The Hays Humm - June 2020

Tom Jones - Betsy Cross - Constance Quigley

Sculpture by Cypress

Photo by Herb Smith

Article by Mimi Cavender

In what are now so often described as “extraordinary times,” we naturalists can enjoy new opportunities for greater mindfulness. We’ve always approached our beloved natural world with a fascination for the science of it. And some of us have discovered that fine art can be made from it too. It’s this dichotomy - science and art, faithful documentation and gallery photograph - that hovers over our recent conversation with photographer Herb Smith. His quietude is good for these mindful times. He’s painterly, portrait of the artist at home. But wait, he’s enjoyed lifetime achievement in science? We call them Renaissance men, these artist scientists, experts in many things. Want to meet him, the man behind those breathtaking photos? OK, but first let’s look at how each of us as Master Naturalists approach the same dichotomy: science and art - two equally useful ways to be mindful of nature. Which is yours?

Herb Smith

2003 Class - The Wild Things, Photo by Jim McJunkin

In these strangely paused times of Coronavirus-induced social distancing, with fewer volunteer opportunities, we may find more time to sit longer, quietly, in the early morning sparkle, hear the eerie clucking of a yellow-billed cuckoo, sleek and invisible, somewhere high, nearby. We may spend more time now watching the circus at our bird feeders, all flutter and dive, little brown jobs, assorted wrens, titmice, chickadees; the flash of a lesser goldfinch, a house finch, blazing cardinals pausing for seed after hunting moths to stuff into drab little fledglings. And there are bluebirds in our boxes, monarchs on our milkweed, a doe under the deck about to drop her twins, frogs after the rain, and fireflies at dusk. The stars. Then, around ten, out in the mysterious wild dark, Chuck-Will’s-Widows call and respond.

We see and hear and love it all. As Master Naturalists, citizen scientists, we can observe, count, document, and report. We know how to do this mindfulness thing, being still and watchful, letting nature come to us.

Then there are those who go out and look for it. Drives, walks, and volunteer work take us, eyes and ears wide open, out into blowing prairie grasses, Indian-blanketed meadows, fog-drifted dawn cypresses at a low water crossing, and oh so much, heartbreakingly much more. It can be found and captured. Ephemeral no longer, the moment is preserved. We seem driven by this ache of the ephemeral. It’s the oh my god do you see that oh no it’s gone it was so beautiful, that drives the photographers among us to steal and store the wonder, catalog and re-present it, the ephemeral now immortal. These folks drive to the grocery store “with a camera in their lap.”

Photographer Herb Smith Zooms with us from his Wimberley home. Behind him a tall window frames twisting live oaks and bald cypress. We’re reminded of a drawing, a self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, the textures of his face and hair. Long before photography, the Renaissance scientist drew what he saw, captured detail, the ropey veins in his hands, the precise workings of the natural world. His art was both beautiful and useful. Leonardo is said to have chided his student, Raphael, who may have been riffing a little, “First look. Then just draw what you see.”

“I fell in love with photography as a kid.”

As a child in Michigan, Herb loved nature, went to camp in Wisconsin and soon earned the nickname “Natureboy.” He had his own darkroom at twelve and a single lens reflex Exacta V at sixteen. After a pre-med B.A., his yearning to combine science and art took him to Scotland’s Glasgow School of Art, followed by extensive travel in Europe with long hours studying the Masters. He learned, he tells us soberly, “accurate drawing skills were my major goal.” He then received his M.A. from the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Heart Transplant

Pen and Ink Illustration by Herb Smith

Herb’s entire career would be in medical illustration and biomedical communication, first at National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. Then, he was recruited to Houston in 1964 by famed cardiovascular surgeon Michael E. DeBakey.

“He insisted that I come to interview for the job. I was a Michigan boy, and I wasn’t interested in moving to Texas, but he was so persuasive that I met him the next morning at 7:00 in Houston. I spent the day in the operating room. I was so impressed with what they were doing that I took the job on the spot. I called my wife. ‘We’re moving to Texas.’ It ended up being the best position for me in the country.”

Herb worked the next 37 years at Baylor College of Medicine as Director of the departments of Medical Illustration and Audiovisual Education and of Web Development. Herb was the first person to receive the two highest lifetime achievement honors in his field, from the Association of Medical Illustrators and the Biological Photographic Association.

When asked to tell of an extraordinary opportunity as a nature photographer, Herb blew right past his long list of gallery shows and awards nation wide and throughout the Texas Hill Country. Instead, he recalled his work at Baylor College of Medicine. “Those were wild times. DeBakey and the other surgeons were doing really exciting things. I was fortunate to be involved in that.” Herb worked an 80-hour week doing medical illustration. His eye for “telling the story” and accurate detail in the drawings served his need for art and the needs of heart surgeons. Before digital photography or even high-grade videography, documentation of heart surgery was mostly with color slides and 16mm cinematography. He recalls a moment:

“In 1968 I was in the operating room when Dr. Denton Cooley did the first successful heart transplant in the United States. He had the diseased heart in his hands, and he said, ‘Fred, get a photograph of this.’ Fred, the hospital photographer, said ‘I’m out of film.’ An exasperated Cooley asked, ‘Anyone have a camera?’ I had mine as backup for general operating room scenes and ended up taking the only surgical photo of my career, Heart in Hands. It became a double-page spread in Life magazine.”

Heart in Hands

By Herb Smith in Life magazine August 1968

“My wife Susan and I discovered the Texas Hill County and have never looked back.”

In retirement, Herb’s love of nature and photography was free to thrive. “My wife Susan and I discovered the Texas Hill Country and have never looked back.” Herb designed a darkroom in their home near Wimberley just before the arrival of digital photography. “Now it’s a storeroom.” Herb and Susan were in the Hays County Master Naturalists class of 2003, “The Wild Things.” Herb started our Chapter’s first website. “Those were the early days. Things were real simple. I enjoyed doing it a lot.”

Herb is the juror for this year’s Naturescapes Photography Contest, sponsored by the Hill Country Photography Club and the Hays County Master Naturalists. Entry deadline is June 29. Read on for Herb’s responses to questions we asked about his photography.

Autumn Fog

By Herb Smith

How did the Naturescapes Photography Contest come about?

“Todd Derkacz was president of the San Marcos Greenbelt Alliance in 2005 when they decided to sponsor a photography contest. At the time, I was president of the Hill Country Photography Club, and Todd asked me to help organize the contest. It started just in San Marcos but later expanded to all of Hays County. It's still going on.” naturescapes.hcphotoclub.org

His approach to composition?

“There is no good composition in a photograph without a good subject. The technical side of photography is something I think should be a given. But knowing the technical aspects will not necessarily give you a good photograph.”

What is he looking for in composition?

“I’m not conscious of what makes a good photograph. I spot a scene I want to photograph, then look at it through the viewfinder, where I compose the image. I know what I want by the time I trip the shutter to make the image. It may be influenced by my art school training, but it’s not really conscious.”

What are his favorite subjects?

“My work has always been nature related. The photography I do now is landscape work, generally black and white. I did go through a period as a dragonfly photographer.”

An ordinary versus extraordinary photograph?

“I give all the credit there to Mother Nature. Composition comes next, but the subject has to be there.”

What gear does he use?

“A couple of Nikons: a D80 SLR that I had converted for infrared photography, and a D7000 that I use with a zoom lens and tripod most of the time. I also like to experiment with pinhole photography and with a Lensbaby. It’s like an old-fashioned bellows camera in miniature, that gives me control over areas of sharp and soft focus.”

“I most enjoy digital over traditional photography because I can see the image immediately, adjust, and re-take it. It also is much more environmentally friendly than the chemicals of traditional photography, which is very important to me.”

Sachtleben Oaks

By Herb Smith

Software?

“Mostly Photoshop and Lightroom.”

Cell phone?

“It makes it possible to always have a camera at your fingertips, as well as a phone.”

Sharing his photos?

“On my website at herbsmithphotos.com. I also enter photography contests, and I display regularly at the Wimberley Valley Art League Gallery in the Wimberley Community Center.”

How might our Master Naturalist training improve our photography?

“It helps us appreciate what we’re seeing in the natural world.”

How can photography serve our master naturalists’ love of the natural world?

“I think the whole reason for the Master Naturalist program is education, and photos are an important aspect of that. Most of my photos are both documentation and art form.”

So, for the many of us who, always mindful, leave our porch to search out and capture the ephemeral, we have Herb Smith’s example, Leonardo-like, when science and art together produce useful beauty.

Visit herbsmithphotos.com. Then, inspired, pick up a camera - or hey, your phone - and produce some useful beauty.

Herb Smith Gallery

photo by Amy Morrissey

If you grew up in Texas, you probably remember playing with “horny toads”. They were once quite common throughout the Southwest and very popular as pets. In 1993, the Texas Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum) was officially declared the state reptile of Texas. Unfortunately, its range and population have dwindled over the years due to a variety of anthropogenic threats including habitat degradation and destruction, pesticide use, invasive species, and the pet trade. Large-scale agriculture and increasing urbanization have reduced the amount of suitable lizard habitat and increased habitat fragmentation in many areas where they once thrived. Non-native grasses such as Old World Bluestem (Bothriocola spp.) create landscapes that are uninhabitable for horned lizards, and the Red Imported Fire Ant (Solenopsis invicta) directly impacts lizard populations by attacking nests and hatchlings as well as indirectly by preying on or displacing terrestrial invertebrates including the Red Harvester Ant (Pogonomyrmex barbatus), which is the main food source for horned lizards. Today the Texas Horned Lizard is listed as a threatened species by the State of Texas.

Thanks to the dedication of numerous organizations and individuals, the Texas Horned Lizard has been the subject of many years of research, resulting in successful captive breeding programs at several zoos and reintroduction efforts throughout the state. Texas Parks & Wildlife Department (TPWD), Texas Christian University (TCU), the Dallas Zoo, the Fort Worth Zoo (since 2000), and the San Antonio Zoo have coordinated their efforts with private landowners to identify ideal habitats for these tiny lizards. They prefer an arid, sparse landscape that provides them with camouflage, and sandy soil that is ideal for red harvester ants to build their mounds. As 95% of Texas is privately owned, ranches are a logical place for horned lizards to be reintroduced. One of the earliest research programs was through the Dallas Zoo at the Quail Research Ranch in Fisher County. Quail require similar habitat to the horned lizard, so restoring prairies and grasslands to their native state is beneficial to both species and improves native biodiversity overall. In addition to habitat preparation, researchers have developed methods to locate and tag harvester ant mounds, safely eradicate fire ants, and detect released lizards in order to monitor the condition of individual lizards and to assess the status of introduced populations over time.

One such project is San Antonio Zoo’s Texas Horned Lizard Reintroduction Project which is led by Andy Gluesenkamp, Director of Conservation in the zoo’s Center for Conservation and Research. The goals of this project are to restore healthy lizard populations to areas where they have disappeared and to develop methods for captive reproduction, site assessment and management, and population monitoring to be shared with the conservation community. The reintroduction effort involves several steps: site assessment, habitat management, release of captive-born lizards, and post-release monitoring. Selection of candidate release sites is based on several criteria, including a minimum of 200 acres of good- to high-quality habitat. Site assessment uses boots-on-the-ground surveys and TPWD’s GIS model of plant communities ranked according to quality of lizard habitat.

Andy is currently preparing a release site on a private ranch near Cypress Mill in Blanco County. He has identified several other candidate sites in Bexar, Blanco, Hays, Kerr, and Travis counties (including one near Westcave Preserve). Pre-release habitat management includes removal of invasive species, brush-thinning via mechanical clearing or prescribed fire, and promotion of native grasses and forbs to restore a mosaic of open areas and shelter sites. Volunteers at these sites are tasked with locating and marking harvester ant mounds with a plate (GPS marker). They then pin flags into fire ant nests within a 50-meter radius of the harvester ant mound (pink flags in photo). The final step is to inject soapy hot water into the fire ant nests with a portable hot water pressure washer (the “fire ant buster”). The site preparation team cannot use Amdro or similar baits because it will kill the harvester ants along with the targeted fire ants. Treatments are carefully recorded using a spreadsheet containing GPS coordinates of each harvester ant mound, an indication of whether it has been surveyed for fire ant mounds, and whether the fire ant nests have been treated. They have also created a color-coded Google map of the area with the same information. In order to establish viable horned lizard populations, this project plans to release 100 young lizards per site for three consecutive years, followed by 25 lizards every other year until a reproducing population is established. Individual lizards are genotyped prior to release which will allow them to identify individual released lizards (and their offspring) using cloacal swabs or scat samples collected onsite.

This slideshow includes photos of the work in progress. In the Google Map photo, the red dots have been treated; the yellow dots have pin flags ready for treatment; the blue dots still need to be scouted for fire ants.

Of course the release of the horned lizards will be a very exciting part of this project. The most interesting and educational aspect, however, will likely be ongoing tracking and monitoring of the horned lizard population in the reintroduced areas. Lizards can be tracked using GPS chips placed under their skin or transmitters mounted on their backs (see photo below). They are not difficult to locate after release, as they do not venture far from their food source. In this particular project, post-release monitoring will employ visual surveys and a specially trained horned lizard detection canine (Chiron-K9) that can detect live or dead lizards, shed skin, scat, and eggs. This approach promises to reduce stress on lizards compared to traditional identification and tracking methods (toe-clipping, marking with paint, and telemetry backpacks) and greatly increase detection rates.

Over the years, many Texas Horned Lizards (THLs) have been relocated and released into new habitats, with mixed results. An East Texas study found that the coachwhip snake is a common predator (along with raccoons and skunks) and would consume the horned lizards along with their tracking devices. This was likely due to excessive brush in the habitat, which allowed the predators to easily conceal themselves. Based on the results of release efforts at MUSE and Mason Mountain WMAs, THL survival rates in the first year have been low, but the lizards have successfully reproduced and their population can be sustained if the habitat is maintained and their food source is not compromised. The Quail Research Ranch has had great luck with their research projects for many years, and much has been learned about the THL’s diet, natural gender ratios, habitat preference, and activity patterns. The San Antonio Zoo’s reintroduction project has a wealth of knowledge and scientific studies to support their efforts in Central Texas.

The Texas Horned Lizard is the 2019 HCMN class mascot/spirit animal. And now we have an official, approved project to support the San Antonio Zoo in reintroducing Texas Horned Lizards to their native habitat in and around Hays County! Project 2001 is the first official Hays County Master Naturalist project of 2020. If you are interested in volunteering, please check the calendar. We will be adding new opportunities as they arise. If you have any questions or would like to be added to the volunteer list for updates on this project, please contact Jan Wolfe at janowolfe@gmail.com.

The formal description of Project 2001 from VMS: “Managing, maintaining, and improving habitat in Hays County and adjacent counties for the State Reptile of Texas, the Texas Horned Lizard, by identifying and eliminating ant species that are dangerous to the horned lizard (fire ants) and locating/marking ant species that are a primary food source for the horned lizards (harvester ants). This work will be done in preparation for the reintroduction of large numbers of captive-reared horned lizards to areas of their native range where they have been extirpated.”

Some neat facts about the Texas Horned Lizard (THL):

THL coloration can vary at different temperatures, but the real variation with color happens because over time natural selection selects for horned lizards that match their environment. You can see from the photos in this article that they vary from rusty brown to gray in their camouflage, and that their markings can be quite diverse.

Because THLs can occur in more vegetated habitats than some other horned lizard species, the white line down their back actually helps them blend into grassland areas--it can look like another dried grass stem!

THLs can spurt blood from their eyes (up to 5 feet away!) as a defense against predators, and their blood tastes awful, so any predator that gets a mouthful of that usually decides to leave.

THL blood is extremely distasteful to canines but the blood defense doesn’t work on birds, another predator of the THL.

THLs can puff themselves up to scare away predators too.

THLs can collect and drink rainwater from their backs.

The scientific name Phrynosoma cornutum literally means “toad-body horned”.

THLs have a 6-year life span, but they don’t reach sexual maturity until they’re 2 years old.

The THL female lays from 10-30 eggs (even up to 42!) in the sand and buries them about six inches deep. She then leaves them to fend for themselves.

REFERENCES:

Texas Parks and Wildlife link

San Antonio Zoo Texas Horned Lizard Reintroduction Project link

Rivard Report link

Fort Worth Zoo link

Horned Lizard Conservation Society link

Blood shooting adaptation link

Fun facts link

Wiki references-link

Where have all the Quail Gone? link

Chiron-K9 website – lizard-sniffing dogs link

A field guide-link

East Texas reintroduction project-link

Quail Research Ranch (Dallas Zoo) link

Meet Your Master Naturalist

2011 Class Painted Buntings

Susan and her Shetland sheepdog, Kit. I train my dogs to be therapy dogs – participating in animal assisted therapy and hospice visits. We volunteer through Divine Canines.

Susan Kimmel-Lines

About Me: I have over 35 years of experience in communications, marketing, public information and outreach. I have managed Austin Energy’s Marketing department since 2014. Prior to that, I managed marketing functions for various semiconductor firms, including AMD and Freescale/Motorola, as well Symantec/Blue Coat and Lockheed Martin. I have a B.A. in Fine Arts from St. Edwards University and an M.S in Integrated Marketing Communications from the Reed School of Journalism, West Virginia University. I am an avid beekeeper and volunteer at the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center, gardener, supporter of Divine Canines Therapy Dogs and all around lover of nature, dogs, cats, birds and rat snakes.

You May Not Know: In addition to my volunteer time as a Master Naturalist, I keep bees. Currently I have two hives behind my house and two active hives out at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. I’ve worked bees for ~10+ years. Profound fascination and pure curiosity were, and still are the primary motivators for keeping bees – and of course the honey is an added gift!

Bee Boxes

FAV Master Naturalist Activity: The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center has a dear and special place in my heart and is my favorite project/activity. I am out there almost every weekend throughout the year and at special events like Nature Nights. I absolutely adore sharing my knowledge of the plants and animals in hopes of inspiring curiosity and a love of nature in all of the visitors – children and adults, young and old.

Bird I most identify with: You might find this really hard to believe, but the bird I would wish to be, if I were ever a bird, would be the Black Vulture (Coragyps atratus). Think about it, you are probably never lacking in food, you get to hang out with all of your friends – in high places, like transformer towers, high-rises – you get to soar at high altitudes for hours with little effort, you maintain monogamous, long-term pair bonds and develop strong social kin bonds, you can eat just about anything. . .but no one is really interested in eating you. For a bird, I think that all sounds pretty good!

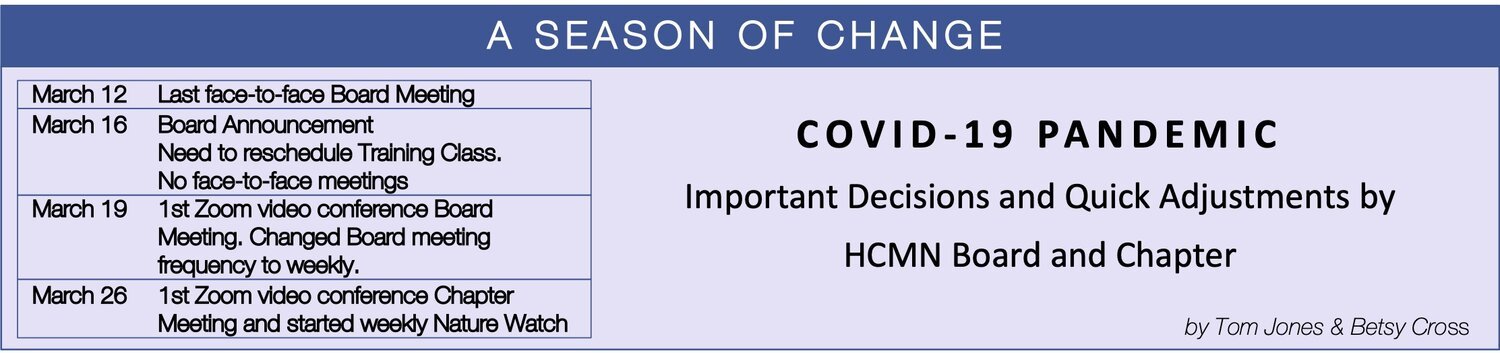

All of us are impacted by the COVID-19 virus pandemic, having made changes to the way we live, work and volunteer. To fulfill our core mission, the HCMN Chapter had to quickly adjust to new guidelines and requirements from our sponsor organizations. A review of how this was accomplished highlights an experienced Board team that quickly reacted and a strong Membership base that utilized the Chapter's robust technology resources to meet this challenge. I reached out to our Leadership team and Members for comment on their actions in this Season of Change.

Susan Neill, President: “In early March, we were concerned about this new virus that was starting to circulate, but were still going to meetings, to classes, and volunteering among our many activities. We went from concern about some people getting sick and possibly having to work through excessive absenteeism in the class to a total shutdown within a matter of weeks. The situation was changing rapidly. The board instituted weekly calls to cover all the new issues rather than wait for our routine monthly meeting. The chapter started weekly calls to allow folks to touch base and share. The class was rescheduled to be completed through online classes continuing through the fall. This has been a time to adapt and be flexible. This pandemic has brought us new perspectives and helped us find ways to connect with each other. I want to thank all of our chapter members for all that you have done during this difficult period to help maintain our connections.”

Dick Barham, Vice President: “My experience using Zoom has been a positive one. Six weeks ago I had never heard of Zoom and being technology-challenged I had my initial reservations. However, in contacting prospective speakers for our monthly meetings, when I explained that they would need to make a presentation via Zoom, no one balked. In fact, our July speaker, who is an author and naturalist, will be "Zooming in" from Wisconsin. I would hope that our weekly and monthly meetings can continue using this format until we can resume in-person meetings.”

Forum Posts & Views: Note the steep increase in activity from March -May 2020.

HaysMN Forum: The HaysMN Forum was established in 2008 to provide Master Naturalists with a private place to share nature observations, photos, ask/answer questions and discuss issues. No one foresaw the need and value of the forum in a pandemic which created restrictions on direct communication. Over the last three months, membership and participation in the Forum has increased. The recent addition of the HaysMNPhoto forum expanded on the original idea, allowing members to share beautiful high-resolution photos and short videos. These forums are now providing a place of calm in this stressful storm, where we can focus on the beauty and wonder of nature. The chart shows how the Forum activity level has risen from January to May of this year. You can visit the HayMN Forum on the web at https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/haysmn .

Mark Wojcik, New Class Director: - “We are extremely fortunate to have a dedicated group of presenters who are willing to continue our 2020 class 100% online using Zoom and hosted by members of the Training Committee. While everyone misses the field trips and site visits that characterize our usual classes, the online approach is the only way we can ensure completing the class without any risk to the participants. Despite the sudden changes, the online classes are very interactive with lots of chat and questions. Part of the 2020 class has opted for the online version, and part of the class has been guaranteed space in the 2021 class in the hope it will return to the traditional format.”

Betsy Cross, Zoom Meetings: Until recently most of us thought of “zoom” in the way my faded-red Merriam Webster describes it - as a verb: to move with a loud low hum or buzz; to go speedily; to focus a camera or microscope on an object using a zoom lens. Today if you Google the word “zoom”, you’re not likely to see these definitions at the top of the list or even three pages in. Instead you see Zoom Video Conferencing, Zoom Cloud Meetings, Zoom YouTube, and How to Combat Zoom Fatigue. In early March, who among us knew about Zoom Cloud Meetings, let alone Zoom Fatigue?

The last 60 days have altered our perspectives just a tad. The rapid adoption of Zoom Meeting technology to serve our chapter in this changing landscape has challenged our imaginations, our skill sets, and sometimes our patience. But with its help, we have uncovered an array of new ideas and opportunities to continue our ongoing mission and keep folks connected. As I consider the speedy response of the HCMN leadership, the membership at large, and individual contributors who have stepped up in the face of their technology discomfort, these words come to mind – dedication, resilience, sustainability, creativity, conviction, courage, and community.

So, continue to go speedily, keep hummin’ and buzzin’, take out your zoom lens. We invite all of you to join us for our next Zoom Meeting. And don’t be afraid to bring your photos and your stories to our weekly online Nature Watch and Social Hour. We will help you share your screens.

Chris Middleton, E-Nature: I was thinking about how Master Naturalists could accrue hours in a COVID-19/stay-at-home world when I threw out an idea. That was my job at the end of my career - throw out lots of ideas and see what sticks. That one stuck with me. Schools in Hays County were closed. Parents/teachers needed ways to distract kids from disruption of their normal routines. Creating a new digital presence focused on kids seemed like a natural extension of our mission. And thus E-Nature was born. A team of Master Naturalists, many current or former teachers, quickly formed and we created an E-Nature for Kids Facebook page and a new E-Nature for Kids of All Ages web resource page.

As we moved forward, it became apparent that, in these difficult times, our Master Naturalist community was also turning to the natural world. We have lots of keen observers among us who were documenting their observations on the MN Google Group. Many gave us permission to use their pictures/videos/stories. Our Facebook page now has over 300 followers and we continue to grow our digital presence. Our hope for the future is this - even as our world starts opening up, we will continue to grow this new digital presence as a new avenue for spreading our appreciation for the natural world around us. If you have photos/videos, stories, or other observations you think worthy of sharing, please let us know by sending them to enature@haysmn.org.

THANK YOU NEWSLETTER CONTRIBUTORS

Roger K. Allen, Dick Barham, Mimi Cavender, Andy Gluesenkamp, Dell and Gerin Hood, Susan Kimmel-Lines, Chris Middleton, Susan Neill, Herb Smith, Mark Wojcik, Susan Zimmerman

Fawn, photo by Constance Quigley

Title block photos by Mimi Cavender

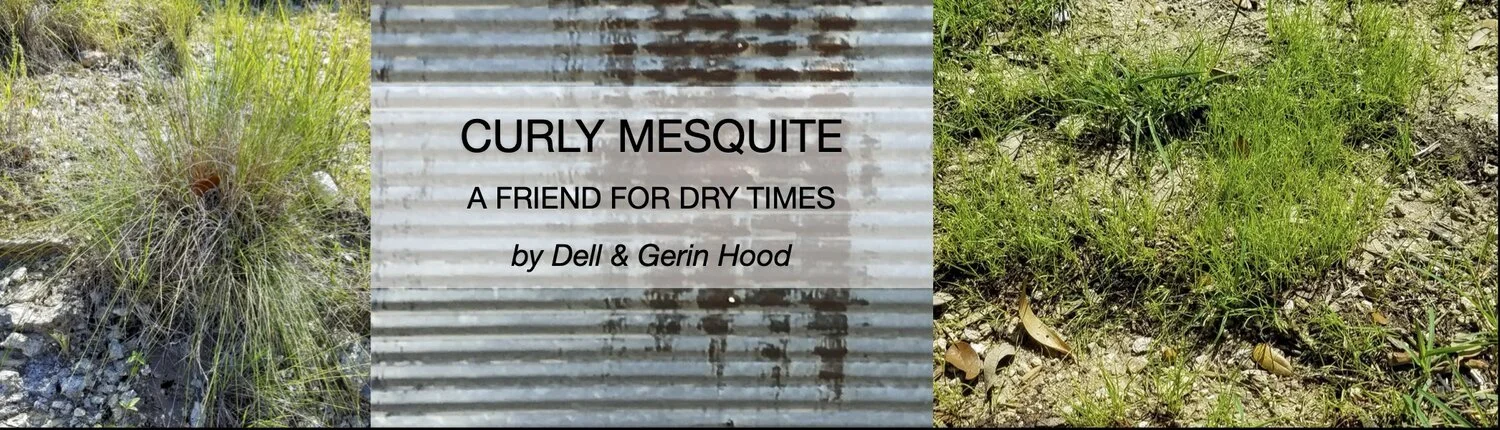

It’s been only two generations since part of central Texas was home to the vast short-grass prairie that extended from south Texas to the Canadian border and beyond, and westward to the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Those of us of a certain age who grew up on the Edwards Plateau may remember the time before extensive urban and suburban sprawl turned ranchland into rural subdivisions. Ranching on this prairie was possible due to the abundance of nutritious and palatable grasses which at one time fed millions of cattle and sheep, as they had buffalo and antelope before that.

We may know some of those grasses – the bluestems, gramas, and buffalo grass. As important as these to the livestock industry but less familiar to most of us is a grass without many relatives and with a curious name which itself has an interesting history – Curly mesquite, or Hilaria berlangeri botanically. A grass of dry areas, able to thrive with as little as 15 inches of rain, in physical form it is a perennial tufted grass with slender erect stems from 4 to 12 inches tall with soft hairs at the nodes; thin (1/8th inch), usually short flat leaf blades mostly crowded around the base of the plant and scabrous (rough to the touch); the plant spreading via stolons or rhizomes as well as seeds. The seed head is a single spike with up to eight clusters of spikelets.

Hays County is at the eastern edge of the range for Curly mesquite, which extends across the Edwards Plateau into southern New Mexico and Arizona and south into neighboring areas of Mexico. It does well on sunny rocky slopes with calcareous soils, in areas not favored by many other grasses. It is an important range grass in semi-desert areas, and because the leaves cure (dry out) on the ground in winter, it can be grazed throughout the year and if given a rest period comes back after heavy grazing. The Manual of the Grasses of the United States, first published in 1935 says, “Curly mesquite is the dominant ‘short grass’ of the Texas plains.”

Its drought-hardiness is one reason curly mesquite is one of the three native grass species included in the Habiturf seed mixture available as a replacement for non-native lawn grasses. The other two in the mix, buffalo grass and blue grama, share this desirable quality, as well as being short grasses that form a short soft turf which does not need frequent mowing. As the climate of central Texas moves into a drier and hotter phase, using more of these resilient native grasses in our managed landscapes seems the rational choice as we adapt our homesteads to new environmental challenges.

The genus Hilaria occurs only in the southwestern U.S., adjoining areas of Mexico and in Guatemala; there are five species in the U.S. (Hitchcock), with three (Correll & Johnson) or two (Shaw) of these native to Texas. What caught my interest in curly mesquite were some curious details behind both the genus and species names, which I could see were based on names of people, and the single occurrence of the name Berlanger in the flora of Texas. The name Hilaria was created in 1813 in honor of the French botanist Augustin Saint-Hilaire (1779-1853) by the trio of Friedrich Humboldt (1769-1859, Prussian naturalist and geographer of Humboldt Current fame), Aimé Bonpland (1773-1858, French explorer and botanist who traveled in South America with Humboldt), and Carl Sigismund Kunth (1788-1850, Prussian botanist who also worked with Humboldt and illustrated many of his descriptions for publication). Together, these four are responsible for cataloging and describing hundreds of species of mainly South American plants and for expanding and organizing the Linnaean classification system by including features of the whole plant in their classifications, where Linnaeus focused on what he considered the few “essential” features of the inflorescence.

The species of curly mesquite, berlangeri, presents a puzzle. This name for this grass is attributed to a Prussian physician who also became a noted bibliographer of botany, Ernst Gottlieb Steudel (1783-1856) who worked on describing, organizing and systematizing the findings of others, including the four men named above. He did little collecting himself but acquired an herbarium of 20,000 plants (many of them grasses) sent to him by his contacts. When he died his collection was acquired first by a French nobleman who later donated all or parts of it to Oxford University. There was a French botanist, Charles Paulus Bélanger (1805-1881) who specialized in ferns and mushrooms and who collected in India before becoming director of a botanical garden at St. Pierre on the Caribbean island of Martinique. There is no evidence indicating Bélanger visited the parts of North America where curly mesquite was native.

The most plausible answer to how Bélanger’s name was given to a Texas grass is suggested by Hitchcock. The French-Mexican naturalist Jean-Louis Berlandier (1803-1851) was employed by the Mexican government as a biologist and plant specialist; he spent most of his adult life traveling and collecting in Mexico and pre-independence Texas. Hitchcock states that he collected the type specimen for Curly mesquite in Mexico and says, “Belanger is evidently an error for Berlandier…” Thus it seems Steudel was to some degree acquainted with the collections of both men and confused the two French names when he wrote the botanical description of Curly mesquite now accepted as the authority. Is it fancy to imagine that after a long tiring day examining sheets of preserved plants from Martinique by Bélanger he picks up one by Berlandier, assumes it was by the former, and then misspells his source’s name?

All of which supports the view that the history of botany and botanists can be just as fascinating and informative as the field of botany itself. We can appreciate the efforts of the hundreds of people who created and organized the information we now have about the plants in our own areas as well as across the expanses of Texas.

As a last note to this admittedly inconsequential information, I learned a new word during the research: agrostologist, defined as a specialist in the systematic botany of the grasses. So all was not for naught.

Sources:

1. Ernest Sohns. “The genus Hilaria (Gramineae).” Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 46 (10), October 1956.

2. Correll & Johnston. Manual of the Vascular Plants of Texas, University of Texas, 1979.

3. A. S. Hitchcock. Manual of the Grasses of the U.S., 2nd ed., Dover Publication, 1971.

4. Grass - Yearbook of Agriculture 1948, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

5. Robert B. Shaw. Guide to Texas Grasses. Texas A&M University Press, 2012.

6. Biodiversity Heritage Library

7. Texas State Historical Association Online Handbook: Berlandier, Jean-Louis.

8. Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center

The plant derives its name from the clasping leaf that occurs alternately on the stems.

The Clasping Coneflower, Dracopis amplexicaulis, stands erect at up to 39 inches (100 cm) with multiple branches beginning halfway up the stem (a branched raceme or panicle). This annual member of the Asteraceae Family (Aster Family) produces many seeds. If not controlled, these plants will become abundant in a garden (Lone Star Wildflowers, Lashara J. Nieland and Willa F. Finley). The genus Dracopis only contains this one species in North America (Wikipedia).

Flowers

The flower looks remarkably like Black-eyed Susan except the peduncle, pedicels, and sepals are glabrous (having no hairs). Flowering occurs from April through July (Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center Plant Database). The ray flower grows up to 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) in diameter. The two toned yellow petals of the ray flowers form a bright yellow outer ring and a darker yellow inner ring that surrounds the 1 inch (2.5 cm) diameter disk flowers. The disk flowers cluster in a Fibonacci pattern and bloom from the base to the crown.

Leaves

Screenshot of Roger’s clasping coneflower presentation via Zoom.

Zoom meeting shared on Nature Watch

The plant derives its name from the clasping leaf that occurs alternately on the stems, but the shape varies depending on its age. Amplexicaulis means “clasping the stem.”(Lone Star Wildflowers, Lashara J. Nieland and Willa F. Finley). The younger leaves appear more heart shaped and are 1.5- 3 inches (3.9-7.8 cm) long and 1-1.5 inches (2.5-3.9 cm) wide, but the older leaves grow up to 7 inches (17.8 cm) long and 3 inches (7.8 cm) in width and have more of a lanceolate shape with a winged stem about 1.5 inches in length. All leaves are entire (margins without teeth or lobes).

Range

This species, native to Texas, can be found in well water ditches and fields in the south central and southeastern United States (USDA Plants Database). The flower can be mistaken for other species from a distance.

By Mimi Cavender

Your Hays County Master Naturalist 2020 Class reporter’s reporting skills leave a lot to be desired. Last month we were so sure we’d solved the Buda Beaver mystery. Briskly crossing signals, we then jumped athletically to several conclusions, one being that there was indeed a mystery to be solved. And aha! the game was afoot. The internet, replete with invasive nutria news, came up all cute white muzzles and orange teeth. Irresistible. Great local wildlife info, right? Yes! And no.

With thanks, again, and all credit to our original source, HCMN classmate Cheryl Moczegemba, we announce an update: Mystery re-solved! Those are indeed beavers in Buda. They’re damming a large rainwater retention pond, delighting nature lovers and frustrating safety-minded city engineers. But the City of Buda has been sensitive to the dilemma, partnering with Texas Wildlife Services to install beaver-friendly flow control structures in the pond. According to TWS director, Michael Bodenchuk, “This innovative approach will protect the wetland, wildlife, and the neighborhood.”

But how, exactly? What’s the new gadget, installed in a day, that gives you your beavers and flood protection too? That is your new mystery!

Clue: It involves a very specific beaver behavior. Discover it in the City's colorful PDF with great photos here.