The HAYS HUMM - October 2018

TOM JONES & BETSY CROSS

Cover photo by Eva Frost

Roxana Donegan

About Myself: I was born in Bakersfield, CA and completed my education there with a BA in Education from Fresno State. I expected to spend my life teaching school, raising a family, and tending my garden. Instead I became a gypsy! My husband and I moved 14 times in 16 years, spending four of those years on Oahu, Hawaii. I also lived on a sailboat for four years before jumping ship to Antigua where I lived three years. After returning to Northern CA, I ended up in Napa where I volunteered and gardened for 17 years and was a partner in a yarn store. I moved to Wimberley in 2011, becoming a MN in 2013. I have volunteered in various areas, but really enjoy being on the Host Committee with Mary Dow Ross using my love of cooking once a month.

You May Not Know: While living on a boat, we had close calls with three hurricanes, and while in Antigua, I went through Hugo. Give me an earthquake any day!

FAV MN Activity: Participating in Cages for Classrooms and the Butterfly Festival at EAT&G.

Bird I Identify With: Chickens!

Eva Frost

About Myself: I am, originally, from Los Angeles, but was only there while Dad was in the Marines. Our hearts and families were in Austin, Texas, and returned in the 70's. We quickly moved to Dripping Springs, across from Nutty Brown when Hwy 290 was two lanes. I have worked as a surface mount technician, personal assistant, caregiver and am currently an assistant electrical estimator at Westar Electric Co. Most importantly, I am a proud volunteer of the Texas Master Naturalists in Hays county. Certified Texas Monarch of 2014.

You May Not Know: I have enjoyed all things nature, since I was a young child. My mom always jokes that my friends were all bugs. My grandmother made me a flower necklace out of Lantana and it really affected my views profoundly. Adventurous and love to hike all over! I became a photographer and avid birder about five years ago and spend a lot of time studying them. I saw a bird with vertical lines on his face and had to find out what that was! So, the American Kestrel falcon was my first bird to ID and still one of my favorites. I have loved to watch the Scissortail Flycatchers since I was a kid. I am learning to bird by ear and have found some rare visitors.

FAV MN Activity: I have really enjoyed working at Westcave and doing vegetation surveys at Lady Bird Johnson's Wildflower Center. I work on Project Feeder Watch at two sites and am now certified in Water Quality Monitoring, Water Stewardship and just recently, TX Waters program. My interests are getting involved in water protection and monitoring in Hays County. Long term, I would like to be in a restoration project and more involved in Land Stewardship and water catchments.

Bird I Identify With: Maybe a raven, because I talk too much, like to goof off and love a challenging adventure!

Checkered Setwing (Male, Red-faced)

Checkered Setwing (Female)

Dragonflies were the first winged insect to evolve 300 million years ago. Their four wings are 2-5 inches long now, but back then, they were 2-4 feet long. Meganeura, a genus of extinct insects from the Carboniferous Era, was the largest insect known. It is believed that the high oxygen levels in the Paleozoic, until the end of the Permian Era, attributed to their large size. Dragonflies evolved from this creature. Some nicknames for dragonflies include snake doctor, devil's darning needle, spindle, ear sewer and my favorite, the skeeter hawk.

Females leave eggs in waterways or swampy waters. Even if she dies, her eggs will still survive, hatch in the water, and become predators of anything they can eat. They are called naiads. They have a voracious appetite and will even eat small fish and other naiads. They do this for about a year or two.

They shed a few times before the larvae, or naiads, climb up on a stick and shed their exoskeleton. This could happen quickly, or it could take an hour or longer. Then the new "teneral" dragonfly hangs, sometimes for another hour, or longer. This is a time for "pumping up", leaving them in a very vulnerable state. Some adults live a few weeks, some a few years. You can usually find little exoskeletons going up the sticks in the water.

Amberwing with Exoskeletons at Launch Pole

Dragonflies have to reach a temperature of 63 degrees to get moving. And these voracious eaters can only eat when they are flying, which they are extremely good at. They literally consume everything, including other dragonflies. On a good note, one dragonfly can put away 30 to hundreds of mosquitoes in a day. They have a small "arm" hanging by their mouth to assist in holding the prey or cleaning the face. Its head is all eyes, and they have 360-degree vision, which begs the question, "Why are they always flipping their head back and forth?" Actually, a dragonfly can pick one individual flying insect from a group of flying insects and calculate its speed and trajectory to catch that exact fly. So, I guess it's doing math!

Four-spotted Pennant - Oblisking

Hundreds of different species will gather for feeding or migrating in the early morning on a freshly mown, wet yard or near a swampy area or water catchment. They do like it hot, too, so in the afternoon, they are found perched at the tip of bare sticks or the points of a century plant. Agaritas, Red Yucca's and the tops of trees are good perches. They regulate their body temperature by abdomen oblisking.

Dragonflies and damselflies are in the Order Odonata, from the Greek meaning "the toothed one". Dragonflies are in the infraorder Anisoptera. The damselfly is from the Zygoptera. You can tell them apart, because the damselflies are smaller and sit with wings folded up. They seem to have two large, separate eyes. Damselflies, also, will sit on a rock or stick for a while, as dragonflies are more on the move. Their presence is the sign of a healthy ecosystem and clean waters!

Bluet Duet

THE MASTER NATURALIST LOGO

Information on Logo provided by Michelle Haggerty - Texas Master Naturalist

The Cyrano Darner was chosen as the Master Naturalist program logo for many reasons. First, dragonflies in general are beautiful, interesting creatures. They are widely distributed and accessible and even the most urban of urbanites are likely to have seen them “in person”. The size of the dragonfly made it easy to use in a logo and the darner family has the most classic dragonfly shape with the Cyrano darner having the most beautiful coloration especially in the male. A cruiser may have also worked, but the Cyrano was the most beautiful we thought. The beauty of the detail, the structure and the venation of the wings in the Cyrano Darner made it very appropriate for capturing the “19th Century naturalist’s field notebook look we were trying to achieve with the logo. The idea of capturing that much detail in a creature that small says a lot about not only love of nature but also the a value for scientific accuracy. Forrest Mitchell’s Digital Dragonfly Museum (http://www.dragonflies.org) inspired us early on because most of the specimens were collected by Forrest and his assistants. We wanted the logo to be an actual species and not just a pretty drawing. The Digital Dragonfly Museum specimens were captured and refrigerated to make them dormant and then scanned using a flatbed scanner and a mouse pad with a hole cut in it to keep from crushing the specimen. The scanning helped re-warm the specimen and when it was done the original was released unharmed. That shoestring creativity to capture accurate images (avoiding the loss of color that happens when you kill a specimen) and meticulous attention to detail seemed like a great attainable example of what a naturalist does. When the program was implemented statewide in 1998 we chose the Cyrano Darner as the program logo from several other species drawings which are also represented in the program today. At the time, we wanted a logo that wouldn’t be confused with those of other nature organizations and since dragonflies were not yet seen very often in logos--unlike oak leaves, horned lizards, bluebonnets and other emblems of Texas flora and fauna--we chose it. Of course dragonflies are everywhere now, but who knew?!?

THE DRAGON-FLY (1833)

BY ALFRED LORD TENNYSON

Today I saw the dragon-fly

Come from the wells where he did lie.

An inner impulse rent the veil.

Of his old husk from head to tail

Came out clear plates of sapphire mail.

He dried his wings: like gauze they grew;

Thro’ crofts and pastures wet with dew.

A living flash of light he flew.

EVA FROST DRAGONFLY GALLERY

The Devil’s Backbone

Article and Photos by Tom Jones

Click on photos & graphics to enlarge and view in Lightbox

The Devil’s Backbone is one of the most scenic drives in Comal and Hays Counties. It is a five-mile stretch along Ranch Road 32 just inside the Comal Co. line. The road is on top of a narrow ridge which has an elevation of 1,225 feet and offers unparalleled views of rolling ranch land. I can remember the first time I visited the Devil’s Backbone. It was in my junior year of college at UT working on a Geology degree. One requirement was a multi-week field trip introducing us to the geology of Central Texas. Later, I returned to the Devil’s Backbone to accompany my son to El Rancho Cima Boy Scout camp on the Blanco River. I will never forget the thrill of backpacking with him up to the summit of Sentinel Peak, camping overnight and gazing at the incredible stars.

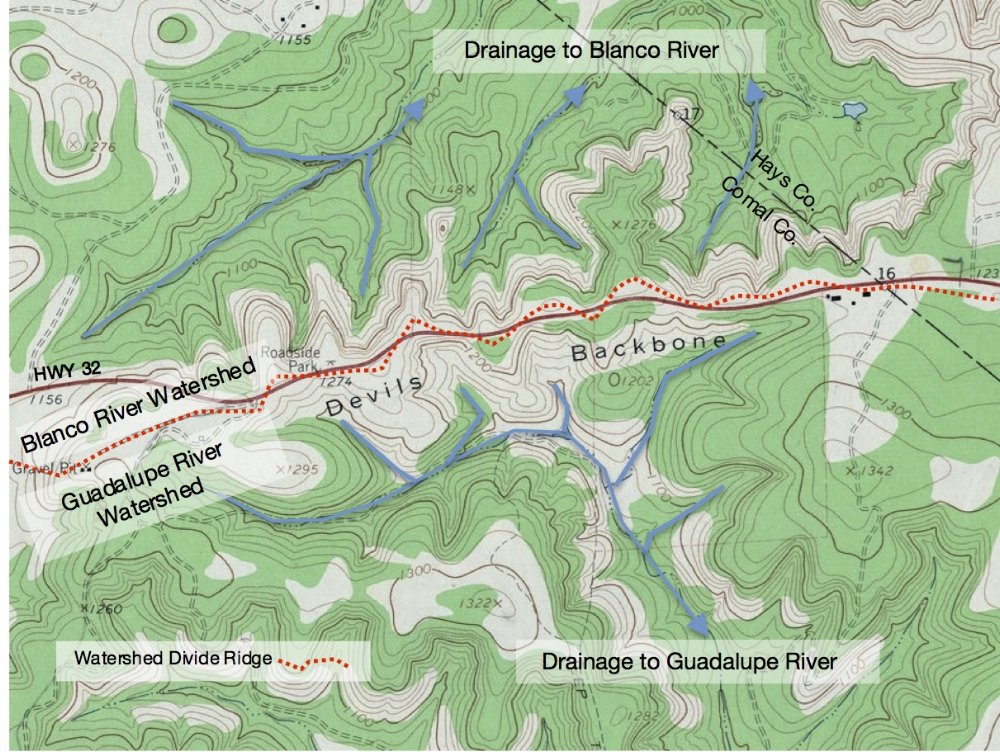

The Devil's Backbone was created by erosion of the Edwards Plateau as the adjacent Guadalupe and Blanco Rivers became entrenched forming their respective watersheds. One feature of watershed anatomy is known as a watershed divide. However it is more commonly referred to as a ridgeline, which separates neighboring watersheds. On rugged land such as the Devil's Backbone, the divide lies along an elevated ridge. The ridgeline is narrow allowing great views on either side of RR 32. The topographic map graphic illustrates the location of the watershed divide in relation of RR 32 and its impact on drainage patterns near the Devil's Backbone. Rainfall runoff on the Devil’s Backbone feeds into the Blanco or Guadalupe Rivers, depending upon which side of the watershed divide it falls on.

Looking out from the Devil's Backbone you can see deeply carved valleys and rounded hills, which are much-loved features in the Texas Hill Country. What caused this narrow strip of land to stand tall while each side is eroded away? Typically, ridgelines are composed of rock that is harder and better cemented allowing it to withstand the erosive forces of water and wind. Also ridgelines may have fewer fractures or cracks which can create weakness within the rock layers.

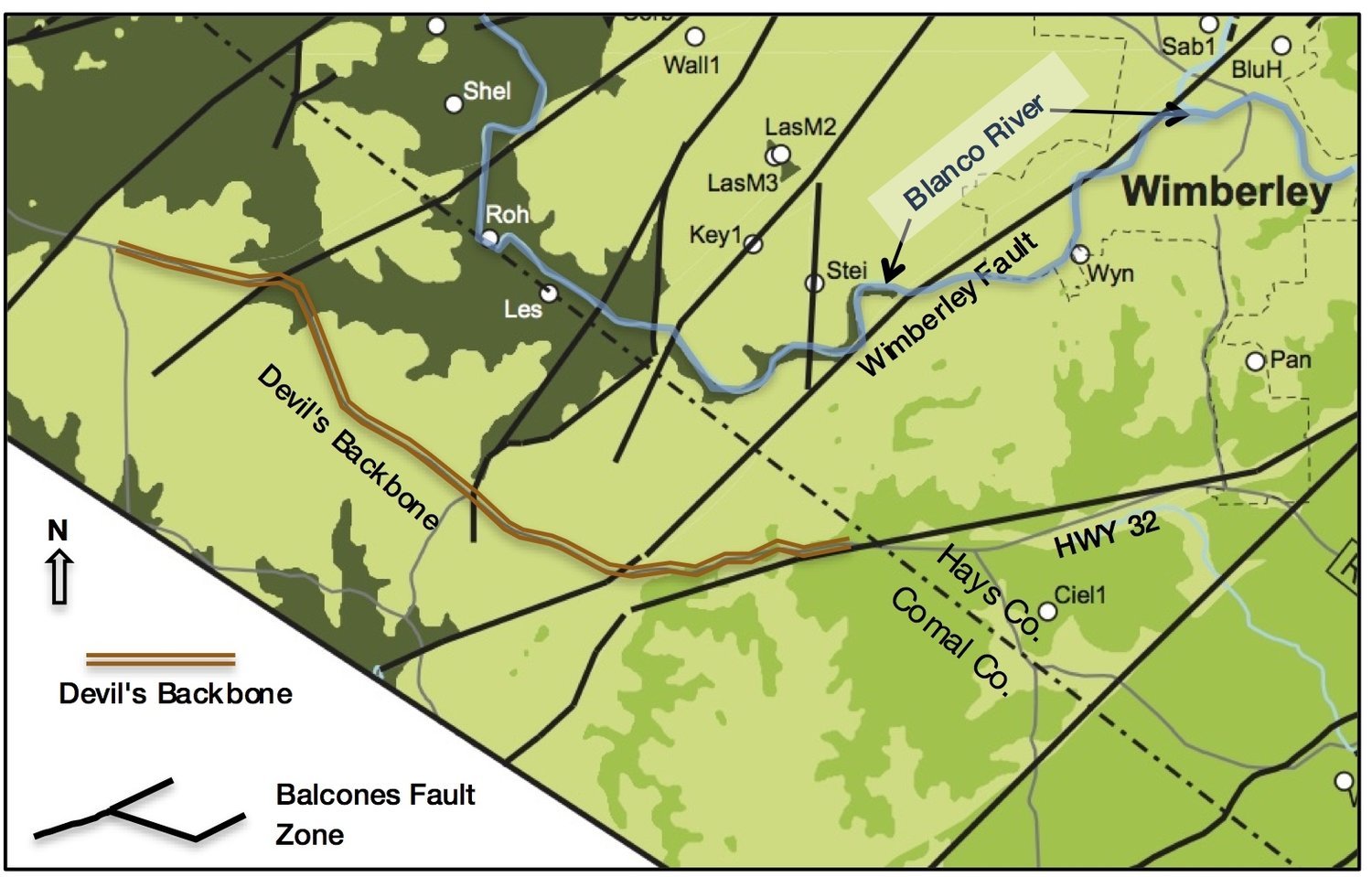

Geologic Base Map - reference: Hydrogeologic Atlas of the Hill Country Trinity Aquifer, Wierman, Broun & Hunt, July 2010

Devil’s Backbone Topographic Map

Although the Devil's Backbone is in Comal Co., the best views are of the Blanco River valley to the north looking into Hays Co. Illustrated on the geologic map are many black lines marking the surface locations of faults, which are collectively part of the Balcones Fault System. Faults are simply fractures in the rock accompanied by movement of the limestone formations relative each side. The faults were created during the the uplift of the Edwards Plateau.

The deep Blanco River valley is easily seen from the top of the Devil's Backbone, as it is flows southeast in close proximity and parallel to the Devil's Backbone. Take a look at the geologic map and note that the direction of the Blanco River suddenly makes a sharp left turn, changing its course to the northeast away from the ridge toward the City of Wimberley. The abrupt change in the flow direction is caused by the river intersecting a major fault line locally referred to as the Wimberley Fault. The river path then closely follows the fault to downtown Wimberley. Cypress Creek at the Blue Hole is also aligned along this same fault.

Faults have a big regional influence on ground water by creating pathways for rainfall to enter formations at the surface and recharge the deeper Trinity aquifers. A little closer to San Marcos this fault system has the same impact on the Edwards aquifer. In fact, roadside signs along the Devil’s Backbone provide notification when you are entering the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone. When you see one, you can be sure that the Balcones Fault System is nearby. The other local impact is that the faults allow deep underground aquifers a pathway for water to flow to the surface, creating springs. Great examples include Spring Lake, Barton Springs and the springs along the Comal River. I also believe that the springs at Blue Hole are related to groundwater movement up the Wimberley Fault.

The Devils’s Backbone lives up to it name based upon stories and lore reported about this area.

“Comanche and Kiowa used the Devil’s Backbone to spot and monitor settlers who were moving into their territory. The Indians’ ghosts are said to still roam the area, with hikers, hunters and landowners frequently reporting an unseen presence following them. Bert M. Wall, who has lived on the Devil’s Backbone for nearly 35 years, had heard stories about a wolf spirit that would possess people, but he didn’t believe them until his son went exploring with friends nearly twenty years ago. That’s when one of the boys, John Villarreal, saw a vision of a wolf that caused him to slip into a trance. ‘He was totally out of it, ranting in a language that sounded like a mix of Spanish and Apache,’ says Wall, who suspects that the Indians were seeking vengeance for having been forced off their land. He’s also seen a Spanish monk on his porch and mysterious lights when he’s been out working cattle. ‘I’m convinced that old cowboys are checking up on us to see if we’re doing things right.’”

Like the Comanche and Kiowa before us, we also use the view from the Devil's Backbone to spot and monitor the progress of development from an increasing population moving into this beautiful hill country landscape. Living in Wimberley I cross the Devil's Backbone frequently. And every time I catch a glimpse of Sentinel Peak, the wonderful memory of camping with my son at El Rancho Cima returns.

The Snake and My Toes

More flotsam and jetsam from a Naturalist’s Mind

ARTICLE AND PHOTOS

BY SUN GATTO

Click on images to enlarge & view in Lightbox.

So I was sitting outside by the pond yesterday morning when I saw a frog literally hopping for his life across the patio, being chased by one of the resident ribbon snakes. He managed to escape into the water and under the lily pads, but the snake stayed around for a while. I got to watch him navigate his world for a couple of hours.

First, he tried to stalk what he thought was the frog, but it turned out to be just a blob of muck.

Next, he crawled up one of the plants and dangled himself over the water in a clear spot. I guess he figured the frog might swim by and he could make a quick ambush. Instead the koi wandered past, and after thinking maybe he could nab one of them - I could actually see him tighten up for a strike - he decided, nah, they were too big.

Then he decided to come check me out. He hadn’t been using his tongue prior to that, but I guess he had to smell me before deciding I also was TOO big. It took a bit of nerve for me to leave my feet by the rocks when he went under them to come out of the water. Why was that? I knew he was there. And I knew he wasn’t going to bother me. I mean, it was just a ribbon snake.

But snakes can do that to you, even to us Master Naturalists. What causes that innate instinctive reaction to potential threats? How can we still be hardwired to react after all these generations living away from the natural world? Can we overcome these fears when there is no longer a rational reason for them? Watch “The Babadook” to see if you still get scared by the boogeyman.

I once knew a girl who was so afraid of spiders that she ran away screaming when she saw one. I pointed out the potential to fall off a cliff, or get hit by the proverbial bus. Or that all the noise she was making might bring a real predator (lion?) around. She didn’t think I was funny.

I trained horses for over 20 years. Talk about a highly ingrained flight response to danger! Some of them will think a hose, or a piece of rope, or any long, thin, unnatural looking thing on the ground just might be a snake. You better hang on when that flight response kicks into high gear.

Even my koi understand innate dangers. They won’t come up to feed when the shadows are just right. They must think I look like a GREAT BIG heron standing over the pond. Of course, for them, that is a real ongoing threat. Many a koi in a backyard have been eaten by a heron. Just not a 5’6” one.

I guess innate fear must be part of our DNA. And even when created by unnatural circumstances, it stays with us. Like the caterpillars trained to avoid a certain odor retain that aversion even after metamorphosis. Link: http://theconversation.com/despite-metamorphosis-moths-hold-on-to-memories-from-their-days-as-a-caterpillar-29859

But horses can be trained to confront their fears. Think of the movie “War Horse”. Read “Elephant Company: The Inspiring Story of an Unlikely Hero and the Animals Who Helped Him Save Lives in World War II” to learn about elephants trained to do almost impossible feats in spite of their understanding of danger. But maybe just confronting fear isn’t enough. Imagine if ALL the soldiers ran away at the first battle. Or maybe it is keeping your toes by the rocks, even when you don’t know exactly where that snake will come out.

Of course, my ability to do that was really a result of knowing what kind of snake I was looking at, what that snake’s place in the natural world was, and how it intersected with mine. It was all that knowledge that allowed me to keep my feet firmly planted on the ground. In other words, it was because I am a Master Naturalist!!! And the snake, in spite of his missing out this time, is a darn good hunter. I hardly ever have any frogs in the pond anymore.

“Courage is a special kind of knowledge; the knowledge of how to fear what ought to be feared and how not to fear what ought not to be feared.”

2018 Training Class SV #4

San Marcos, Texas

WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT & GEOLOGY WALK

Article and Photos by Andy Witkowski

Flint also know as Chert collected at property

Click on images to view in Lightbox.

On September 4th a group of about 25 Master Naturalists met on a 30 acre ranch Northwest of San Marcos to hear two presentations specific to the location. When the land was purchased 10 years ago it was, as is much of the hill country, overgrazed and stressed. The new owners were motivated to start the process of encouraging the reintroduction and reestablishment of native grasses and other plants. Blake Hendon, Wildlife Biologist with Texas Park and Wildlife, was on hand to walk the group through the pastures to discuss particular aspects of range management.

Blake Hendon holds up a Doveweed, One-Seed Croton and explains that it is a mid-early successional plant

Stocking rates were discussed in detail and how different sites, different government entities and different animals affect this number. Stocking rates or animal units are a critical calculation to folks who manage rangeland or pastures with animals.

Not only is this used in determining agricultural tax exemptions, but the understanding of allocating appropriate amounts of forage is an essential step in protecting the long term viability of your land. Essentially, based upon a 1,000 pound cow who needs about 3% of their body weight per day in forage, coupled with a “take half/leave half” strategy for sustainability, in an ideal Hill Country ranch there should be about 15 acres per cow.

Tom Jones works with members of the 2018 Master Naturalist class in identifying and talking about different pieces of flint and Karst Limestone encountered on the ranch walk

For landowners who find themselves in similar situations, with overgrazed rangeland he stressed that it is important that we understand the unique ecosystem and work to reduce the negatives and support the increasers as the natural process of succession occurs.

The next stop on the ranch walk involved our own Hays County Master Naturalist, Geologist Tom Jones discussing rocks and the history they tell. The property presented a unique place to discuss the geography of the hill country; sitting on an extension of the Balcones Fault, this stretch of Karst topography of the lower Edwards formation had numerous examples of flint, fossils, and what is believed to be an oyster reef.

Standing in the field where 100 million years ago was a shallow sea, remnants of life remain. Plankton and other sea living animals left their detritus and debris in the form of silica and calcium carbonate. From the early Cretaceous to Quaternary periods, deposits of sediments were happening simultaneously with the uplift of the continent which created the Gulf of Mexico and the Hill Country.

GENA FLEMING IBIS GALLERY

“I saw an Ibis at Spring Lake. I think it is a juvenile White Ibis. It looked like he joined another one after he flew away. The Ibis was not far away from a flock of great white egrets. I read that they would frequently be in the company of egrets when separated from other Ibis. I thought it might help in spotting the Ibis again, to look for it when there are egrets around.”

Better Lights for Starry Nights

HCMN Supporting Wimberley Dark Sky Event

September 30, 2018 Wimberley Community Center

Click image to view Gallery in Lightbox