Voices

Yellow-billed Cuckoo Photo: Betsy Cross

Mimi Cavender

I was a suburban San Antonian freshly retired to a wooded hillside south of Wimberley when I took a summer night’s walk down my road under startlingly starry skies. There was a thread of breeze and enough starlight to see some asphalt just beyond my feet. Grasses and fence lines, cedars and oak scrub were all deep, featureless, silent black. Out of that dark came a scream, a quick descending hoarse rasp with a brittle choke at the bottom. What do they say?—just back away?—and I did—but when the second scream followed, a little closer, I stood legs apart, arms in the air to look bigger, and growled back as viciously as I could. Then I turned and strode back up the hill, every body hair on end, knowing I’d be shredded by the neighborhood cougar.

Photo: Betsy Cross

Turns out mountain lions are improbable in this or any semi-rural Central Texas neighborhood. Since that adventure, I’ve enjoyed a Master Naturalist education and six years’ hearing voices in the Hill Country night. That was a fox calling to another, who screamed back. Mating behavior or domestic quarrel, it’s a hair raising sound. I saw a pair just yesterday in broad afternoon calling to each other across the width of my acre. But darkness makes these voices larger. Mysterious. Wonderful.

Beginning in mid-May, Texas Hill Country folks look forward to the arrival of two migrating bird species whose loud voices signal early summer: the Yellow-billed Cuckoo and the Chuck-will’s-widow. We hear them before we see them—in fact, many of us have never seen them. They’re both shy, they’re active at night, and they’re carnivores and so don’t come to our seed feeders. Photos of either of them are prized because it’s hard to catch them without good gear, skill, and patience. But oh, those voices! Let’s meet these two iconic—and noisy—summer visitors.

Photo: Betsy Cross

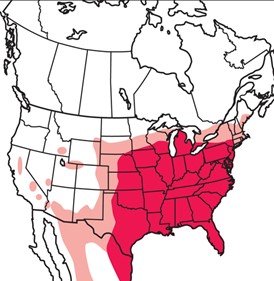

Yellow-billed Cuckoo in N. America

Red = current common breeding range

Pink = shrinking breeding range

The Yellow-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus of the family Cuculidae, which includes our Greater Roadrunner) is the most widely distributed of the three migrant cuckoo species breeding in the lower forty-eight states of North America; the other two are the Black-billed Cuckoo, across the upper Midwest—and the Mangrove Cuckoo, just hanging on by his two front toenails to Florida’s Gulf coastline. The Yellow-billed Cuckoo is still common in a broad range from Central Texas and across the South, the Central Plains to the Atlantic coast and north to Michigan and New York. They winter as far south as Argentina and begin migrating north in April each year to breed here. Central Texas’ mixed juniper/oak/cedar elm woods and riparian willow marshes suit them just fine.

Both sexes look the same: 12 inches long, sleek, cleanly-marked: warm grey top, white below, rufous primary wing feathers, a long tail with white oval spots along the undertail, a yellow eyering, and a curved beak with yellow mandible. In common with all cuculidae, they have two toes in front and two behind. Juveniles are similar to parents except for less clearly defined tail spots.

Photo: Betsy Cross

Yellow-billed Cuckoos are primarily carnivores. They prefer caterpillars, including hairy types such as tent caterpillars—yes, please!—and they time their arrival in breeding areas to coincide with late spring caterpillar abundance. They also eat other insects, such as cicadas, beetles, grasshoppers, and katydids; and they may eat some lizards, frogs, eggs of other birds, and small fruits. They’ll hunch down almost vulture-like on a high branch, long neck and curved beak stretched forward, anticipating passing prey. They don’t eat seeds and so won’t visit our feeders, but they will come to water features to drink and bathe. Somehow they manage to make it all seem elegant.

Savvy guy that he is, the male feeds the female when courting her. Losing no time, they both build the nest; it’s usually 4 to 10 feet (up to 20 feet) above the ground in a tree, shrub, or vine—a small, loose platform of twigs and stems, sparsely lined with grass or leaves. She lays 3 to 5 pale blue-green eggs (more in a caterpillar-heavy year). Both parents incubate during 9 to 11 days, and both parents feed during the week before the young climb out and onto the branches, continuing to be fed by their parents until they can fly after three more weeks.

Myth buster! While Old World cuckoos may occasionally lay their eggs in other birds’ nests (to allow the female cuckoo to have a second brood in that nesting season), this practice is now understood to be rare or absent in North America. The breeding behavior of these cuckoos would be fascinating to watch—if we could just find them! All we usually have of them is that unmistakable voice.

Audible at a great distance, Yellow-billed Cuckoos are heard on hot, humid afternoons and into the night. Throughout the South, before weather satellites and 7-day forecasts, tradition called this bird the “rain crow,” who—like our blooming Cenizo—was thought to predict rain. Listen to its “song,” the hollow knocking kuk-kuk-kuk, here. And its calls, the coo and kowp, here (Heads up: there’s a Northern Cardinal nearby!)

An alarm from Texas A&M University came as early as 1996:

Although it is still a fairly common bird in Texas, the Yellow-billed Cuckoo’s numbers are diminishing. Like many neo-tropical migrants, it has declined considerably throughout its range in the past thirty years (Sauer et al. 1996). It has shown a substantial decline in virtually all regions of the country. In Texas, BBS data indicate that it declined by a statistically significant 2% per year from 1966 to 1996 (Sauer et al. 1996).

Chuck-will’s-widow with chicks Photo: Dick Snell, American Bird Conservatory

Chuck-will’s-widow in N. America

Red = common breeding range

Pink = declining breeding range

Chuck-will’s-widow (Antrostomus carolinensis, family Caprimulgidae: Nighthawks, Nightjars) is the largest nightjar in North America. Its famous cousin, the Whip-poor-will (Caprimulgus vociferus), ranges the northeastern third of the United States and slightly into Canada, with our Chuck-will’s-widow overlapping the southern portion of that range to breed in central and east Texas and the entire South to the Atlantic coast. It winters in southern Florida but mostly in the West Indies, Mexico, Central America, and northern South America. It breeds in liveoak and pine woodlands, in grasses and understory, and in marshy areas.

Chuck-will’s-widow’s “cave-mouth” has stiff face bristles that help guide prey into its gaping mouth. Photo: Aaron Given, Kiawah Island [Florida] Banding Station

It’s 12 inches long and intricately marked with fine black spots and stripes on the buff brown body, a cream necklace above a black breast, and a short curved beak with stiff chin whiskers. Sexes look alike, except that the female’s tail lacks the male’s white secondary feathers. Its overall appearance offers good camouflage to this ground-nesting bird.

The Chuck-will’s-widow hunts at night, most actively at dusk and dawn and on moonlit nights. It flies out from a branch or from the ground to catch night-flying insects, especially beetles and moths, but it can take warblers, sparrows, and hummingbirds. It will also cruise along the edges of woods in continuous flight to capture prey in its wide gaping mouth, swallowing its food whole. Its Latin name, Antrostomus, means Cave-Mouth! Here’s a great little video featuring that huge mouth and an unnerving amount of singing.

If you’ve been sleepless from the non-stop calling of a Chuck-will’s-widow whistling his name all night, take some comfort in that you were hearing his mating song. No great poet, he just says his name—over and over and over. If successful, he sidles up to an arriving Mrs. Chuck, puffs up his plumage, spreads his tail, droops his wings, and moves jerkily, calling all the while. What Chuckess can resist? She’ll eventually lay her eggs in leaves flat on the ground, often returning to the same spot the following year. Far from finicky, these birds must be supremely confident in their camouflage.

The eggs are creamy white with brown and gray blotches (more camouflage for ground nesting). If the nest is disturbed, the adult may move the eggs some distance away. The 3-week incubation is probably by the female only, and hatchlings are apparently cared for by the female alone. She shelters them by day and feeds them by regurgitating insects. They’ll fly about 17 or more days after hatching. If all of this behavior sounds vague (“probably,” “apparently,” “about”…), it’s because this species is so camouflaged, nocturnal, and secretive. They merit serious research.

A closeup of the Chuck-will’s-widow’s specialized middle toe’s “comb,” thought to be for the bird’s grooming the rictal bristles (stiff, spine-like feathers around the mouth).

If only for insect control, these nightjars are valuable in the ecosystem. But their numbers are declining due to habitat fragmentation and to declining insect and frog populations, some of the first to succumb to the warmer, drier climate. Visit the Chuck-will’s-widow Audubon site to see the dynamic graphic projecting its future. And find more photos and information on The Cornell Lab of Ornithology All About Birds.

These two visiting summer birds, a cuckoo and a nightjar—both so famous across the eastern half of North America for their unforgettable voices—are pure nostalgia. They’re our childhood, summer evenings, moonlit nights. They’re the persistent soundtrack of our memory of the way the natural world is supposed to be—and can always be—if we can keep it.

A reminder! We’re in spring/summer migration. A lot more than cuckoos and nightjars are migrating into and over Texas every night. Our artificial light confuses them, interferes with their navigation, feeding, mating, nesting—endangers their lives, their species’ future. Be kind. Turn out all bright white and any unnecessary lights. Direct those lights you absolutely need toward inside or downward, or put them on a motion sensor. Then, with all of nature, enjoy the night! See what’s up this summer at International Dark-Sky Association and Friends of the Night Sky.

And to know what’s flying overhead in real time even as you’re reading this, check out the exciting new adventure at BirdCast! And here’s a quick BirdCast tutorial.