The Hays Humm - May 2021

The Hays Humm

Award Winning Online Magazine - May 2021

Tom Jones - Betsy Cross - Constance Quigley - Mimi Cavender - Steve Wilder

iNaturalist and Making Your Place “A Place”

Steve Wilder

One of the highlights of my class studies in the HCMN program was being introduced to iNaturalist. Many of you are already familiar with the program, but it was all new to me. iNaturalist is a joint initiative of the California Academy of Sciences and the National Geographic Society. It is a social network of naturalists, citizen scientists, and biologists built on the concept of mapping and sharing observations of biodiversity across the globe. iNaturalist provides a place to record and organize nature findings, meet other nature enthusiasts, and learn about the natural world. It encourages the participation of a wide variety of nature enthusiasts, including, but not exclusive to, hikers, hunters, birders, beach combers, mushroom foragers, park rangers, ecologists, and fishermen. Through connecting these different perceptions and expertise of the natural world, iNaturalist hopes to create extensive community awareness of local biodiversity and promote further exploration of local environments. As of February 2021, iNaturalist users had contributed approximately 66 million observations of plants, animals, fungi, and other organisms worldwide. The primary goal is to connect people to nature, and the secondary goal is to generate scientifically valuable biodiversity data from these personal encounters.

iNaturalist is like having an entire library of field guides on your phone. You can simply shoot a picture of a plant, bird, or animal that you encounter, and iNaturalist will help you identify it. You can even use pictures you’ve taken in the past and learn just what that beautiful bit of nature you experienced is. iNaturalist may be accessed via its website or from its mobile applications.

Getting Started

Technologically, I admit I am challenged. I can successfully turn on a computer 3 out of 5 tries. But iNaturalist is so user friendly anyone can use it. Just in case anyone is as challenged as I am, here are simple steps.

For the phone app, just go to wherever you normally get apps, and download iNaturalist for free. On your PC or laptop, search for iNaturalist.org. When you have downloaded it, you’ll need to set up your account. iNaturalist is very user friendly. Just follow the simple steps on the app, select your username and password, and voilà! You’re ready to go.

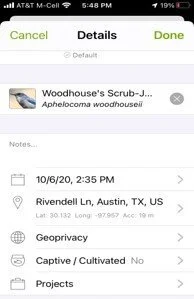

Once you’re signed in, you’ll see your Observation screen. Time to make your first observation. Just tap on Observe in the menu across the bottom of the screen, and you get a pop-up menu with choices of No Photo, Camera, or Camera Roll. If you’re observing something new, choose camera and take a photo. If you think the photo is clear enough, select “Use Photo” at the bottom of the screen, or choose “Retake.” Once you have selected “Use photo,” you’ll be taken to a “Details” screen, shown below.

If you want to add photos of the plant or animal to show additional detail for identification, simply press on the plus sign in the square next to your photo. Once your photo detail is satisfactory, press “what did you see,” and iNaturalist will search its database for similar observations and give you the 10 most logical identifications. You can select one, or type in a name if you desire. Just below the “what did you see” bar is an area for “notes” if you’d like to add any detail for the observation. Next, the calendar icon represents the date and time of the observation, and below that, the location. If your phone settings are open for date/time and location, these will be filled automatically. If not, you can enter manually. The geoprivacy bar allows you to select your privacy level. At the next bar, you can select if the organism is one that is Captive or Cultivated, or if it is occurring naturally, just select No. (Note – for an observation to be classified as verifiable or research grade, it must not be cultivated or introduced by humans.) The last bar is “Projects,” where you can select to add your observations to specific collections or projects that are appropriate to your area or group.

Once you have made all your selections, you simply press “Share,” and your observation is added to the iNaturalist database. The observation will then be graded by Data Quality Assessment. The Data Quality Assessment is a summary of an observation's accuracy, completeness, and suitability for sharing with data partners. The building block of iNaturalist is the verifiable observation. A verifiable observation is an observation that:

has a date

is Georeferenced (i.e. has latitude/longitude coordinates)

has photos or sounds

isn’t of a captive or cultivated organism

Verifiable observations are labeled "Needs ID" until they either attain Research Grade status or are voted to Casual via the Data Quality Assessment. Observations become Research Grade when the community agrees on species-level ID or lower, i.e., when more than 2/3 of identifiers agree on a taxon. Here’s a link for more detailed information on how to use iNaturalist:https://www.inaturalist.org/pages/getting+started#how_ident_work

Making Your Place “A Place”

A lot of us in Hays County have the good fortune to be in more natural environments and have enjoyed observing plants and animals through their life cycles and through the seasons. One way to look at your property is to think of it as a “neighborhood,” and all of the flora and fauna as “neighbors.” All the life around you becomes animate, and you can develop a personal relationship with the organisms that you’ve never really been introduced to. That’s where iNaturalist comes in.

Some Favorite Observations

White-tailed Deer Odocoileus virginianus

When you begin to make observations, you make acquaintances with all your living “neighbors,” and you begin to have a better understanding of your property, its place in your local geography and ecosystem, and how your “neighborhood” functions as a complex and beautiful set of interrelationships. When you have 50 “verifiable” observations, your property can become a “place” and potentially contribute even more to citizen science. Making observations that are detailed enough to earn “Research Grade” status can help catalog populations, determine migration activity, identify changes in the ranges of species, and track species that may need protected status. Perhaps you’ll even find something rare.

Making your place A Place by making 50 verifiable observations is easier than you think. Start with the life forms that are most familiar to you. A lot of us are birders and have taken pictures of them on our feeders and birdbaths. Beginning with them, you can move to your native wildlife—deer, squirrels, foxes, skunks, raccoons…a ringtail if you’re lucky. Then your trees—your oaks, “cedars” (Ashe juniper), hackberry, cedar elms, persimmons—whatever grows naturally on your property. Move on to the shrubs—mountain laurel, yaupon holly, cenizo, agarita, sotols, and yuccas. Blooming native flowers like bluebonnets, verbena, anemones, brazos rain lilies, and goldeneyes are all common to our area. And don’t forget grasses. The more you learn and understand grasses, the more you can understand about the history and health of your property. And of course, the bonanza of them all, insects and spiders. There are a million of them: moths, butterflies, beetles, ants, cicadas, and so many more.

To make your place “a place,” you’ll need to sign into your account on a PC or laptop. Once you have reached 50 verifiable observations, start by clicking on Places under More in the header. You’ll be taken to a map of the world, with sample locations on it. At the upper right, you’ll see a search box called “Find a place.” Leave the box blank and select the blue “Search” button. In the same upper right quadrant, you’ll see “Not finding what you want? Add a place.”

Create a New Place

Click Manually “Create a new place.”

Enter the name of your place.

If the place falls completely within some other existing iNaturalist place, like a state or county, add that place as the parent.

Draw the boundary of your place manually

…or upload the boundary as a KML file.

Select the place type; for parks, select “Open space.”

Save your place.

Once you have created your place, continue to document as many living forms as you can. As you begin to get into “knowing your neighbors,” you begin to see the incredible biodiversity even in small plots and the delicate interrelationships between them that keep the ecosystem healthy.

Besides the satisfaction of having your home be “a place,” one of the advantages is the ability to host a “bioblitz” on your property. A bioblitz is a community citizen-science effort to record as many species within a designated location and time period as possible. Bioblitzes are great ways to engage the public to connect to their environment while generating useful data for science and conservation. They are also an excuse for naturalists, scientists, and curious members of the public to meet in person in the great outdoors; and they’re a lot of fun! Using iNaturalist for your bioblitz encourages public participation and creates high quality data. The app will automatically create a species count for your bioblitz and provides many tools for visualizing and communicating bioblitz results to participants and onlookers. More about bioblitzes and how to organize one can be found at: https://www.inaturalist.org/pages/bioblitz+guide

Making your place “A place” isn’t necessarily for everyone, but iNaturalist is. You can begin to make observations wherever you go, connecting you to the larger world of nature. It’s a great tool for nature journaling; iNaturalist will automatically create your life list, a list of all the species (taxa) you have observed. You can make your own lists of favorite animal groups. It’s a versatile tool to help you understand the world around you. You can even earn volunteer hours when you contribute observations to HCMN approved projects, like TPWD’s Texas Nature Trackers. And it’s all FREE. So open your iNaturalist account and begin to know the incredible richness of your neighborhood!

photo by Larry Calvert

I preface my article by saying that Lone Man and Smith Creeks flow through privately held land. I give thanks and respect to the landowners who granted access to these creeks and allowed me to share the photographs included in this article. My intent is to give the reader a look at two beautiful creeks that you may never see.

I spent many summers hanging out on the wonderful Texas Hill Country rivers. I especially enjoyed floating down the Rio Frio, studying the geology as it slowly passed my tube. Spending time on the river allowed me to discover the beautiful creeks that keep the rivers alive. Closer to home, I am always drawn to the lovely landscape shaped by Cypress Creek as it makes its way to the Blanco River in downtown Wimberley.

Lone Man Creek is one of the many small creeks located east of downtown Wimberley. It’s much shorter in length and has lower water flow than the iconic Cypress Creek. However, its beauty and geologic story are impressive. You can get a quick peek of the creek as you drive over it on Highway 3237. Let's take a look at how this small watershed works.

Low water dam along Lone Man Creek.

Note the low flow rate spilling over the top of the dam. The springs on Lone Man Creek have low but consistent flow. Drought conditions this year have reduced spring flow.

Fractures crossing Lone Man Creek

Two parallel cracks run from left to right near the middle of the photograph. Their orientation northeast by southwest indicate that they are associated with the Balcones fault zone.

Pool behind low water dam

The large number of low water dams along Lone Man Creek create multiple pools similar to this one holding water for swimming and the riparian areas.

The Lone Man Creek watershed extends south from Lone Man Mountain and discharges into the Blanco River 5.5 miles south of Highway 3237. Multiple springs provide water to the creek both north and south of Highway 3237. The springs are fed by water from the Cow Creek Aquifer about 100 feet below the surface moving through cracks (fractures) in the limestone. The individual spring flow is quite low, but the high number of springs discharge enough water to maintain creek flow year round, except during droughts.

Lone Man & Smith Creek Map

Creeks and rivers align along faults and fractures, giving symmetry to the Wimberley Valley topography.

Smith Creek

Smith Creek is a small tributary of Lone Man Creek, running parallel to Highway 3237. A spring is located just south of the highway creating a large pool. The photo includes evidence of small karst caverns in the lower part of the cliff, indicating the spring may be karst related. Smith Creek intersects Lone Man Creek, contributing significant flow to lower Lone Man Creek.

Sinya Glamping Resort on Lone Man Creek

Sinya website link: “Glamping,” short for glamorous camping, has become a mainstay of outdoor recreation over the past decade. Photo from Sinya website.

Cliff adjacent to Lone Man Creek

This rock wall is typically referred to as a “cut bank” being eroded by the creek. Note the many layers of thin limestone beds, typical of the upper Glen Rose formation.

Lone Man Creek enters into the Blanco River

Like most creeks in the Blanco River watershed, Lone Man Creek does not contribute significant water flow to the river.

During flood events, Lone Man Creek offers some impressive views of fast moving water, just don’t get too close. During the 2015 flood, rainfall rushed down the creek creating a flood. However, the small size of this creek’s watershed limits a flood’s duration as the creek quickly drains into the Blanco River. Check out the videos below of the 2015 flooding.

I am always amazed at how many springs there are in the Wimberley Valley and San Marcos. I don’t know the number, but it’s too many to count. As summer approaches, I dust off my tubes and noodles in anticipation of cooling off in Cypress Creek. Or perhaps booking the tent at Sinya and taking a dip in Lone Man Creek. I can float on my noodle and stare at the rocks as time passes by.

Mimi Cavender

Down your collar, in your hair, hanging twisting in the air, draping trees like Halloween, the worst invasion ever seen of something neither web nor worm, but caterpillars—watch ‘em squirm! Come sing this little song with me: our spring was not supposed to be like this! Nature froze, and thawed, and sprouted green and optimistic. Then dangling from silken threads, the writhing started overhead, one inchworm crawling up a post, then hundreds drifting through the oaks, thousands raining fecal grit, fresh new leaves reduced to— Well, you get the gist.

The zoo of larval invaders included two variants of a caterpillar generically termed “oak leaf rollers.” They’re eyelash-size moth larvae that hatched this April from near-microscopic eggs laid a year ago—in May of 2020—on twig tips. They hatched this spring among the tenderest new oak leaves, which they rolled or folded over and sealed with silk. Inside, they began eating, denuding twigs, branches—whole canopies! We see them every year but rarely in such alarming numbers. Two species of natural predator wasp were suppressed by February’s sustained hard freeze; with the reduction of two wasps, look at the ecological impact!

These “oak worms,” and a variety of others, with their rapidly developing instars (a larva’s visible physical change with each molt, sometimes only days apart), were everywhere, the length and breadth of Hays County and, by Texas A&M’s account, from Dallas to the coastal plain. Click on Bastiaan “Bart” M. Drees’ https://agrilifeextension.tamu.edu/library/landscaping/oak-leaf-roller-and-springtime-defoliation-of-live-oak-trees/ He’ll do the science-y heavy lifting. We’re going to admire the worms.

All Hays oak species were attacked, but the most severe defoliation seems to have been on our live oaks. Many of us report some live oak mottes were infested while others a few feet away were only lightly nibbled or not at all. Why? And the crossover munching was mindboggling; in central Hays County, the cats also munched on rose buds, Salvia greggi (but not native red, blue or purple sage), buckeyes, cross vine, and citrus species—anything with buds and delicate, foldable, new leaves.

They seemed to avoid leaves with strong scent; leafy herbs, such as cooking sage, parsley, thyme, peppermint, and oregano, were spared. I hope you looked around your property and journaled—listed all the plants colonized by any of the moth larvae and their instars shown in the photos below. It will be useful documentation. Share your observations and photos with an expert colleague at AgriLife: https://agrilifeextension.tamu.edu/contact/ A spring like this one doesn’t come around very often. Do you remember similar ecological upsets after Central Texas’ big freezes of 1983 and 1989? I remember San Antonio’s dead loquats, English ivy, and Augustine lawns—total kill—but I was too ignorant to notice the ecological effects. A Master Naturalist education opens your eyes. And it’s not all pretty.

Here’s a look at several caterpillar species and their instars in my yard on April 17 and some observed by Hays County Master Naturalists during the same mid-April two-week period.

These on black were stripping one oak motte. Getting that shot was like herding cats. Notice the fierce-looking horned instar, lower right corner. The second collection were all together on one small red climbing rose. In the second photo, that pale larva in the center is like our “mystery cat” near the end of this journal. Is this one pink because she’s full of roses?

Much of the silk trapeze action from trees to ground, where they’ll pupate, was from instars of the spring cankerworm (Paleacrata vernata). They are varied gray/green to yellow/orange and brown striped, have light heads, two pairs of prolegs, and two pairs of hind legs. Like other inchworms, with legs only front and back, they must arch and then rear up on their hind legs to move forward. For more, including their fall cankerworm cousin, see https://texasinsects.tamu.edu/spring-cankerworm/ By the way, look closely at the photo of the yellow cankerworm, second from left. Inside their webbed feeding nest, lower left corner, tiny oak leaf rollers are eating their way out.

They were icky in our hair, left a lot of gritty frass, and did a lot of damage, most of it not permanent. But you have to admit these cankerworm larvae are beautiful to look at up close—almost psychedelic. And by May, most of them will have pupated and emerged as small brown and grey moths fluttering now around your porch light. They mate, lay near-invisible eggs, and die within a week. They had their time in the sun.

Oak leaf rollers weren’t the only caterpillars out there; there were the usual grey inchworms, Genista broom larvae (Uresiphita reversalis) on the mountain laurels, Monarch larvae, bless ‘em, on late-blooming milkweed, and seething masses of webworms on Betsy Cross’ fence. If you can take it, play her video: Wall o’Worms

Here’s your fat green mystery cat. It was gorging on live oaks and resting on porch posts. I couldn’t find it in any of the Texas databases. This stout 1.2” uniformly translucent green (pale blue head), many-legged larva is not to be confused with those eyelash-size, pale green, brown or black-headed, freshly hatched spring oak leaf rollers and other greenish caterpillars. So what is it? After reading Steve’s article in this issue, would you like to try iNaturalist?

As usual, mysteries abound. Many of us noticed early April’s strange absence of birds at our feeders—an actual Silent Spring! Were they molting? Nesting? Tired of humans? I watched a single titmouse carry those long thin grey Genista broom inchworms to his hatchlings. Carnivores and nest feeders could have controlled the caterpillars; trees could have been picked clean but weren’t. During 2021’s Great Worm Attack, where were the mockingbirds, wrens and woodpeckers when we needed them?

And while we waited for those cats to run through all their instars, pupate and go moth on us (to mate and lay eggs for next spring!), we closely watched our oaks for a second leafing out. Yes! At each tiny green nub left by a caterpillar, live oak twigs have slowly been re-sprouting. And in your yard? We were triple-stressed this year, by drought, by freeze, and by caterpillars. But we’re Texans, darn it!

Ever heard the phrase, “The best camera is the one you have with you at the time you need it?” Well, on January 23, I was with fellow birders Lynne Schaffer and Susan Evans for a Christmas Bird Count when I panicked. We stumbled upon a humongous nest, and before our very eyes was the majestic Bald Eagle! OMG—of all days to not have my big girl camera! We were able to observe two adults for a good while, and then we noticed small white fuzzy figures in the nest—two eaglets. Lynne was able to get the shot of the adult with one of the babies (above.)

We made a plan to return soon for some better pictures.

February 25 - photo by Doray Lendacky

Our next trip was two weeks later on February 5. Those small eaglets weren’t so white anymore but still a bit fuzzy. Now we were hooked and vowed to return every two weeks to witness the eaglets’ growth. But Mother Nature would make other plans, and the Snowmageddon of 2021 hit during our next planned visit. We hoped the eaglets would survive the single digit days.

We returned on February 25 with great trepidation. Did the eaglets survive? Would the adults be gone?

We were rewarded with sighting one adult. This adult appeared to be very concerned with our presence. It flew to a nearby branch and sounded a warning cry. And from then on, we didn’t see enough of the eaglets to score any photos, but we knew they had both survived.

Having learned our lesson from our previous visit, when we returned on March 10, we approached in stealth mode to avoid detection from the adults. We assumed they were off hunting.

We crept up and sat next to an Ashe Juniper. The eaglets had quadrupled in size and were now feathered in dark brown suits. It was amazing to see how big they were. Doing some rough math from our first sighting, we figured the eaglets to be about eight weeks old now. Google says they fledge between 10 and 14 weeks. We planned to return once a week until they took flight.

March 10th, Photos by Lynne Schaffer

March 18th, Photos by Doray Lendacky

April 1 - Photo by Doray Lendacky

By March 25, the eaglets were getting braver in testing their wings while in the nest.

And on April 1, the next step for the eaglets: venturing out on a nearby branch and getting the hang of their wings.

Sadly for us, our story ends here as we were not able to capture the eaglets on their initial flight. But what a great opportunity to witness Bald Eagles growing up!

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/new-bald-eagle-population-estimate-usfws/

Meet Your Master Naturalist

Steve Wilder

Steve Wilder

2019 HCMN Class of Coronas de Cristo

About myself: I was temporarily absent from Texas when I was born. Grew up in mostly rural settings. My father was an avid outdoorsman and instilled in me a respect for nature through hunting, fishing, camping, and gardening (he grew up working his father’s farms). After graduating from UT, I worked several jobs around the country, then spent a year travelling and vagabonding through Europe. I returned to Austin for graduate school and began a 40-year career in radio, marketing, and retail. Joined the Master Naturalist class in 2020 to better appreciate my property and to learn how to help my three grandchildren understand, respect, and love Nature.

You May Not Know: I have 2 titanium hips, 4 feet of titanium rods and 20 screws in my back, plus assorted plates, screws, and pins. There is so much metal in me, I mix martinis with gin and WD-40.

Favorite Master Naturalist Activity: Because of Covid, I was not able to participate in many outdoor MN projects, but having been introduced to iNaturalist, I have really enjoyed delving into the amazing biodiversity that exists in my own back yard. And working with the Magazine crew has broadened my perspective of citizen science tremendously.

Favorite Bird: Mockingbird. Tom Wolfe described the endless variation of the mockingbird’s song as “he strews about newness as casually as a god.”

Mimi Cavender

Mimi Cavender

2019 HCMN Class of Coronas de Cristo

About me: My 1950s childhood in San Antonio was all long summers, nights full of stars and—Steve’s favorite—mockingbirds “strewing about newness.” On Sunday drives or road trips out West, our dad taught us how to really know and respect the outdoors. My mother was a joyful Master Gardener dividing irises at 102. A small family ranch along Rio Frio’s towering cypresses was a dream world. So, yes, for all my life I’ve been happiest outdoors. Eventually, after self-indulgent exploring life beyond Texas, an M.A. in linguistics and education from Columbia University, and after my own family and 25 years’ teaching English as a second language, I retired to the Texas Hill Country—what else? Here, with more time and surprising remnants of energy, I can learn together with the generous people of Texas Master Naturalists how to give something of lasting good back to the natural world we love.

Favorite hobby or activity? Life! Everything is so interconnected, it’s hard not to be curious. I’ve hand built a dry creek and added native grasses to this little semi-rural acre for my sons and granddaughter to enjoy. An especially talented team of Master Naturalists let me write for our beautiful Magazine. I want to photograph as well as Betsy Cross. And some fellow former-educator HCMNs are planning a brilliant Covid-free future for Chris Middleton’s nature education outreach, Wild About Nature. Oh, and when Canada lets us back in, I want to hike more trails in the Canadian Rockies! Meanwhile, outdoor volunteer hours are right here at home, for the rest of this precious life!

You may not know that through my two sons’ dad, we have dual citizenship. In the ‘70s and ‘80s we lived between New York and Lisbon. Portugal was a time capsule, its 300 miles of coastline fronting an interior of surprising geographical and cultural diversity—almond groves in the Moorish south, fragrant eucalyptus and pine in the Celtic north’s remote deep granite valleys. The central Alentejo looked like our Hill Country, except those were unbroken miles of cork oaks underplanted with wheat and red poppies. We drove and hiked every inch of it. To see unbridled urban sprawl eat up so much of that natural beauty in my boys’ lifetime makes me super-aware of the danger here, that our great grandchildren will never see what we love now. Our work’s cut out for us, isn’t it?

Talisman animal? Maybe a roadrunner? He gives the impression he’s in a hurry to get somewhere and find something wonderful.

Spiderwort at Prospect Park in San Marcos

Betsy Cross

Thank You Contributors

Mimi Cavender

Sonia Duran

Doray Lendacky

Tracy Mock

John Moore

Constance Quigley

Steve Wilder

“As A Naturalist” Music Video

HaysMNs John Moore and Tracy Mock recorded a parody song/video he wrote about being a naturalist ‘cause…“we know, Nature is cool…” Enjoy.

The iconic desert bighorn sheep, Elephant Mountain Wildlife Management Area.

Sonia Duran is a Wildlife Biologist, member of the Texas Bighorn Society and in the HaysMN Class of 2021.

Helicopter transporting supplies to guzzler project sites at Red Rocks Ranch near Van Horn, Texas.

This March, Texas Bighorn Society members ventured to the Chihuahuan Desert of Far West Texas for the annual TBS Work Project. Traveling from as far as the East Texas Piney Woods, volunteers joined Texas Parks & Wildlife biologists at Red Rocks Ranch near Van Horn to construct three wildlife water guzzlers. Guzzlers are rainwater catchment devices that provide wildlife with a relatively consistent source of water. Across multiple trips, a helicopter delivers supplies and dozens of volunteers to the project sites. The sites are often remote and inaccessible by vehicle. Volunteers dig, cut, weld, push, and bolt the large guzzlers into place.

Although used throughout much of Texas, guzzlers are especially important features in arid environments such as the Trans-Pecos, which may receive as little as 8 to 12 inches of precipitation annually (up to 20 inches at high elevation.) Comparatively, annual precipitation in the Hill Country can be more than double that of the Trans-Pecos, and the Texas coast may get more than four times as much. Although desert wildlife are well adapted to these low precipitation rates, water is crucial to their survival nonetheless.

One of the most iconic inhabitants of the Trans-Pecos is the desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni.) As a result of disease transmission from domestic sheep and underregulated hunting, desert bighorn populations were essentially eradicated in Texas by the early 1960s. In recent decades, extensive efforts have been made to restore their populations, and providing supplemental water plays a key role in these efforts.

Although these guzzlers are constructed in the name of the desert bighorn, all wildlife can benefit from them. Thanks to the dedication of TPWD biologists and the Texas Bighorn Society, the wildlife of the Trans-Pecos can live to drink another day.

Peach blossoms

After the “snowpocalypse” and “wormageddon” of 2021, it was almost miraculous to see flowers in April. I was amazed at the resilience of so many of our native plants and trees. Many awakened at their usual time, and others took two weeks or more to recover and begin their springtime bloom cycle. I was particularly happy to find my anacacho orchid tree had survived the freeze and rewarded me with its sweet-smelling flowers. It is currently blooming (end of April), fully two weeks behind its 2020 blossom date. These signs of spring were particularly welcome this year!!