The Hays Humm - September 2021

The Hays Humm

Award Winning Online Magazine - September 2021

Tom Jones - Betsy Cross - Constance Quigley - Mimi Cavender - Steve Wilder

“The oldest task in human history is to live on a piece of land without spoiling it.” — Aldo Leopold

“We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson

Man is a product of nature. We are totally dependent on Nature; that’s why we call it Mother Nature. Living in harmony with our mother seems like such a simple concept, but history has proven it to be anything but simple. Perceiving ourselves as the pinnacle of creation, we somehow believe ourselves to be rulers of the world, who should “tame” nature to make it serve our human needs and our concepts of beauty and order. Talking tough love, Nature might remind us, “I brought you into this world. I can take you out.” We should be clear eyed enough to recognize that statement as defining our relationship with Nature. Our misunderstanding of and disregard for Nature’s laws and processes has long roots in history and has taken us to the brink of requiring drastic remedies to restore a natural balance before Nature “takes us out.”

Let’s recall our national history, face the results locally, and consider a home remedy.

Our History: Manifest Destiny

In 1845, two years before John Meusebach and Texas German immigrants signed their peaceful coexistence treaty with six Fredericksburg area Comanche chiefs, back in New York popular magazine editor John O'Sullivan had coined the term manifest destiny to encourage acceptance of Texas into the United States. The term came to describe the American imperialist mindset. It was a widely held cultural belief throughout 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America. There were three basic themes to manifest destiny:

The special virtues of the American people and their institutions

The mission of the United States to redeem and remake the American West in the image of the agrarian East

An irresistible destiny to accomplish this essential duty

The belief that it was Americans’ “duty” to tame the West was used to justify the genocide of Native Americans, the Mexican-American War, the expansion of slavery into Texas, and the negotiation of the Oregon Boundary Dispute in the early 1800s. Nothing was allowed to stand in the way of “progress.” A Cherokee elder observed, “The western settler’s mindset is ‘I have rights.’ The mindset of indigenous peoples is ‘We have responsibilities.’” Private property rights, especially, have evolved over the last two centuries and are very much alive and well, for better and for worse. The history of America’s—and Texas’—wilderness is one of conflict between our love of Nature and our urge to own and use it. Link to Boston Review article.

Early European settler families in Hays County lived lightly on land recently accruing from the remaining Comanche groups or Mexican landholders, with only animals and hand tools to clear essential space for farming or grazing. Claiborne Kyle built his juniper log home overlooking the Blanco River in 1850; it eventually became Hays County’s first park.

James Winters’ businesses included hand-made fine furniture and a prosperous mill on nearby Cypress Creek around the time family friend Sam Houston was running for governor of the new state. Early Texans cherished and used the land. For a long while, limited available labor and technology prevented our destroying whole ecosystems, as had already been done in parts of the urban Northeast. We modern Texans honor our land-gentle forebears when we preserve the echoes of wild lands we still have from them.

Grand Canyon National Park, from the North Rim — National Park Service

The rights of enterprise, private or public, also have their history. Protections of our wildlands have been sporadic. In 1908 very few people other than Native Americans had ever seen the Grand Canyon. When Theodore Roosevelt was asked to visit, the state of Arizona had begun preparing to mine the Grand Canyon. Upon viewing the magnificence of the canyon, he ordered, “Leave it as it is.” That simple statement began the process of preserving the Grand Canyon as a National Park to join the likes of Yellowstone (1872) and of Sequoia and Yosemite (1890). The National Park Service was established in 1916. However, the philosophy of “leave it as it is” was reserved for only the most spectacular and precious of our natural landscapes. Since the mid-twentieth century, the states have picked up some of the slack, but percentage of total U.S. land area preserved as park and wildland lags behind many other developed countries. Click for more information.

The Manifest Result

The development of our land and resources has been a voracious, often rapacious energy that has resulted in the reduction of native habitat to the point where only 5% of the lower 48 states is anywhere near its pristine ecological state. In the last 50 years unconstrained development has caused the loss of 3 billion birds in North America, a third of our bird population. The United Nations reported that in the next 20 years we may lose one million species to extinction. Texas may lose its fair share.

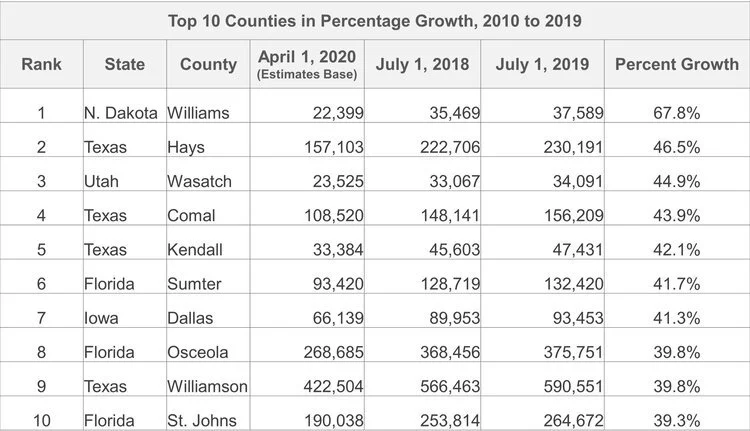

On a global scale, coral reefs are flickering out beneath the oceans, and rainforests are desiccating into savannahs. Nature is being lost at a rate tens to hundreds of times higher than the average over the past 10 thousand years, according to the U.N. global assessment report. The biomass of wild mammals has fallen by 82%, natural ecosystems have lost about half their area, and a million species are at risk of extinction – all largely due to human actions, according to the study, compiled over three years by more than 450 scientists and diplomats. One may assume similar consequences are happening in our own back yard. From 2010 to 2019, Hays County was the second fastest growing county in the U.S., based on percentage of population growth. Our neighbor to the south, Comal County, was fourth. Kendall County was fifth. Three of the top ten fastest growing counties in the U.S. are right here in the Texas Hill Country.

Our conflict around how to love and use the land is best revealed in some recent Hays County suburban development. Large areas of new-build lots, large and small, are scraped—cleared of native vegetation —and then completely replanted with manicured turf grass and nursery trees in an expensive imitation of Texas nature. Bald cypress and sycamore saplings are native species but are no longer in their natural riparian environment; artfully landscaped “dry creeks” stand in for the real thing. The Texas Hill Country is now increasingly yielding to this type of scrape and shape development. We’re losing old growth woods and the wildlife diversity they provide. Those homeowners hear only distant birdsong. Just beyond the back fences, the remaining wild woods of huge old oaks, cedar elm, and juniper are lovely, dark, and deep. And in five years? Fifty?

This tremendous growth in Central Texas comes at the expense of native habitat, and we are seeing a devastating loss of biomass and biodiversity. Protections aren’t keeping up. That’s where we come in.

Possible Solutions: large and small

Blake Hendon is a Wildlife Biologist with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. In his presentation to the Hays County Master Naturalist Training Class of 2020, he explained how development results in habitat fragmentation. Contiguous wild areas are being disconnected, resulting in reduction of total natural area, loss of habitat for wildlife, and introduction of invasive species.

Hendon has designated some useful terms for biogeography altered by development. He calls large contiguous still-wild areas “mainlands;” they retain native characteristics and habitats and preserve native fauna and flora. These mainlands are surrounded by islands of relatively large undeveloped properties (100+ acres), which will host the most species, and smaller properties (20-100 acres), which are more likely to lose the species hosted by the mainland. If a smaller property is adjacent to a mainland, it may become a corridor, providing connections animals can use to easily and safely move between it and other plots of land.

When asked “What can owners of small property (less than 20 acres) do to help offset the effects of fragmentation,” Hendon responded that small patches were important, but usually insufficient in meeting most conservation goals. That was disheartening news for those of us who own small acreage, but the limitations are in keeping with the goals of TPWD and the resources they have to apply to ranchland conservation. Read Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Land and Water Stewardship Plan, 2015, here:

But I began wondering how we as a group of property owners with fewer than 20 acres might manage our small properties to contribute to the conservation of natural habitat and support of native flora and fauna? Small, unconnected properties—our home islands—do not alone offer the space or resources required by a whole ecosystem, but together as a vast network of islands, an archipelago—they do the job. We have only to manage them thoughtfully. Here’s how:

1. We can provide habitat—native cover, food, and water—for many important members of the ecosystem. These include a variety of insects, amphibians, pollinators, migrators, and subsoil life forms that provide fertility and nutrition to our grasses and landscape. Visit the Patsy Glenn Refuge in Wimberley to see the difference some seed feeders, native cover, water, and a few branch piles can make. This tiny 1.8-acre island of Hays wilderness—tucked among a large ranch, Blue Hole Park, a retirement center and a supermarket—is alive with birds! Our home patch can emulate some of this. Revisit Tom Jones’ article Working the Brush Piles at Patsy Glenn Refuge in the June 2021 Hays Humm.

Brush piles slow runoff, prevent erosion, help restore natural vegetation, shape landscape, and provide shelter for wildlife.

Two years ago the entire length of a friend’s eroded, rocky, two-acre front yard inherited a brush pile from the city’s roadside cedar whackers. He’d actually asked the workers to stack it there, and the neighbors were scandalized! Two summers later, a greater diversity of wild plants has intergrown and overgrown the decomposing branches to become a high berm full of wildflowers and wildlife. How many plant species do you see? Another small lot, on a hillside above Wimberley, recycles their brush to control erosion on the slope. Instead of waiting for the burn ban to lift so we can launch pollutants into the atmosphere, why not slow runoff from the precious rain we get and create shelter for birds in the bargain? The brush will naturally decompose. Bet you’ll find more.

2. By learning the nature of our property and its history, we can leave intact or restore native plants, which have historically provided shelter and nutrition for native wildlife on our land. Texas native species to value and preserve on our property—or to introduce there—might include these beauties:Collect and plant seeds of these Texas natives as you find them. Some are available now in nurseries. But to be sure you’re buying true Texas natives, with all their drought tolerance, freeze tolerance, pest resistance, their beauty and value in the ecosystem—read up! Here are some resources:

The Hill Country chapter (in Wimberley) of the Texas Native Plant Society

https://www.facebook.com/groups/HillCountryChapteroftheNativePlantSocietyofTexas/Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center: Native Plant Lists

https://www.wildflower.org/plants-mainTexas A&M Horticulture: Native Ornamentals

https://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/ornamentals/natives.HTM

3. We can remove non-native and invasive species. We might start with our lawns. There are more than 40 million acres devoted to non-native turf grasses across the U.S. If we only cut them back to half and plant native plants and grasses in the other half, we will contribute 20 million acres to native habitat, and that is more acreage than 13 of our largest national parks combined, including Denali and Yellowstone! Scaled down for Hays County, the numbers would still impress.

Traditional suburbia’s St. Augustine (Florida!) lawn grass is a non-native water guzzler and is fungus and pest prone. Texans are finally replacing it with the great turf and bunch grasses available now as sensible, beautiful alternatives to our grandfather’s Sunday mowing chore.

Some other species to remove and replace with natives are the following; no matter how attractive they might seem, they are genuinely invasive—they’re an ecological or commercial hazard: they aggressively crowd out useful native plants, often become monocultures, and have little value for us or for wildlife. Here’s a partial rogue’s gallery:

See an eye-opening pamphlet with photos of local invasive plants. How many are on your property? As a resource for restoration plants, again the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center is more than just wildflowers. To browse native plant and grass choices for your property, also try Texas Hill Country native plant growers Native American Seed for detailed planting advice and spectacular catalogs.

So, in doing simple things in our network of home spaces, our archipelago, collectively we decrease the distance of travel required by species to find suitable habitat. We increase the total population of native flora and fauna. We help stabilize and maintain biomass diversity now being lost to fragmentation. The landscape will begin to look and function again like our memory—or our dream—of Texas!

Each native home island in our Hays archipelago will contribute to keep Texas wild.

Wimberley Valley and northwestern Hays County, Texas

Hays County is full of homes, large and small, that seem hidden in a vast, wildlife-rich native forest of live oak and cedar. On the winds of change we may still hear whispers of our pioneer Texan love of the natural world.

Swim Beach at Blue Hole Park and Natural Area in Wimberley, Texas

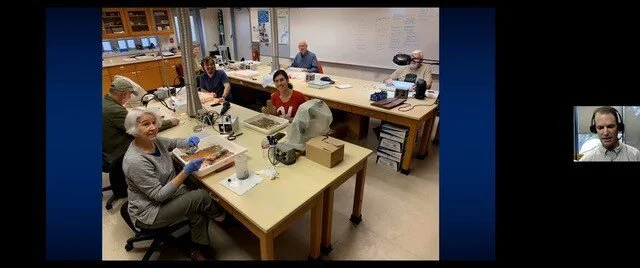

On a hot August 6, 2021, a team from the Hays County Master Naturalist education outreach program Wild About Nature (WAN) helped picnickers and swimmers at Wimberley’s Blue Hole get to know some members of local aquatic ecosystems. Our display wove trophic levels and food webs into encounters with Central Texas aquatic creatures. The exhibit offered kids and their parents hands-on activities to acquaint them with freshwater mussels, turtles, frogs, and dragonflies.

Mussels—Starting near the bottom of the trophic pyramid, freshwater mussels are filter feeders, whose diet consists primarily of algae and detritus that they draw into their body cavity through a siphon that they extend outside their shell. Since they are filter feeders, mussels are good indicators of water and habitat quality; in fact, the City of Denton uses mussels in its water treatment facility to test the quality of the treated effluent! Visitors to our Blue Hole exhibit had the chance to sort shells based on their colorful common names, including:

Washboard—The largest of our Texas mussels, it can exceed 12” in length. Its name comes from its resemblance to the old-time corrugated metal washboards.

Lilliput—The smallest of our Texas freshwater mussels (as in Gulliver and the Lilliputians), it rarely tops 1-2” in length. The most common one in our area is an endemic called the Texas Lilliput.

Southern Mapleleaf—There are several mapleleaf species in the state, but they all have a lobed edge that somewhat resembles the outline of a maple leaf. They’re also noted for the bumpy pistules on the outside of the shell.

Pink Papershell—Unlike the washboard and mapleleaf, which are sometimes harvested for the use of their heavy shells in the cultured pearl industry, the pink papershell is a fast-growing, thin-shelled species that can survive in softer sediments. True to its name, it has a lovely pink nacre, “mother of pearl,” on the inside.

Turtles—As omnivores, turtles fit in the middle of a trophic pyramid, feeding on plant material, insects, mollusks, and small fish. The WAN exhibit gave visitors a chance to examine the shells of five species, and adults and children alike were amazed to see the fusion of the turtle vertebrae to the scutes (individual shield-shaped puzzle pieces) of the carapace (the upper shell)— dispelling the cartoon notion that turtles can escape from their shells!

Our featured Central Texas turtles were three species we commonly see in and near water—plus an exception: a fourth common and very popular turtle that is at home on the dry land.

Red-eared Slider and Texas River Cooter—These are two of the most common turtles one might see in Central Texas. Both have a flattened body form and are commonly seen basking on logs in rivers and streams. Basking refers to these ecothermic species’ sunning themselves—using the sun’s energy to raise their body temperature. Sliders may have gotten their name from their propensity to slide off into the water as we approach. Cooter is similar to the word for turtle, kuta, in many West African languages. Although their shells can be hard to differentiate, especially in older specimens, in living specimens red-eared sliders are identified by the red patch behind the eye, whereas Texas river cooters have a pattern of yellow stripes and swirls on the head.

Musk Turtle—These smaller aquatic turtles are equally as common but not as often seen, since they do not come out of the water to bask. Their shells are easy to identify, as the scutes of their plastron (bottom shell) are very reduced in size. Two local species include the Common Musk Turtle (a.k.a. “stinkpot”) with a rounded shell and the Razorback Musk Turtle with a keeled shell.

Ornate Box Turtle—Visitors to the turtle exhibit were challenged to identify one other local turtle, one that was not aquatic. Did you guess it? The very domed shell of Texas’ Ornate Box Turtle actually has a hinged plastron that can completely close up, giving these turtles of the woodlands and prairies their name. Another term you may have heard is "terrapin." In North America, the terrapin is a handsome mid-sized spotted turtle found in brackish water—the diamondback terrapin. Yep, now you can talk Texas turtle, tortoise, and terrapin too!

Frogs—While the larvae of most frogs are primary consumers in food webs, feeding on algae and other aquatic vegetation, the adults are strictly predators, capturing insects with their sticky tongues—although bullfrogs will swallow small vertebrates! Visitors flocked to the anuran (frog) section of the WAN display, drawn by an exhibit that featured a recorded frog symphony and various materials, such as rubber bands, balloons, and marbles, that allowed students to mimic the nocturnal breeding calls of frogs and toads. By a strange quirk of acoustics, even ‘way out at the far end of Blue Hole lawn, amorous frogs and toads seemed to be advancing from all directions! We also offered a touch exhibit that used a pickled egg to demonstrate the permeability (and environmental sensitivity) of frog skin.

In clear plastic containers, our display of live frogs had been captured at a neighborhood pond in Wimberley the night before and, we reassured one earnest little boy, would be returned there right after this gig! They were four common local species:

Cope’s Gray Treefrog—This perfect mimic of lichens or tree bark lives up to its name, using the expanded pads on the ends of its toes to climb trees in woodlands near ponds and along streams. It may call its short trill from the trees or from the water’s edge.

Our captured specimen put on a nice display of its climbing ability, striding straight up its plastic container wall and allowing visitors to glimpse the bright yellow underside of its legs—a cool distraction coloration it can use to escape predators.

Gulf coast toad—This bumpy anuran with the light stripe down its back and prominent crests on its head is the most common toad in Central Texas. Famous for noisy choruses composed of long rattly trills, this species breeds in large numbers after the first rains of spring. About five weeks after those noisy nights, observant naturalists will find the ground full of small dark toadlets fresh from metamorphosis. We were able to display a tadpole and young toadlets of various sizes, along with an adult male with his distinctive yellow throat patch.

Blanchard’s Cricket Frog—These small members of the tree frog family may be the most common frog in Central Texas. Mottled in color and under 1.5” long, cricket frogs can commonly be encountered along the edges of local ponds and streams. From March through September they are more likely to be heard than seen. Children enjoyed mimicking their sounds by tapping two marbles together; when enough kids were tapping, it sounded exactly like an evening full of cricket frogs!

Dragonflies—Truly at the top of the trophic pyramid, these apex predators are renowned hunters. According to iNaturalist, 15 species in the order Odonata (the dragonflies and damselflies) have been confirmed from Hays County. Young visitors to the WAN exhibit were invited to try to capture prey with tweezers while looking through a kaleidoscope eyepiece designed to mimic the compound eyes of dragonflies and then encouraged to look for dragonflies during their swim activities.

After a brief rain shower, when picnickers had fled and swimmers were straggling out of the Park and just before we began packing up, an enormous electric blue damselfly—a male bluet like the one above—lighted on the corner of the dragonfly exhibit, teetered there for a moment, approved, and flew off into the afternoon.

Lee Ann Johnson Linam’s Texas A&M undergraduate degree in Wildlife Fisheries Sciences prepared her long career with Texas Parks and Wildlife. For J.D. Murphree Wildlife Management Area in Port Arthur, she was a waterfowl and wetlands biologist and Alligator Program Leader. While in graduate school in Australia, she actually protected Crocodile Dundee from crocodiles! Really.

In Austin, she was TPWD’s Endangered Species Program Leader and later developed Texas Nature Trackers, the Wildlife Division’s citizen science program, while also serving as advisor to the Hays County Chapter of Texas Master Naturalist™. Since retirement, Linam has taught science for home school and developed a unique Texas Wildlife Ecology course for secondary school students. A borderless science educator, she continues developing environmental education programs from Zimbabwe to Texas.

Blanco River looking upstream from the Fischer Store road bridge. Special thanks to Susan Evans for her help on this article.

I considered writing an article on the Blanco River shortly after Betsy and I took over The Hays Humm. I was new to finding topics every month, so the Blanco River seemed to be obvious. However, I was worried that, because the river is so familiar to many in Wimberley and Hays County, there would be little interest. Also, since access to most of the Blanco is on private land, I had few opportunities to see and explore it. Although the Blanco River flows 87 miles through the Texas Hill County, I wanted to find a small interesting stretch of the river in Hays County for my article. I found what I was looking for on the upper Blanco River segment in the northwestern part of Hays County. The area includes the stretch from the Little Blanco River entry to Saunders Swallet. Check out the map below to see to see how this area fits into the Wimberley Valley. This “loosing” segment is best known for its river water entering the underlying bedrock, filling the near-surface aquifers. The reality is that during low rainfall months the Blanco River is hardly flowing at all. It is reduced to a series of pools, each one fed by one or more springs. This results in dry river stretches between the springs.

BLANCO RIVER: The Blanco rises from springs three miles south of the Gillespie county line in northeastern Kendall County and flows southeast for eighty-seven miles through the Hill Country counties of Blanco and Hays to its mouth on the San Marcos River, inside the San Marcos city limits. The Blanco is part of the Guadalupe River basin and has a drainage area of over 400 square miles. The terrain features stairstep limestone benches and moderate to high slopes, surfaced by dark, calcareous stony clays and clay loams that support oak, juniper, mesquite, and grasses in the surrounding area and water-tolerant hardwoods and conifers along the riverbed.

Laurie E. Jasinski — General Entry Texas State Historical Association—Handbook of Texas

Upper Blanco River

A river pool is created a by large spring flowing from the underground Cow Creek Limestone (a.k.a. Middle Trinity Aquifer).

Karst cave in the outcrop immediately above the Upper Blanco River spring

The cave was created along a fracture and is also the source of a small spring. The limestone is in the Lower Glen Rose formation and is the upper part of the Middle Trinity aquifer.

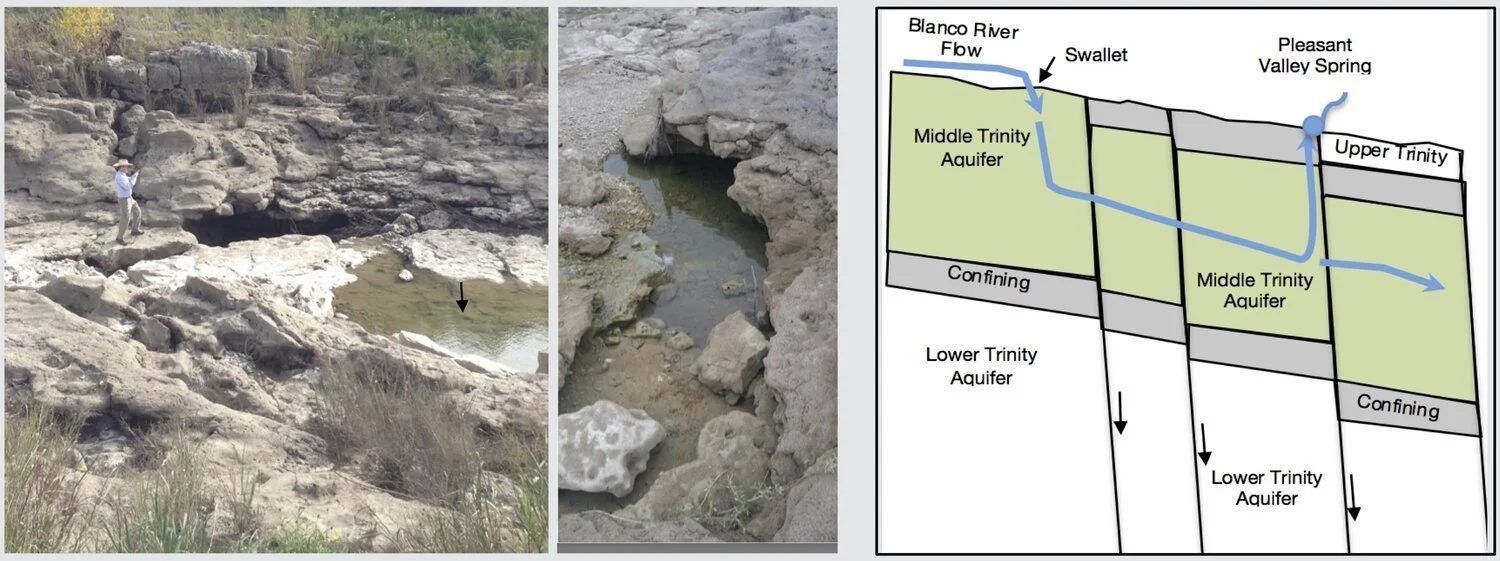

So where does the Blanco water go in these dry stretches? It easily flows underground, draining into the numerous sinkholes, faults, and fractures in the limestone. In this section, the Cow Creek limestone appears at the surface and can be observed in the bottom right photo below. The water enters the Cow Creek limestone, a significant formation within the Middle Trinity Aquifer. This same aquifer is the source for many of the iconic springs in the Wimberley area and also for Wimberley's drinking water.

View of the Upper Blanco River flood plain and valley in northwest Hays County

The spring-fed pool can be seen as a brown patch at the bottom of the photograph.

Dry Blanco River at low water crossing downstream of the large pool.

You can see the top of the Cow Creek limestone in the riverbed. The river is dry in this stretch because the water has flowed into the bedrock via karst features, such as sinkholes and fractures.

Saunders Swallet is a vital karst feature in the upper Blanco River. It’s an easy path for water entry into the Middle Trinity aquifer. The water seems to disappear from the surface. Groundwater moves through the aquifer, returning some of its flow to the downstream Blanco River at Pleasant Valley Springs (PVS). The remainder of the water continues to flow through the aquifer towards San Marcos, ultimately providing recharge to the famous Edwards Aquifer.

Karst recharge features. Saunders Swallet (sinkhole) is within the Cow Creek Limestone and located in the Blanco River.

Ref: Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District: Karst Systems of Hays County and the Edwards and Trinity Aquifers

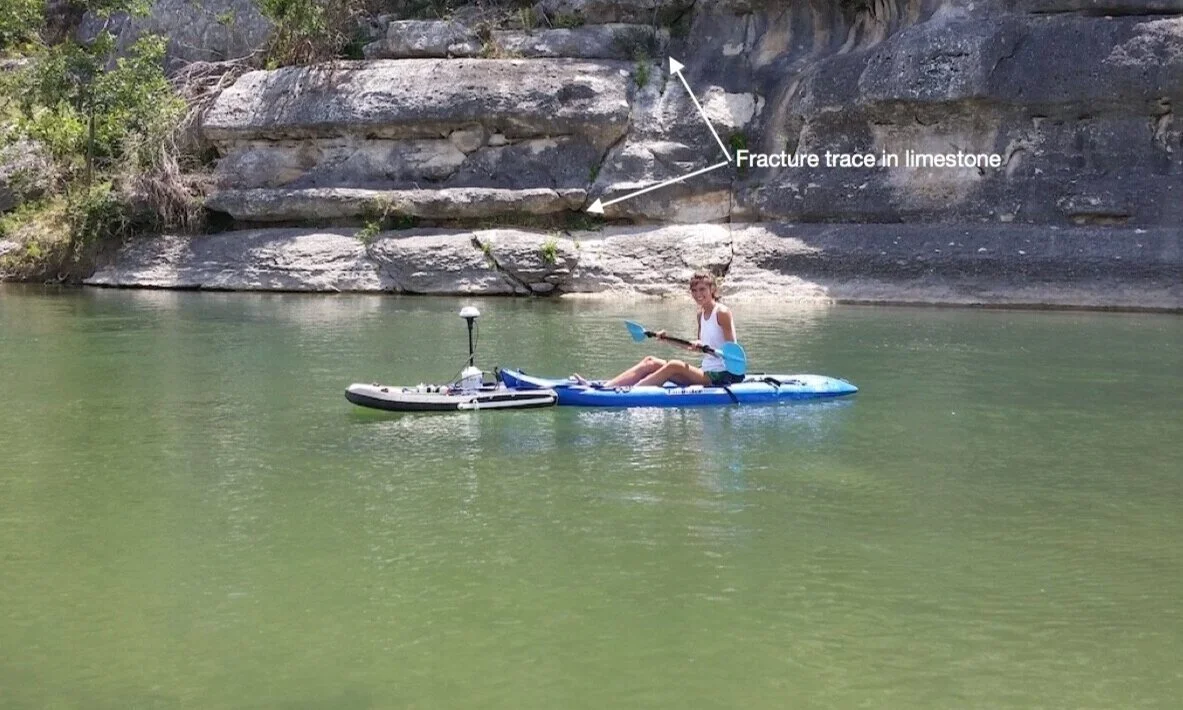

PVS is a perennial, artesian, karst spring complex located in the bed of the Blanco River near Fischer Store, Texas. Springflow issues from three sets of NW-trending fractures along a 450-ft. reach of the river. This accounts for 69% to 34% of baseflow, measured at the downstream USGS Blanco River (Wimberley) gauge. PVS is the largest documented spring of the Hill Country Trinity Aquifer system. Decreasing baseflows in the Blanco River over the past few decades suggest that the PVS is also decreasing over time, and it is threatened due to the combined effects of drought and groundwater pumping. Decreasing baseflows will impact the ecology of the Hill Country, flow in the Blanco River, and recharge to the Edwards Aquifer under drought conditions. Excerpt from The Geological Society of America, paper no. 39-3.

Pleasant Valley Spring — Kendall Yates, Research Assistant with the Edwards Aquifer Authority, measuring the flows at PVS. In the background you can see the fracture associated with the spring on the rock outcrop.

Little Blanco River: The FM 32 to Blanco River stretch of the Little Blanco River is 6 miles long and has been determined by American Whitewater to be a class II-III section, but only after a significant rain event. Similarly to the Blanco River, the Little Blanco is dry for most of this stretch. The Little Blanco is one of two tributaries to the Blanco River. The other one is Cypress Creek. Neither of these creeks contributes significant water to the Blanco. At its intersection with Highway 32, there is a very nice spring and pool that is wet most of the year. I took this photo a couple of years ago in March with the setting sun. It offers a great view of this beautiful section of the Little Blanco River. It is well worth a click to enlarge and view.

Thank You Contributors

Roger Allen, Mimi Cavender, Lee Ann Linam, Dick McBride, Steve Wilder

“We started the Hays County Master Naturalist Chapter in 1998, with the first class graduating in 1999. And after all these years, we have finally received our Charter.”—Susan Neill, President

Project Coordinators made brief pitches to recruit participants for their projects.

Listen again here to learn more details about the following volunteer opportunities.

Susan Neill: Project 401—HCMN Administration Opportunity—Become a Board Member or a Committee Chair or Member!

Cindy Cassidy: Project 1108—Hays County Friends of the Night Sky—Be an Influencer, become a leader, spread the word, make more stars!

Bonnie Tull: Project 702—Bluebird Nest Monitoring Project 702—Monitor bluebird nest boxes with a partner or individually!

Jo Ellen Korthals: Project 407—Meadows Center/Spring Lake—Prune, lop, plant native plants, and remove non-natives at the Demonstration Gardens & Wetlands Boardwalk!

Katherine Schmidt for John Montez: Project 2101—City of Buda Parks—Start September 18 on our first day of this project removing invasives!

Mike Meves and Mimi Cavender: Project 1010—Charro Ranch Park—Maintain trails, clear weeds, and plant natives on the second Saturday of every month!

Chris Middleton: Project 806—Site Visits and Project 704—Outreach—Become part of the Habitat Enhancing Land Management (HELM) Team or join the Wild About Nature Outreach Team!

Minnette Marr: Project 406—LBJ Wildflower Center—Help us find and conserve populations of the Bracted Twistflower!

Martha Pinto: Project 2102—Kyle Parks & Recreation—Join us to lead hikes and educational activities, improve the land, and much more!

Connie Boltz: Project 1902—Dripping Springs Ranch Park—Beginning Saturday, October 2, help to develop a National Wildlife Federation certified Wildlife Habitat!

Beverly Gordon & Lindsey Loftin: Project 913—Westcave Preserve—Volunteer for educational and conservation programs, greet visitors, become a docent!

Dean Lalich: Project 1701—Gault School of Archeological Research and Project 1904—Center for Archaeological Studies—Be a research volunteer in the field with digs or in the lab!

Gordon Linam, TPWD Chapter Adviser 2014-2021, was recognized for his service to our chapter.

Guest speaker Craig Bonds, Inland Fisheries Division Director, Texas Parks & Wildlife, spoke on Aligning Natural Resource Management Needs with Citizen Scientist Partners.

The birds quit coming…

Neeta purchased a couple of bird feeders to attract birds to the yard soon after our move to Buda, Texas, in April 2019. We attracted black-crested titmice (Baeolophus atricristatus), Carolina chickadees (Poecile carolinensis), house finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), northern cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis), and others. Next came a large group of lesser goldfinches (Spinus psaltria), which would at times cover all six perches of the niger seed (Guizotia abyssinica) feeder. The birds took turns eating while others served as sentries for protection. When we added bark butter and a suet feeder nearby, we attracted blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata), ladder-backed woodpeckers (Picoides scalaris), and red-bellied woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus), which we affectionately refer to as “chuck chuck.” Bewick’s wrens (Thryomanes bewickii), Carolina wrens (Thryothorus ludovicianus), and white-winged doves (Zenaida asiatica) also visited. All was going swimmingly until the fox squirrels (Sciurus niger) decided to drop in.

Birds are not tidy in their eating habits. The black-crested titmouse discarded seeds until it found one it liked. The chickadee followed much the same routine. They would take their fare up into the canopy to break open the shell and eat the contents before returning to the feeder. The cardinal, with its heavy beak, could eat straight from the feeder. The fox squirrels knocked seeds out of the squirrel resistant feeder by jumping onto it and attempting to lift the mechanism that closed the feeder while they hung on it. White-winged doves helped the squirrels comb through the discarded seeds.

Eating lunch on the backyard patio gave us a front row seat to these machinations except when heat, cold, and windy rain made being outside undesirable. Neeta added a hummingbird feeder to the feeder collection during migration season, and the black-chinned hummingbirds (Archilochus alexandri) came faithfully and fed when the flowers did not have sufficient nectar. She put about a cup of sugar water in the feeder and changed it about every 3 days, cleaning it well, when the hummers were humming. Most days I heard the whirring of the hummer wings more often than I saw them.

The fox squirrels became more brazen over time and would jump from the tree to the feeder. Putting up barriers between the tree and the feeder worked only a very short while. The fox squirrels turned out to be great problem solvers. No matter how entertaining their antics became, we wanted them gone. So Neeta began to add cayenne pepper (Capsicum annuum) to the bird seed mix to repel squirrels as was suggested in an article she read. So things were going along swimmingly once again. The birds seemed happy, and the squirrels showed up infrequently to gather up the fallen seeds that had been washed with rain or the water sprinkler. Fox squirrels aside, all this feeder intrigue was normal.

Then nothing!

The feeders were put out the same as always during the early spring of 2021, but no birds came except for the hummingbird. Even the fox squirrels did not visit. But then, in late May or early June, we noticed new residents. A pair of red-shouldered hawks (Buteo lineatus) had built a nest up in the tree canopy above our fence. We shared the mess of bird droppings with our neighbor. The presence of the hawks explained why we had not been seeing the birds and the squirrels. They had built their nest sometime between March and April and now had a juvenile in the nest. We had seen only one chick by late June, but there may have been another.

We didn’t monitor the nest on a regular basis, so we didn’t often see the adult pair. Red-shouldered hawks feed on small birds and mammals. Anytime a hawk or other raptor would fly over our neighborhood, the canopy would go quiet. Almost nothing moved or made a sound. This behavior only became more extreme when the hawks built their nest here. Our black-chinned hummingbirds were not worth the energy expended by the hawk to capture them.

The leaves and limbs in the canopy made it difficult to see the nest even when you knew where to look. I first spotted the nest with a juvenile still in it and took a photo of the fledging, which was barely recognizable; sticks in the nest obscured most of the face.

A few days later, the juvenile perched on a limb not far from the nest. What drew my attention to the young hawk was a loud clamoring from several other birds. When I investigated the commotion that was disturbing my lunch, I looked to a branch in the canopy and saw the subject of the commotion smack dab in the middle of it. This juvenile hawk did not move to strike back or in any way confront these smaller yet quite noisy birds, and they finally quit.

I retrieved my camera, tripod, and remote shutter release in hopes the juvenile would still be perched on the branch and I could get a decent photo. The young hawk remained perched long enough for me to get a decent picture.

The hawk takes one of its first flights away from the nest.

Neeta and I kept hearing a high-pitched bird call at frequent but irregular intervals. I had the camera focused on the juvenile when it cried out. The parents could not be seen from where we were, and I snapped a photo when the young hawk made the sound. Before long the fledgling flew a short distance and took up another perch, then flew a little farther and took another perch. More short flights were followed by a longer flight to the front of the house. I did not see it afterwards, and I did not go looking for it.

Red-shouldered hawk pairs mate for life and reuse existing nests. We will find out if we have a long-term resident in the canopy of cedar elm and live oak trees around our house.

In recent days we have seen only a few of the birds that used to come to the bird feeder. A few brave souls come to feed when the hawk does not appear to be close. These visits, except from the hummer, are infrequent and short lived. Birds are more skittish and vigilant when they do come and only take one or two seeds before retreating into the canopy. They can be seen flying throughout the canopy, but their songs are heard infrequently. We have not seen any hawks during the last days of July, but we suspect they have not travelled far.

Photos by Roger K. Allen