The Hays Humm - November 2021

The Hays Humm

Award Winning Online Magazine - November 2021

Tom Jones - Betsy Cross - Constance Quigley - Mimi Cavender - Steve Wilder

In New York in 1976, we were reading bedtime stories. My 3-year-old’s favorite was Goodnight Moon. Children’s books then were full of animals, moons, and starry skies. But outside our window overlooking Broadway three blocks south of Columbia University, the only visible patch of sky glowed brown. It was opaque. Anywhere you looked there were no stars, ever. That summer we visited my parents in San Antonio. We took a walk, my chirpy little son and I, his hand in mine, walked just a few suburban blocks, an hour after sunset. The night was moonless, star spangled. It smelled of honeysuckle. He was strangely quiet, and then he began to cry and pull me back toward home. He whispered that he was afraid of the sky—he felt he was falling up into the stars. He’d only seen them five-pointed like paper cutouts in books with pigs and bunnies.

But I knew exactly what he’d felt. In that place, twenty-five summers earlier, while my dad read his Outdoor Life indoors and dreamed of hunting season, my mother, little brother and I lay outside on a plump St. Augustine lawn under many many more of those same stars. Only a few TVs flickered in living rooms up and down the street; my dad wouldn’t get one of “those darned things until they’re perfected. All they show is wrestling.” So when we weren’t playing hide and seek in the dark or chasing swarms of lightning bugs to put in Ball jars beside our bed to fall asleep by (they were dead by morning), we lay out many nights on a quilt on the lawn, listening to frogs and crickets and watching Venus follow the setting sun. Star light, star bright, first star I see tonight; I wish I may, I wish I might, have the wish I make tonight. And we wished, and we loved one another. We watched an enormous rising moon and wondered why it grew smaller as it rose. We told fairy tales and ghost stories and waited for Jupiter and Mars to rise. We talked quietly or not at all. The sky was so dark that the Oooooh! of seeing a “shooting star” was commonplace. The bright edge of the galaxy flowed overhead. If you stared at it long enough, you thought you saw it moving. Then, that wonderful panic—you felt you were falling through a bottomless ocean of stars. Childhood touched infinity.

The world was darker. Corner street lights cast soft puddles of yellow. In 1950 San Antonio had 408,000 people, a tiny airport, a dimly lit downtown, no malls, Walmarts, or large parking lots. Restaurants were run by families. San Antonio had no suburbs beyond Military Highway, along which WWII truck convoys full of khaki still rumbled among the six bases: Lackland, Kelly, Camp Bullis, Randolph, Fort Sam Houston, and Brooks. Ten years later, the two lanes widened into Loop 410. If you built it, they would come, and so you built more. New suburbs immediately incorporated “outside the Loop;” they mingled old oaks, juniper, deer, strip malls, people, and light—lots of light. In 1950 New Braunfels had 12,000 people and a sleepy downtown; San Marcos had the “Teachers’ College” and 10,000; Kyle (888) and Buda (483) each had a water tower and a train platform along one main street. And Austin—in spite of state government and the University—was a tidy little downtown with adjacent tree-covered neighborhoods housing only 132,000 folks. All of Hays County in 1950 recorded just under 17,000, 7,000 of which were scattered out across the ranchland. Hidden in the hills, tiny Wimberley and Dripping Springs weren’t yet incorporated and weren’t counted, but each gave the ranchers their church, cafe, feed store, and filling station.

Before it, too, was widened to become I-35, a two-lane “Austin highway” hugged the Balcones Escarpment and strung those towns out through the night like delicate crystal beads of light on black velvet farmland that smelled of manure. After fried chicken dinner and a long Sunday drive (a family pastime then) we drove home, with the windows down for the breeze, through night lit by starlight beyond our headlights. The moon followed us, smiling. Goodnight, Moon.

Photo: ISS crew, courtesy NASA, 2017

In 1950, if we had had the International Space Station, this view of the United States and part of Mexico and Canada would have looked much darker. The points and clusters of light would have been fewer, dimmer, and yellower (incandescent bulbs). The land masses and even the lakes and oceans would have looked blacker. In this 2017 photo from space, our more carbon-polluted atmosphere reflects back to us and evenly distributes all that white [unhealthy blue] light, lending the earth’s surface a moonlit glow. This light wash—light pollution—makes ground based astronomy almost impossible, confuses migrating animals, disrupts night-day rhythms of all forms of life, and is veiling our view to the universe.

International Space Station challenge: Imagine yourself the astronaut taking this photo. Can you find central Texas’ I-35 corridor curving upward along the Balcones Escarpment? And how can you miss Texas’ two largest cities! Can you find the worst transgressor in the United States in terms of white light per square mile? It’s a small city but shows up as the brightest whitest point of light on the continent. And one more challenge: if you find the I-35 corridor stringing upward from San Antonio to Austin (and eventually to huge Dallas), then—just below it—what in the world is that all that light streaking across south central Texas? Isn’t our central coastal plain mostly farms and ranches? (See if you’re right at the end of this article.)

Photo: ISS crew, courtesy NASA

In the International Space Station, we’re orbiting 254 miles above and to the west of San Antonio (round light cluster, lower center), looking southeast toward the Gulf of Mexico. The I-35 corridor curves along the Balcones escarpment, connecting San Antonio, New Braunfels, San Marcos, Kyle, Buda, and sprawling Austin. There’s some compression of distance as you look south and east ahead of us because of the telephoto lens. And forgive the linear blur of each light point; the ISS is moving from northwest to southeast at 4.76 miles per second! The whiter the light, the more likely it’s from metal halide bulbs in large industrial applications—a sports facility, warehousing, a cement plan, or a refinery. Look at Houston, center of the photo, on the Gulf. Wow!

Many towns and suburbs have converted their lighting to the more efficient sodium lights that glow that soft amber, but they turn ambient colors grey. Ideally, dimmable programmable solar LEDs would give efficiency plus natural color retention, but they’re still expensive. And, as we’ll explore in next month’s issue, white light is blue light, the most harmful to our health. In any of these NASA photos, find the brightest white spots and you’ll find where retrofitting is desirable. Infrastructure budget, anyone? As we get wiser, whatever lighting we develop, we must plan for as little of it as necessary and shield it from escaping into the natural environment.

Of course my 40s-50s childhood world was darker—there were far fewer people, fewer roads, cars, big rigs, houses, stores, warehouses, parking lots, ball fields, planes in the sky... Populated areas were small and lit gently with incandescent bulbs. Life was simpler. With fewer people and less stuff, there was less fear and no need to light blast the night. Night was night. We and all of nature rested in it.

Still with me? I do this creaky old lady “When I was a girl…” thing more often these days. But if you too find yourself nostalgic, remembering a more restful world, including a darker and starrier sky, then the worldwide Dark Sky story is for you. It’s a tale of too much: population, urbanization, and light. And of too little: wisdom, darkness, and a community-shared sense of our place in the natural world.

We are made of stars. Every molecule in our body is from an exploded star. There was energy/mass, expanding space-time, and the recycling of atoms across billions of years in space dust, planetary crust, oceans, and air until life organized and reorganized the carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and minerals into us and every other living thing. When we look up, we see the light of some of those stars. Our ancestors.

EVERYONE CAN TOUCH INFINITY. Go Dark. Go out. Look up.

April’s Lyriad meteor shower— Photo: Bettymaya Foott, courtesy International Dark-Sky Association

If there’s a first step for nature enthusiasts— if there’s one powerful source for all things night sky—it’s the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA). If you’re intrigued, begin by exploring their community, events, and resources at https://www.darksky.org/ Become a member from there or by clicking “Take Action” on the photo below:

In the December issue, we’ll see more of what the several IDA-associated night sky groups are doing; spurred on by the broad-based environmental protection group Hill Country Alliance, these night sky groups’ memberships are exploding, and their events are everywhere—keep up! An important local organization closely networked with IDA is Hays County Friends of the Night Sky. Hays County Master Naturalist Cindy Luongo-Cassidy organized Friends of the Night Sky, and she’s a powerhouse. Read more about Cassidy’s work in The Hays Humm March 2020. Meanwhile, there’s a summary just ahead here in this issue of Cindy’s presentation at the Texas Master Naturalist 2021 Annual Meeting, October 21-24. It’s a must-read.

THIS MONTH! Join the International Dark-Sky Association’s 2021 International Conference, UNDER ONE SKY, a 24-hour virtual event. “You’ll hear experts and storytellers in the dark sky movement, connect with passionate individuals from IDA’s global network, and learn about hands-on activities and tools that you can use to protect the night through engagement workshops.” Hays County Master Naturalist and Texas Dark-Sky chapter Director Cindy Luongo-Cassidy will lead one of the workshops. See the complete schedule and register here for this FREE online event.

Lights Out Texas and similar initiatives are doing critical public education. And you can help. Did you know that 1 out of every 4 birds migrating through the U.S. in the fall passes through Texas? Most of them travel at night. Bright lights of commercial and residential buildings attract and disorient birds, causing collisions that kill them or leave them stunned and vulnerable to threats on the ground. Here’s how you can help: turn out non-essential lights, outside and inside, from 11 pm to 6 am during fall migration season, August 15—November 30. With the simple flip of a switch tonight, each of us can easily do our part to protect 3-4 million migrating birds soaring across our Lone Star skies. Learn more about Lights Out Texas

Celebrate your commitment to conservation and encourage others to do the same with a Texas Conservation Alliance Lights Out for Wildlife certification. Every person and every business, school, hotel, home, high rise, restaurant, municipal building, and place of worship can receive this certification–and it’s free to certify! To certify your home, business, or building, visit TCATexas

Space Station challenge ANSWERS: Yep, the small city with the continent’s brightest light bouncing off the atmosphere is—Las Vegas! Figures. And what in the world is that swathe of light across south central Texas where there were farms and ranches? It’s still farms and ranches, but it’s also thousands of oil and gas wells—many of them fracked—across seven Texas counties. Bright lights keep the trucks moving and the rigs staffed 24-7. That view from space is from 2017; here’s the oil and gas industry’s 2021 report.

West Texas, planet Venus after sunset. Original of this photo is by Kim Collins

Coming to you in this magazine’s December issue: Why, exactly, is light pollution so bad? And when we get wise, what can we do? There’s public awareness to be raised, education to be done, legislation to be passed and some regulations applied before we have back our birthright: skies dark and starry enough for us to see life’s origins and put our own species in perspective. Nights dark enough for all species’ good health. Good sleep. Good night sky.

J Drew Lanham, PhD—American author, poet, and wildlife biologist—delivered Friday’s keynote address during lunch to ~215 onsite attendees and 475 online.

SHARING OUR WEALTH

Reported by Mimi Cavender

Three Hays County Chapter members were presenters at the Texas Master Naturalist™ Annual Meeting, October 21-24, 2021, in Dallas, Texas. The meeting was a hybrid event.

What is a hybrid event? Participants could register online to attend the event as either an in person attendee or a virtual attendee. Certain aspects of the event were made available for each audience type; for example, for field sessions hosted for in-person attendees, all relevant health and safety protocols were followed. Virtual attendees participated in advanced training sessions—presentations— that were available for streaming. All virtual aspects of the meeting were also available for “in person” attendees. All sessions were recorded for viewing on the website for ninety days following the Meeting.

Our Hays County Master Naturalist presenters, in session schedule order, were Cindy Luongo-Cassidy, Tom Jones, and Betsy Cross. Adapted from their program notes, here are their presentations in review.

HCMN Cindy Luongo-Cassidy

Cindy Luongo-Cassidy is the Texas Chapter Director of the International Dark-Sky Association. She is a founding member of the Hill Country Alliance Night Sky Team, President of the Board for the Hays County Friends of the Night Sky, and a Hays County Master Naturalist. She was the key player in positioning the City of Dripping Springs to receive designation as an International Dark Sky Community, the first in Texas; she has assisted with numerous other International Dark Sky Place applications in Texas. In 2019 she was awarded the Crawford-Hunter Award, the highest honor that the International Dark-Sky Association bestows to individuals who in the course of their lifetime have contributed extraordinary effort to light pollution abatement. Cassidy lives in Driftwood, and was the creator of the Texas Night Sky Festival®.

Friends of the Night Sky Youth Outreach: Fight for the Stars: Be a Knight for the Night

Want to help youth in your community know why and how to reduce light pollution? Want a truly engaging program that you can lead or share with teachers in your community? We did! And we saw real-life videos of the Fight for the Stars: Be a Knight for the Night program being used in a youth day camp.

The program was created by teen Emma Schmidt for her Girl Scout Gold Award project, and this is brilliant stuff. The package has high-quality youth-to-youth peer-taught videos and downloadable activity sheets about light pollution for you to learn from (or teach others), all included in a complete curriculum with standards alignments! Level One (for elementary students) and Level Two (for secondary students and adults) use age-appropriate vocabulary and concepts and have scads of handouts and take-home family learning activities. Both levels culminate in The Globe at Night Citizen Science projects.

Participants prepare a lighting inventory and assessment, retrofit plan, and cost analysis for their culminating activity that earns them certificates, stickers, and Dark Sky patches. Everything is thoughtfully sequenced and attractively packaged; a teacher/leader never has to plan, make, or buy a thing! Except maybe those cool light spectrum glasses?

Lessons may be self-led or led by a teacher, volunteer, family member or friend. Be that friend. With young people you love and who will be our world’s future—fight for the stars!

Tom Jones holds a BS degree in Geological Sciences from the University of Texas and completed a professional career as a consulting geologist/hydrogeologist and project manager with General Electric. His work experience includes environmental assessments, impact studies, and Federal/State regulatory support for corporate clients. Tom’s work includes environmental impact studies in the Amazon rainforest, Russia, and the Caribbean. Throughout his career, Tom was committed to community volunteer work, with a passion for the Texas Hill Country. Tom certified as a Hays County Master Naturalist in 2017. He holds Board positions as the Chapter's webmaster and co-editor of the Chapter Magazine, The Hays Humm, which has won numerous awards from Texas Master Naturalist™.

Karst—The Role of Water in Shaping the Texas Hill Country

The Texas Hill Country is a destination for many visitors and residents attracted by the numerous hills, deep valleys, and multiple water features throughout the area. Karst is a topography or terrain formed by rainfall entering and dissolving the abundant limestone formations. Common features of karst terrain include sinkholes and caves, which create pathways to the subsurface aquifers. It also forms vast underground drainage systems within the aquifers, which allow ground water to easily enter and move through the rock layers. Karst features are abundant in the Texas Hill Country. Tom highlighted a region of Hays County about 25 miles northwest of San Marcos. Wimberley Valley is home to a wide variety of karst-related features, including many iconic springs and water attractions. Karst influences land use and water resources. Potential impacts include sinkhole collapse, increased risk of groundwater contamination, and an unpredictable water supply. Karst gives this region its iconic Hill Country look and enables the numerous creeks and springs that attract people to the Texas Hill Country.

Betsy’s photo Autumn Stunner was awarded 3rd place in the 2021 TMN Annual Photo, Art & Media Contest—Insect Category

Betsy Cross loves using photography to document nature observations. She tries to capture the living ecology of a region—birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, plants, butterflies, bees, and pollinators of all kinds. She has a particular affinity for observing birds and catching their unique behaviors in motion. Betsy makes it her practice to photograph as many species as she can on her own property in San Marcos. As co-editor of the Hays Humm, Betsy curates and contributes articles and photos for the monthly online magazine of the Hays County Master Naturalist chapter. Betsy is among many bird enthusiasts, photographers, and citizen scientists who every year monitor bird boxes and other nesting habitats to get an intimate glimpse into the secret lives of birds. She shared some of her spectacular results with 2021 State Meeting attendees.

Journey Into Field Photography—The Art and Science of Nesting Birds

Part 1 utilized high quality field photographs taken over the past four years to cover the basics of nest box monitoring along with species-specific behaviors, nest construction, eggs, young, and fledging. Betsy showed how photography is a key element of her documentation and how it has improved her field observation skills.

Part 2 focused on photographic case histories of different species of birds utilizing woodpecker holes for nesting. It emphasized the importance of leaving tree snags in place and showed the nest cycles supported by one dead tree over several years as habitat for a variety of cavity-nesting birds.

Part 3 took a deep dive into the nesting habits of Black-chinned Hummingbirds. If you’ve never seen an active hummingbird nest, watched a mother hummer building her nest or feeding babies, or observed newly fledged hummingbirds in training, you’d have enjoyed this presentation. Using video recordings and photographs from Betsy’s own yard, Part 3 revealed successes, failures, and challenges of nesting hummers. She shared how to spot an active nest and demonstrated her techniques for capturing these resilient little birds in action so that we too might be able to find, observe, and document nesting hummers in our yards.

Betsy’s photo Fledge Day was awarded 1st place in the 2021 TMN Annual Photo, Art & Media Contest—Bird Category

And at your request…

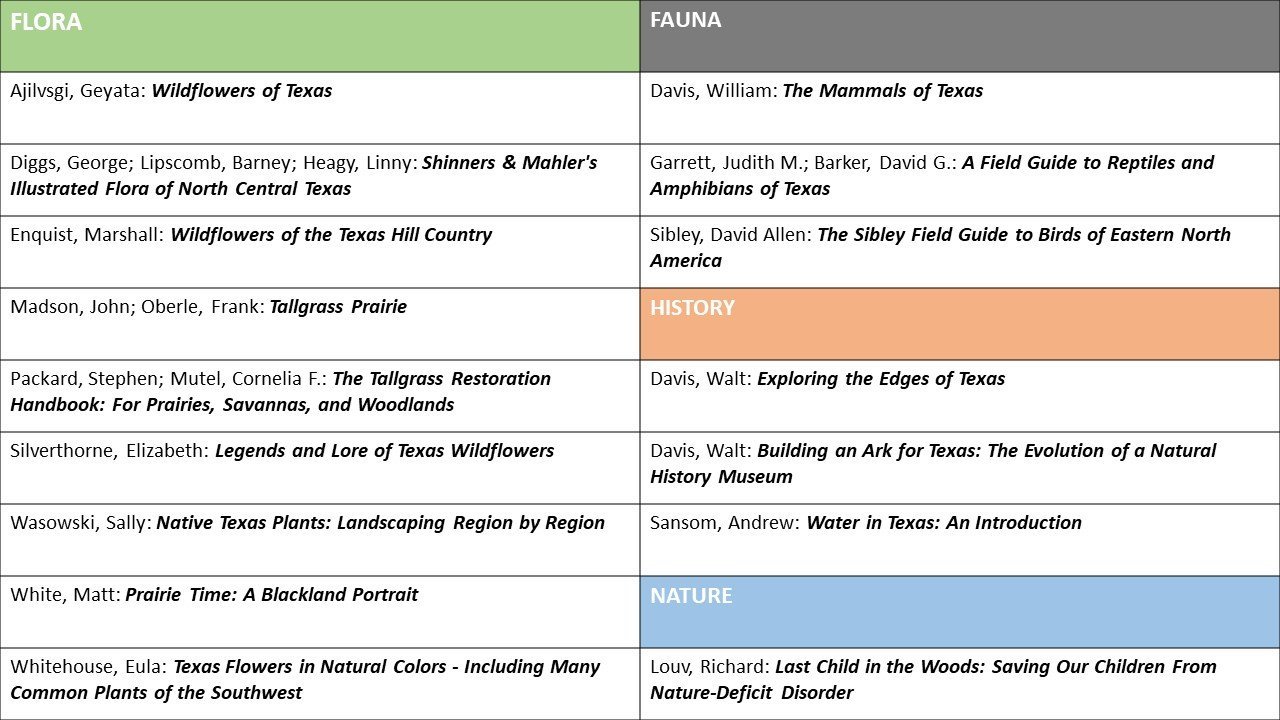

TMN Annual Meeting presenter Becky Rader—whose talk was entitled Project Longevity: Here Today, Gone Tomorrow?—reached out to HCMN Beth Ramey to follow up on a request from one of our attendees for her list of resources. She failed to note the attendee’s name, but since the list is certainly useful for any of us, we offer it here. Ms. Rader’s presentation was delivered on Friday October 22 at 1:45. You may find additional details about her presentation here.

The Hays County chapter of Texas Master Naturalist™ is deeply grateful to TMN State Program Coordinator Michelle Haggarty, Assistant Program Coordinator Mary Pearl Meuth, and all the speakers and volunteers for making the 2021 Annual Meeting another beautifully wrapped and precious gift to Texas Master Naturalists.

Photo courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

…could bring $50 Million per year to Texas

Nature lovers have enjoyed the benefits of significant federal funding landmarks over the decades. Among those funding achievements are the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (1937), Dingell Johnson Act (1950), and the Endangered Species Act (1973). There is a new initiative of similar landmark proportions. This is a 21st century wildlife conservation funding proposal.

A nationwide alliance of government, business, and conservation leaders united to combat one of America’s greatest natural threats—the decline of our fish and wildlife and their natural habitats. Scientists estimate one-third of wildlife species are at risk of becoming threatened or endangered without additional funding.

Where past funding mechanisms have often focused upon hunted animals, this effort would focus upon preventing more than 12,000 species of fish and wildlife from becoming endangered. Over 1,300 of those species are here in Texas. These are called Species of Greatest Conservation Need. To see a list of them, see https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/wild/wildlife_diversity/nongame/tcap/sgcn.phtml

Recently, the bipartisan Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, H.R. 2773 and S. 2372, was filed for the third time. The proposed legislation redirects $1.3 billion in existing royalties from energy and mineral development on federal lands and waters. If passed, Texas could receive about $50 million annually to implement its Texas Conservation Action Plan, without any increase in citizens’ taxes.

For our state, this could mean true transformative change to people and wildlife. It is truly a once-in-a-generation look at how to protect species.

It currently costs hundreds of millions of dollars yearly to address our nation’s threatened and endangered species. With this funding, it is hoped that more proactive measures could be put into place to protect these resources.

The purpose of this bill is to increase and stabilize funding for states to address these concerns. For more information about the federal bill under consideration, see www.TxWildlifeAlliance.org or www.OurNatureUSA.com. What an exciting time to be alive and see what could improve for a nation’s wildlife!

Visiting African wildlife conservation and prosecution officials

Michael Mitchell is a retired Game Warden and an El Camino Real TMN chapter founder, now living in Austin. Conservation of our natural resources has been his focus both professionally and personally. Mike had the privilege throughout his career to hold different positions within the Law Enforcement division. He began his career in 2004 as a field game warden in Cameron, then moved to the Texas Gulf Coast. He completed the final leg as an Assistant Commander at Austin Headquarters. Mike was also a frequent instructor at the Game Warden Training Center, the National Association of Conservation Law Enforcement Chiefs national academy, and the International Conservation Chiefs Academy. In the latter, he focused on coaching conservation and prosecution officials from Ghana, Nigeria, and numerous other African and Latin American countries. He simultaneously led the way in new technologies for Texas game wardens, from social media to mobile apps. One of those won the best app in Texas government. Also a Master Gardener and Master Naturalist, Mike co-authored the first-ever TMN curriculum chapter on Laws and Ethics. He is a frequent speaker at TMN chapters around the state. His current speaking topics include Laws & Ethics, Owl & Cameras, Operation Game Thief, and International Wildlife Trafficking.

Thank You Contributors

Art Arizpe, Mimi Cavender, Michael Mitchell, Constance Quigley, Steve Wilder

Herb is a legend both inside and outside of the HaysMN. To learn more about Herb Smith, click on these Hays Humm articles: Useful Beauty and Online Media Powerhouse. Herb’s obituary in the Austin American-Statesman can be viewed at this link.

Road Trip Discovery Along I-10 in Southern New Mexico

Adjacent to a Rest Stop heading East near Deming - Oct. 2021 - Tom Jones

Naturescapes 2021 Awards

Art Arizpe

The unique beauty of the natural areas within San Marcos inspired the first Naturescapes Photography Contest.

Goals of the contest and exhibit include increasing public awareness of the importance of protecting our natural world and giving photographers at all levels of experience a chance to capture, share, and receive recognition for beautiful and inspiring images. Suggested subjects include natural scenery, wildlife, plants, and people and pets in the natural environment. Our chapter became a co-sponsor of the contest, along with the Hill Country Photography Club, in 2011.

Now in its 17th year, the contest received 235 entries from 34 adult and 2 youth photographers making 2021 one of the biggest years ever. 60 entries were picked for the exhibition and 11 won awards.

Hays County Master Naturalists Mike Davis and Winifred Simon received awards for their stunning work.

Click on any photo and scroll to see full size images:

Other Naturescapes winners are shown below—click and scroll to view full size images of their beautiful photographs:

Boo! Hole Halloween was baaack and better than ever on the evening of October 30 from 4pm to 10pm at Wimberley’s Blue Hole Regional Park. The popular event, sponsored by City of Wimberley Parks and Recreation Department, was free. Families enjoyed costume contests and a Trick-or-Treat trail with candy and games. There were s’mores at the fire pit and a haunted hayride. Southern Wildlife Rehabilitation Center brought their live animal exhibit with spiders, snakes, and opossums.

Wild about Nature, a family education outreach of Hays County Master Naturalist, manned three exhibit tables of bats, creepy crawlies, pelts, skulls and bones—the really cool stuff that especially this time of year gets a bad rap. Visitors rounded out their fall evening with a showing of the movie Hocus Pocus. It was just the right light mix of Halloween fright and fun. And a ghoulish good time was had by all.

A deep and abiding love for this book made me think I could do a review worthy of the HUMM. Each of the umpteen times I have read and referred to it have brought something new; a flash of insight, a hint of meaning, help to understand more deeply some of my own experiences. But the truth is, to do justice to the work, I would have to quote all 277 pages. The meaning that I find in the more poetic, transcendental passages is personal and would do a disservice to readers who will bring their own experience, perspective, and interpretation to the beautiful language, imagery, and observations. I can only recommend that anyone who loves nature read this book and see the world of Tinker Creek brought to life through the eyes of an extraordinary writer. ~ Steve Wilder

At the book’s beginning, the author describes an image of “something powerful playing over us,” “We wake, if we ever wake at all, to mystery, rumors of death, beauty, violence….’Seems like we’re just set down here,’ a woman said to me recently, ‘and don’t nobody know why.’” She observes “An infant who has learned to raise his head has a frank and forthright way of gazing about in bewilderment. He hasn’t the faintest clue where he is, and he aims to learn. Some unwonted, taught pride diverts us from our original intent, which is to explore the neighborhood, view the landscape, to discover at least where it is that we have been so startlingly set down, if we can’t learn why.” Dillard embraces the “where” through meticulous physical observations and the unknowable why through metaphysical questioning in this soaring narrative. “We don’t know what is going on here. If these tremendous events are random combinations of matter run amok, the yield of millions of monkeys at millions of typewriters, then what is it in us, hammered out of those same typewriters, that they ignite?”

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek is a 1974 book by author Annie Dillard and the winner of the 1975 Pulitzer for nonfiction. Chronicling a year and told from a first-person point of view, she details explorations near her Virginia cabin and Tinker Creek, leading to contemplations on nature and life. The book records her careful observations on the flora and fauna she encounters; thoughts on solitude, writing, and religion and touching upon themes of faith, nature, and awareness. Her observations and musings are expressed with a scientist’s discipline, an artist’s eye, the syntax and vocabulary of an English professor, the visionary language and imagery of a poet, and the spiritual reference of a dedicated student of all the world’s religions and pursuits of meaning. Though she does not consider herself a “Nature Writer,” and eschews comparisons of the book to Thoreau’s Walden, her study of the flora and fauna of Tinker Creek in search of deeper meaning is full of careful observations used to mark the path toward understanding. Although it roughly follows a calendar year in its structure, and two of the chapters are titled Winter and Spring, it is more a tapestry of observational perspectives, with chapters entitled Seeing, The Fixed, The Present, Intricacy, Fecundity, and Stalking, as well as chapters titled with religious references.

Beginning the chapter Seeing, Dillard describes a curious habit she had as a child. She would take a precious penny of her own and hide it for someone else to find, then draw chalk marks on the sidewalk pointing toward the penny, saying “Surprise ahead” or “Free money this way.” She would not linger but go home and imagine the excitement of the lucky person enriched by finding her precious penny. The allegory is that the world is in fact planted with pennies of natural phenomena, and if you seek to see them, the purse of your life will be filled with riches. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek takes us through her year of collecting pennies, nuggets of observations of nature along Tinker Creek, and the richness of understanding and the potential meanings they reveal.

The book is full of these pennies of fascinating observations, springing from her solitary explorations of her surroundings during the day and her voracious reading of reference material during the nights. One of my favorite observations, in the Intricacy chapter, concerns her goldfish Ellery in his bowl with a simple elodea plant.

She was in a laboratory, using a powerful microscope, observing the chloroplasts. If you analyze a molecule of chlorophyll itself, what you get is one hundred thirty-six atoms of hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen arranged in an exact and complex ring around a single atom of magnesium. Once, in a laboratory with a dissecting microscope, Dillard observed hemoglobin in the tail of an etherized goldfish. The red blood cells streamed and coursed through the narrow channels in the goldfish’s tail. “They never wavered or slowed or ceased, like the (Tinker) creek itself.” Later, Dillard had the chance to observe chlorophyll-bearing chloroplast cells in the translucent leaves of the elodea plant, which are only two cells thick. “Now: If you remove the atom of magnesium and in its exact place you put an atom of iron, you get a molecule of hemoglobin. The iron atom combines with all the other atoms to make red blood, the streaming dots in the goldfish’s tail. It is, then, a small world there in the goldfish bowl, and a very large one.”

In Seeing, she describes the reaction of patients across America and Europe who had been blinded by cataracts from birth but received surgery from doctors who had discovered a safe procedure. Their reactions varied, but mostly involved seeing various kinds of brightness, a confusion of color patches in which everything seemed dull and in motion. They had no concept of space and depth, confusing it with “roundness.” Seeing, then, is a learned function, and to see truly, we must gather all the information of what is in our field of vision to begin to understand it and its relation to everything in our experience. But all our visual impressions are filtered through a network of ganglia, cutting and splicing what we see, editing it for our brain. She references Donald Carr, who points out that the sense impressions of one-celled animals are not edited for the brain: “This is philosophically interesting in a rather mournful way, since it means that only the simplest animals perceive the universe as it is.”

In The Present, she describes a moment at a gas station after a long day of driving the Interstate. The young gas station attendant has a puppy which Dillard befriends, and in her quiet respite, observing the sunlight and clouds flickering light across the nearby hills, patting the puppy’s taut belly, she loses herself in a meditative reverie, wholly absorbed in the moment and the pure input of stimuli. And she thinks, ”This is it. This is the moment, the present, right now.” But in verbalizing the awareness in her brain, the moment is lost. She observes, “it is ironic that the one thing all religions recognize as separating us from our creator – our very self-consciousness – is also the one thing that divides us from our fellow creatures. It was a bitter birthday present from evolution, cutting us off at both ends.”

Using the creek as an allegory for time, she stands looking upstream. The creek never stops, it is the future, tumbling toward us, the light on the water careening toward us inevitably, freely, and the splash we feel is the present. “I feel as though I stand at the foot of an infinitely high staircase, down which some exuberant spirit is flinging tennis ball after tennis ball, eternally, and the one thing I want in the world is a tennis ball.” Then quoting a subatomic physicist, she wraps the chapter with “everything that has already happened is particles, everything in the future is waves.”

In Fecundity, Dillard looks at the driving force behind evolution, a terrible pressure of birth and growth, and the extravagance of nature in the propagation of species. A shoreline of rock barnacles may leak into the water a million million larvae in a milky cloud. Edwin Way Teale reports that a lone aphid, without a partner, breeding unmolested for a year, would produce so many offspring that, although they are only a tenth of an inch long, together they would extend light years into space. Even the average goldfish lays five thousand eggs. This pressure of growth is a terrible hunger. These billions must eat to reach sexual maturity and pump out more billions of eggs. And what do they eat? Other eggs and creatures and even one another. Evolution loves Death more than it loves you or me. The faster death goes, the faster evolution goes. We value the individual, but Nature values him not a whit. She values supremely the perpetuation of the species and some future mutation that will perhaps result in a more perfect expression of the life force.

In Stalking, Dillard seeks to observe the wary muskrats of the creek. She describes the almost comical gyrations she adopts to try to approach them and uses the example of her stalking as an allegory for our pursuit of an awakening, our achieving an awareness of our surroundings that will give meaning and purpose to our existence. Such instances occur rarely, unexpectedly, and many of us have experienced what seem to be flashes of transcendence, moments of an almost surreal clarity we can’t fully understand or explain. These are the moments Dillard stalks through her honest examination of the natural world. Moments where a divine light seems to shine through a cleft in our three-dimensional world, charging our vision with an eternal light and energy, giving us a glimpse of heightened consciousness. Her description of “seeing the tree with the lights in it” is an eloquent capture of that kind of moment that must be read to be appreciated.

There are so many astounding observations and images throughout the book. A mockingbird with folded wings steps off the roof of a four-story building and just before it would smash into the ground, carefully unfurls its wings and floats onto the grass. Sharks captured in the translucent light of a wave at a beach, roiling and heaving in a feeding frenzy, frozen in a moment like a scorpion in amber. “The sight held awesome wonders: beauty and grace, tangled in a rapture with violence.” Stark yet graceful images of the lives of Eskimos in the unforgiving Arctic. Dillard has an incredible gift for descriptive prose, which lends added poignancy to all her observations. Sometimes her leaning to poetic language (her first book, Tickets for a Prayer Wheel, was a book of poetry) takes the reader into the realm of mystery, offering multiple possible meanings and hints of things unknowable. At times we may wish her to be more definitive, yet the enlightenment she seeks through Nature is the “why” beyond the physical “where” of our world.

Though her detailed investigation of nature is anchored in the science of a Newtonian universe, she introduces Werner Heisenberg’s Principle of Indeterminacy, which states that it is impossible to know both a particle’s velocity and position. It is not that we lack sufficient information to know both, rather we know now for sure there is no knowing. They seem to be as free as dragonflies. If the electron is a muskrat, it cannot be perfectly stalked. Nature’s last veil cannot be removed. This has turned science inside out, with noted physicist Sir Arthur Eddington saying we are left with a universe composed of “mind stuff,” a physical world entirely abstract and without actuality apart from its linkage to consciousness. Another wonders if this world is not so much a great machine as it is a great idea. Such questions among leading scientists are parallels to Dillard’s narrative throughout the book, that the philosophical search for the “why” of our world and the scientific study of our “where” are two faces of a coin, a penny, in a world filled with sparkling pennies.

It seems, as Kierkegaard posited, that “Life is not a puzzle to be solved, but a reality to be experienced.” To which Dillard would add “and appreciated and praised.”