Texas anymore!

March came in like a lion, and we’ve been yo-yoing between spring and weird little cold fronts. Panic needs calming, questions need answers. And like spring, answers are beginning to come. We know our bird populations did just fine. Pine Siskins are gone (one way or another), and Whoopers and Sand Cranes are kettling overhead. The Monarchs are here! (Betsy Cross has some news on them in this issue.)

Depending on the ecosystem in our personal patch of Texas, we’re seeing variations in freeze recovery south of the Balcones Escarpment, over in Buda, out in hilly western Hays, and up in Dripping Springs. Some of us have Bluebonnets! The folks at AgriLife reassure us that this spring’s Wildflower Season will be a good one. Little mercies.

Though not technically the Master Naturalist’s purview, many non-native garden plants were devastated. C’mon, we all cheat a little, so we and our gardening friends shed tears together over freeze-blasted landscaping favorites: rosemary, the salvias, lantanas, sago, elaeagnus, vitex, Monterrey oak, oleander, and huge stands of yellow primrose jasmine. The most frequently asked question across Texas since the Big Thaw—second only to Djever get a plumber?—has been Think it’ll come back from the roots?

So as the weeks pass and Texas greens, one reassuring truth begins to emerge: if a species is native to Texas, it has frozen before over eons and has long ago adapted. Yes, it’s all greening as we read this. Let’s walk along a rural road near Wimberley, a fair cross section of Hays County, and look for signs of spring. We’re keeping a photo nature journal.

Only six weeks ago this little woods sheltered starving deer, and every leaf and limb was heavy with ice. One of those low juniper limbs shattered under the weight. Don’t rake and bag the tons of fallen oak leaves; they’ll hold soil on the slope and gradually build layers of nutritious humus to amend our garden soil.

We all watched native prickly pear emerge perky from the ice, but now we’re noticing damage: lots of very dead pads and white, splotchy survivors. Agaves were a mixed bag; some came roaring back, but some rotted and broke away putrid from their core. Luckily they’re all sprouting pups from rhizomes.

Browned out live oaks, so scary bare just last week, are already dusting pollen in San Marcos. Their delicate buds are subtle magic, hazing the canopies green.

All the various white oaks, the precious red oaks—even those stubby lichen-encrusted little oaks along the fence lines—are bursting with new life. Cedar elms, Buckeye and Texas Redbud are blooming everywhere.

Photo: Texas Agricultural Experiment Station

There’s confusion about “buckeyes.” Non-Texas native, painted buckeye (Aesculus sylvatica), is a species of short tree. In my photo above, the flowers, bursting out together with the new leaves, will be creamy yellow with a little red. They make a light brown dry egg-shaped fruit with a shiny brown chestnut-like seed inside. The species is drought and freeze hardy if planted here. Red buckeye (Aesculus pavia) is also a true buckeye, but blooms red or dark pink instead of yellow, has similar fruit, is more shrub than tree, and is a Texas native. Confusion sets in when folks call the Red Buckeye a “Mexican Buckeye.”

Our native Mexican buckeye (Ungnadia speciosa), or false buckeye, is not a buckeye! It has a more lush pink bloom recalling that of Eastern redbuds. Texas A&M tells us that Mexican “buckeye” “…occurs mostly west of the Brazos River on well drained limestone soils on stream banks of damp canyons in South, Central and West Texas, east to Dallas County. Its pink flowers bloom simultaneously as it leafs out with light bronze colored leaflets, which turn pale green during the growing season. Its fall color is bright golden yellow…This plant may be used as a large, coarse multi-trunk shrub or trained into a small tree...” It’s not related to the yellow- or red-blooming Aesculus “true” buckeyes. Bottom line, all three are bare in winter but spectacular in spring and fall.

Low-growing Texas natives, now still bare or just budding, are often overlooked in the landscape. Texas persimmon (Diospyros texana Sheele) reaches for the light as a slender understory tree; its smooth grey trunk and limbs curve into free-form sculpture if rutting bucks don’t scar it first. On Blackland, in sunny suburban yards, specimens will spread out on a more substantial trunk, still gently twisting silver grey. Persimmons are semi-evergreen; tiny fragrant cream-white flowers bloom on the female trees (when a male is nearby) and produce 1-inch astringent, black, boot-staining fruits that critters and mockingbirds adore. But in a corner of our property they’re worth the mess. Evergreen sumac proliferates as a large woody shrub unnoticed along fence lines, competing with junipers for light. It forms loosely cascading natural hedges. This hardy native should be stocked in our nurseries and planted for carefree privacy year round. Bonus: it’s dark green all year until a freeze gives us flame-red foliage that browns and drops just before new buds pop.

Speaking of natural hedges, Texas mountain laurel can be planted for exactly that. The natives have shorter, lighter purple bloom panicles but are longer lived than the showier nursery versions. They’re hard to transplant from nature and notoriously slow growing. But they’re genuinely evergreen, growing from short in understory to tall and wide in sun. February’s Big Freeze turned their foliage a scary army green, with leaves browning unevenly from the outside in. But they never completely defoliated and should gradually replace the damage. New buds were frozen solid, so probably no grape Kool-Aid scented blooms this spring. Are you seeing blooms?

Planting for privacy? Considering oleander? Look closer. Ugly half the year. Fast grower, pretty blooms, but prey to freeze, drought, underwatering, overwatering, and the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa that causes untreatable decline. Not a Hill Country native. Just don’t.

Here’s your mystery plant for this issue. In roadside ditches in semi-rural Central Hays, there’s a fascinating little low-spreading evergreen shrub that has unevenly reddened after the Big Freeze. Enlarge and look closely. Barely over 2 feet high and characteristically thorny, with leaves only ¼ inch long, it looks for all the world like a very miniature version of Pyracantha coccinea—the adapted Asian native, now ubiquitous, tumbling over our city walls and ranch fences. It competes with possumhaw (Ilex decidua) and yaupon (Ilex vomitoria) for gorgeous red winter berries. Everything about this little ground creeper resembles standard Pyracantha, but tiny. I’ve never seen it bloom. Any guesses?

Along the road, we notice more sure signs of spring. Little Bluestem clump grass brightened a grey winter, waving its rusty spikes above the snow. It’s greening now around the base for another year of reliable beauty and soil retention. Shaggy Bluestem, Seep Muhly, Curly Mesquite, and so many other beautiful native grasses well worth seeding are doing the same. Here in Wimberley, the Agarita (Mahonia trifoliolata) is just opening its first shy honey-scented flowers. Nurseries should sell these species to help us transform our Texas yards. Ask your local nursery folks if it’s possible to order a wider range of Central Texas native grasses and shrubs. Native American Seed Farm in Johnson City https://www.seedsource.com/catalog/ and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center near Austin https://www.wildflower.org/plants/ are good resources. Texas AgriLife recommends growing hardy native and adapted plant species, by region, with photos and information on Texas persimmon, redbud, mountain laurel, grasses, and more: https://agrilifeextension.tamu.edu/solutions/best-plants-trees-grow-texas-landscapes/

Back home now in our unmown front meadow, we spot our very first Texas Verbena! So far, no Bluebonnets; I forget to seed them every fall---something about scarifying…

And look, just peeping out, so un-Texan timid, are these little Anemones (Anemone berlandieri). They’re sure signs of renewal after our frozen February 2021.

Today an Antheraea Polyphemus moth, a little worse for wear and nearly lifeless, fluttered onto our doorstep. A beautiful owl-eyed male (See the long, comb-like antennae?), he must have survived the freeze still cocooned. Ask Master Naturalist and moth expert Eva Frost. She and I wrote about the life cycle of Texas’ big Polyphemus in last July’s Hay Humm. For a timely take on cycles of survival, revisit Mega-Moth! Although Eva raises the caterpillars, she says she’s rarely seen the moths. After emerging from their cocoon, adults live about three days mating and dying, well camouflaged on trees. This beauty fluttered home to me.

Nature moves in graceful circles, often predictably, sometimes clothed in mystery, always with spring flowers in her hair.

Winter Storm Follow-up

Tina Adkins

As a result of the February ice and snow, a select few plants are either delayed in recovering with no visible spring shoots or were severely damaged requiring modification/trimming. A couple of plants that are delayed include Viburnum obovatum Walter, Ficus carica (fig tree), and Laurus nobles (Bay Laurel). The Bay tree is approximately 12’ tall with a breadth of 10’ and trunk diameter of 10 inches and about 28 years old. The weight of both the ice and snow bent the entire tree almost to the ground for 10 days. It gradually sprang back up without breaking any branches; however, all the leaves are dead despite the bay scent. Here are before and after shots.

Many of our Ashe Junipers took a beating, losing large limbs and necessitating Dr. Chainsaw’s removal. One of our multilimbed juniper trees (branches from the ground up) split eight different limbs. But of course the main trunk survived to carry on. Our 35’ Bald Cypress was covered with ice and snow, yet endured as if the chilling temperatures provided only a brief challenge, perhaps because the lacy needles were very fine and already brown. Even though the snowpocalypse was very rare, the majority of our native plants are bursting forth with new sprigs, leaves, and blooms. Spring in all its amazing glory has triumphed!

I have to admit that the reason I read this book is that I am a member of the 2016 Master Naturalist class: The Ravens. But what I found from reading this New York Times Book Review “Notable Book” is that we picked well.

Ravens are engaging creatures with a complex interaction among themselves and with their environment. Ravens share information among other ravens about food sources, a system that in the long run is mutually beneficial for all. The one thing they do not share is their nesting territory. Breeding in ravens is reserved for a select few. There is, therefore, a large number of juvenile ravens just out looking for fun while waiting for a territory to open up. We learn ravens are playful. They have been observed sliding down snowbanks on their backs. They have been seen swinging from telephone wires by their beaks.

Heinrich becomes a “raven father” by adopting young ravens and providing them a roosting and feeding area while he is able to observe their behavior out of sight. His carefully designed experiments both in the wild and in his enclosure lead to conclusions that are based in sound, scientific behavioral ecology.

He is not afraid to delve into the complex mythology that surrounds ravens, however. My favorite is the Norse myth of Odin, the father of all humans and gods. In human form, he was somewhat imperfect in that he only had one eye and therefore lacked depth perception. This was made worse because he only drank wine and only spoke in verse. In addition, he was uninformed and forgetful. But his ravens: Hugin (mind) and Munin (memory) were his salvation. They perched on his shoulder and told him of their flights to the ends of the earth. He also had two wolves who were his constant companions and providers of food. As in many myths, there are hidden, profound truths.

Heinrich writes convincingly about this man-wolf-raven association as a necessary survival technique for early northern peoples. Picture the man-raven-wolf interaction: A hungry or starving raven, who knows that the proximity of human hunters with caribou means a meal, would likely have felt exuberant on seeing human hunters when caribou were grazing nearby. Knowing that caribou were potential food, it might have learned that caribou in combination with humans is food. And might wolf kills of caribou seen by ravens have notified humans of potential food? This then becomes an interspecies sharing of information that is once again mutually beneficial for all. That interaction led to a reverence for ravens amongst the Norse. Interestingly enough, when humans shifted from a hunter-gatherer existence to an agricultural one, the raven changed from being an advisor to the gods to just a plain-old-pest. Heinrich brings us back to the present day and how naturalists are trying to bring ravens back to parts of their native ranges here in the USA and in Europe.

SPRING FLURRY

Betsy Cross

![Mexican [false] buckeye in full spring riot.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6216ab102ecdc542ce194387/1648147570336-YE4G2H35LDQI8KR5XHE8/12_mimi_row%2B5.jpeg)

![Painted [true] buckeye, a hardy non-native, blooms creamy yellow.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6216ab102ecdc542ce194387/1648147568825-D1U3PK9XQVYZNTI7H0YZ/11a-mimi_row%2B4.jpeg)