2023 HCMN Gala

HCMN Graduating Class and Chapter Awards Celebration

The River Cooters

Loren Steffy

How I became a River Cooter

The moment of inevitability washed over me like a slow-moving cold front. I would be a river cooter. Even though I was an aspiring Master Naturalist, I wasn’t sure what a river cooter was. My training mentor, David Womer, half-heartedly assured me it was a turtle and not a reference to my age.

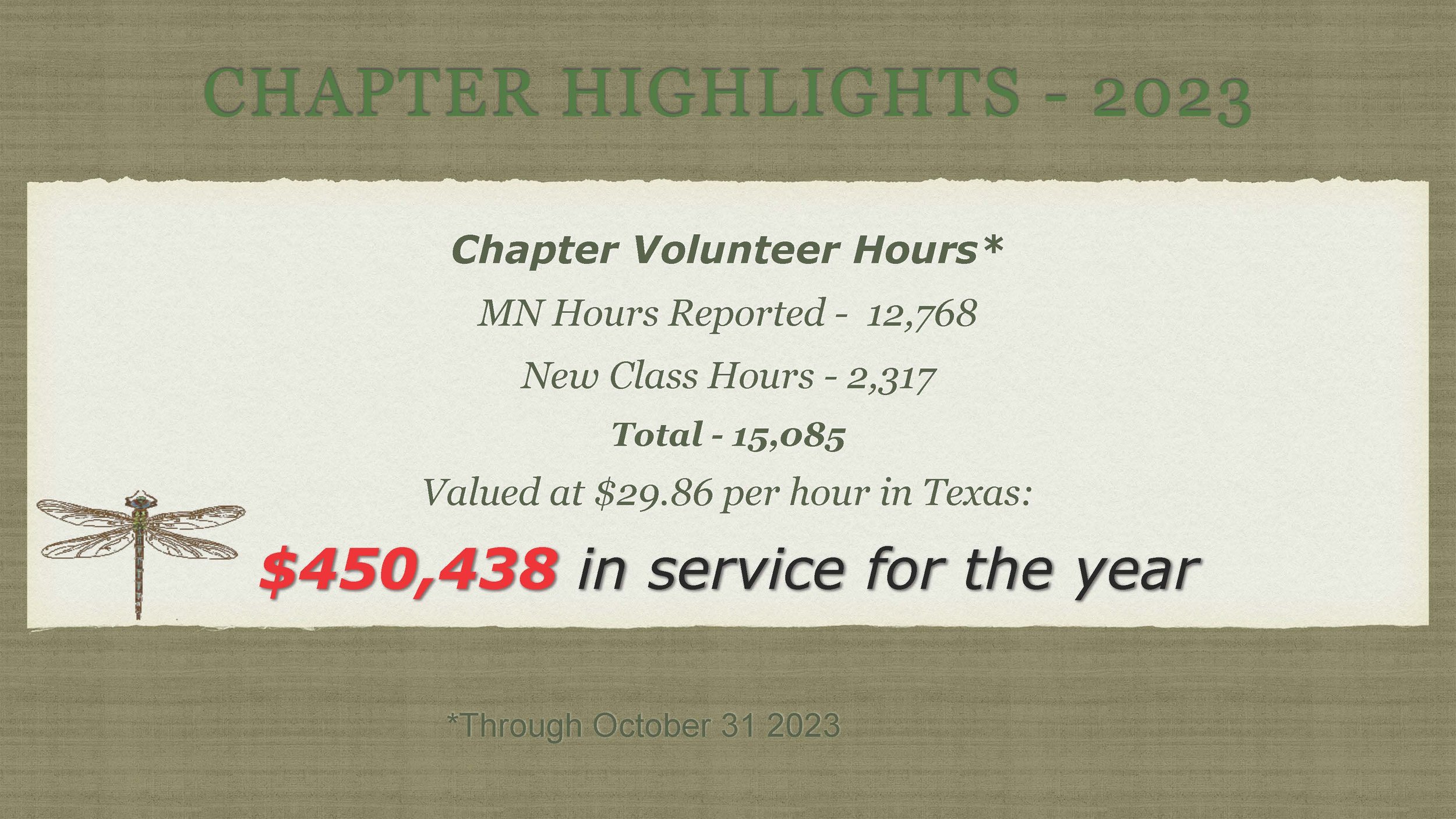

In fact, the 39 River Cooters—members of the Hays County Master Naturalist chapter’s 2023 graduating class—are a spry bunch. During the past 10 months, the River Cooters set new records for volunteer and advanced-training hours, clocking in at 2,410 and 728, respectively. Thirteen members—one-third of the class—double-certified.

Our group completed 12 three-hour class sessions that included outdoor training at John Knox Ranch in Fischer and the Meadows Center in San Marcos. All members also attended two or more two-hour site visits.

That tops last year’s class, the Caracaras, which logged 1,899 volunteer and 577 advanced-training hours. However, last year’s class included two graduates who were pregnant. We didn’t have any little river cooters this year, although the class had another unique distinction—three participants (including me) are married to other Master Naturalists.

So how did we become the River Cooters? The naming process develops over the course of the program. The training team encourages participants to nominate a native Texas species, which can’t repeat from previous classes. Allison Buckner surveyed our group for potential names, which were then narrowed to the three most popular: Ashe Junipers (four votes), Golden-cheeked Warblers (five votes), and River Cooters (six votes). Alas, my suggestion—scorpions—got no support other than my own. Reading the room, I threw in with the pro-cooter crowd.

Over the years, class mascots have favored mammals and birds, so river cooters represent a change. O’Hara delighted in the choice. She’s been lobbying for river cooters for years.

“‘River cooters’ has popped up in prior years but never gained popularity until 2023,” Class Training Director Mary O’Hara said, adding that she “tends to favor totems that I can imagine decorating for.”

O’Hara made the centerpieces for each table at the gala, a diorama that included a river cooter astride a stream. The only turtle figures she could find were red-eared sliders, so O’Hara changed the neck markings on each to make them look like cooters.

Give a hoot, save the coots

Laura Steffy, a mentor to the training classes, found “Save the River Cooter” t-shirts, which she gave to her mentees (and me).

Several graduates ordered their own, and we sported them at the gala. The shirts apparently were made as a joke—river cooters are not endangered, but they do face threats from collisions with boats and people who hunt them for food.

As with most classes, the new batch of graduates comes from wide-ranging backgrounds—geologists, educators, gardeners, healthcare workers—united in the desire to better understand the intricate nature of Hays County.

My wife and I are no different. When we moved to Wimberley almost seven years ago, we found ourselves with nine acres and no understanding of the land. Though we’d been in Texas most of our lives (College Station, the Dallas area, and Houston), we quickly learned how little we know about erosion control, water conservation, and the unique flora and fauna of the area. She completed the class in 2018 and loved it. We were looking for something we could do together and that would get me away from the computer and writing (oh, well!). All of us in the class were awed and inspired by the impressive list of speakers, presentations, and hands-on opportunities, and we’re just getting started. You’ll no doubt find us Cooters working alongside the Armadillos, Foxes, and Caracaras of earlier graduations.

I think I speak for the entire graduating class when I say we are proud to be River Cooters. Next year, the naming process will intensify because the chapter is expanding to two 24-week training programs. Classes will meet every other week, rather than monthly. Instead of overlapping training and volunteer work, “under the new curriculum, trainees can concentrate on learning upfront and volunteering afterwards,” O’Hara said. The spring class will graduate in November at the gala, and the fall class will be celebrated at the annual reunion in April.

Fortunately, there’s no shortage of species to use for future class totems. My advice to next year’s recruits: scorpions!

Hays County Master Naturalist Class of 2023 - The River Cooters!

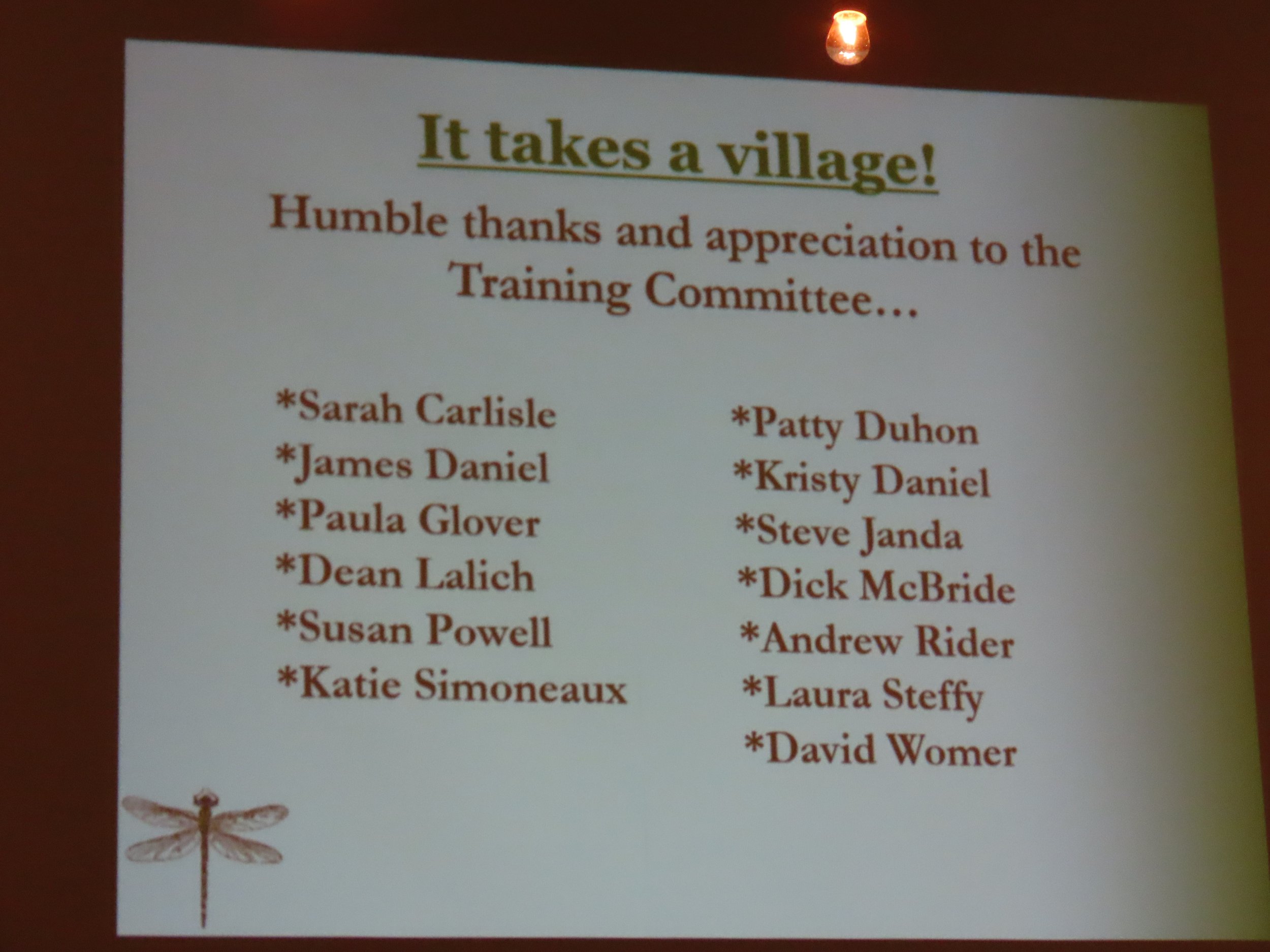

The Chapter also recognized the outstanding achievements of these 2023 Hays County Master Naturalist award winners.

Outstanding Training Committee Volunteer - James Daniel

Outstanding Chapter Volunteer - John Moore

Significant Contribution to the Chapter - Paula Glover

Special Achievement Award - Melinda Seib

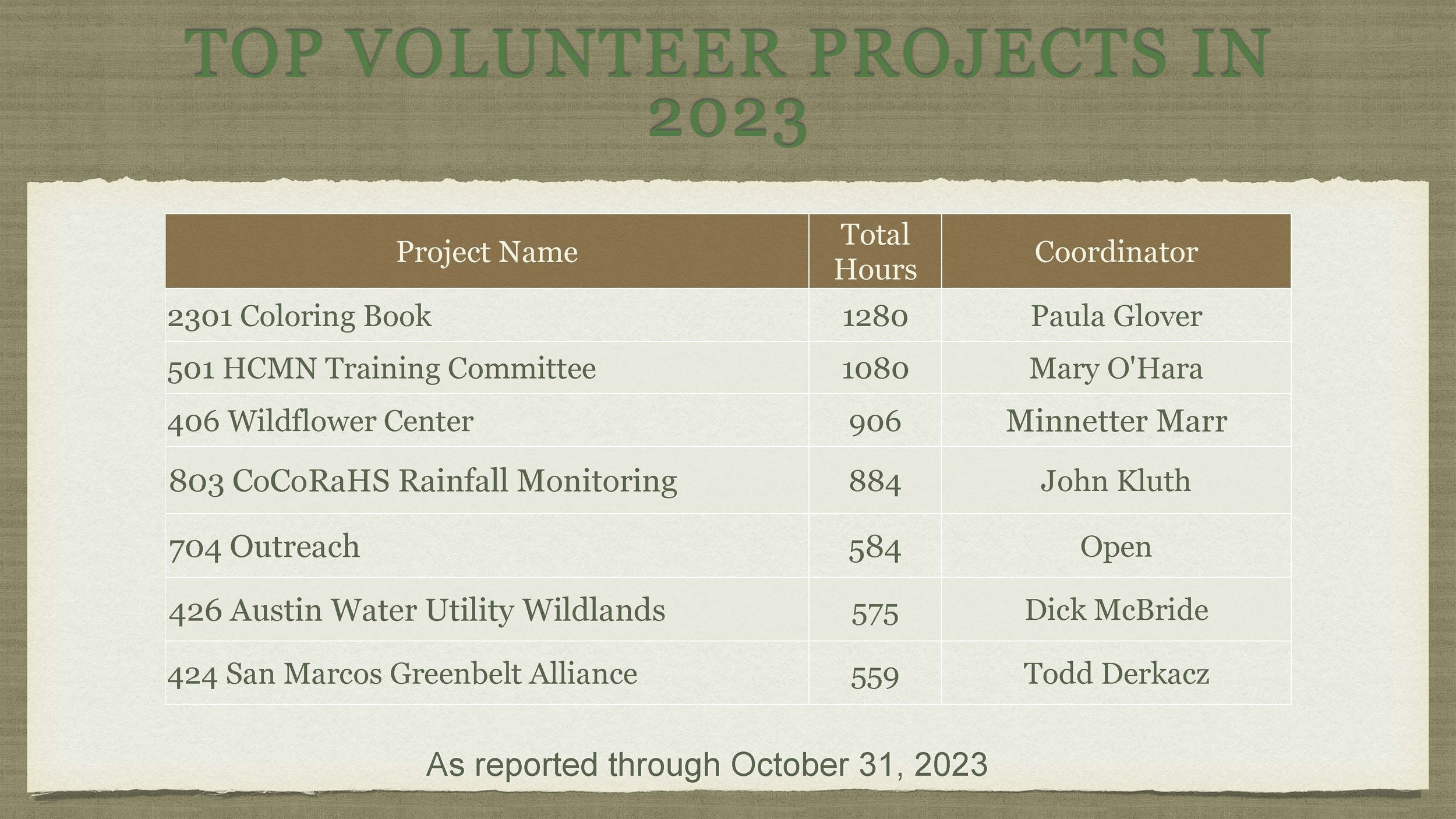

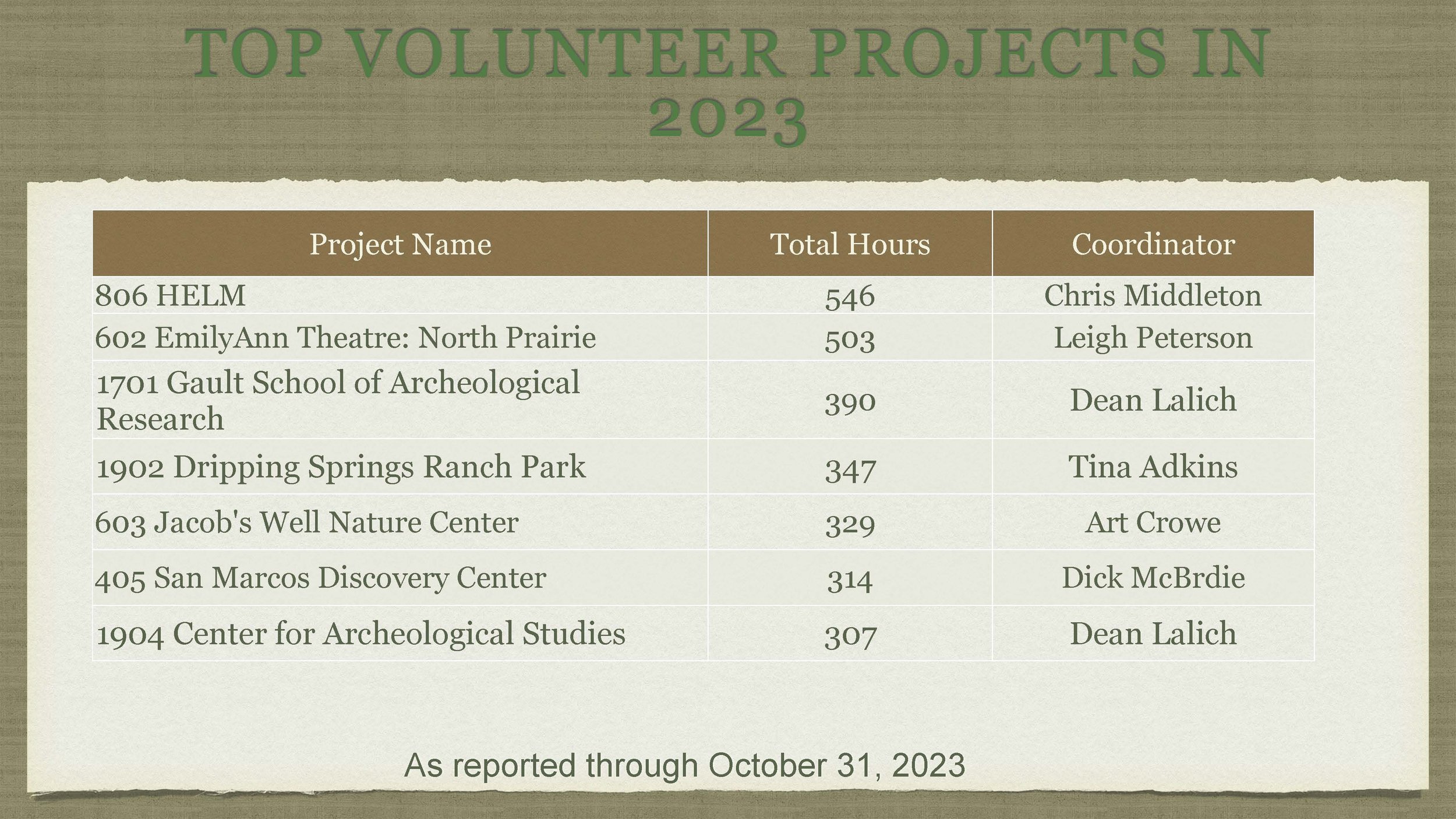

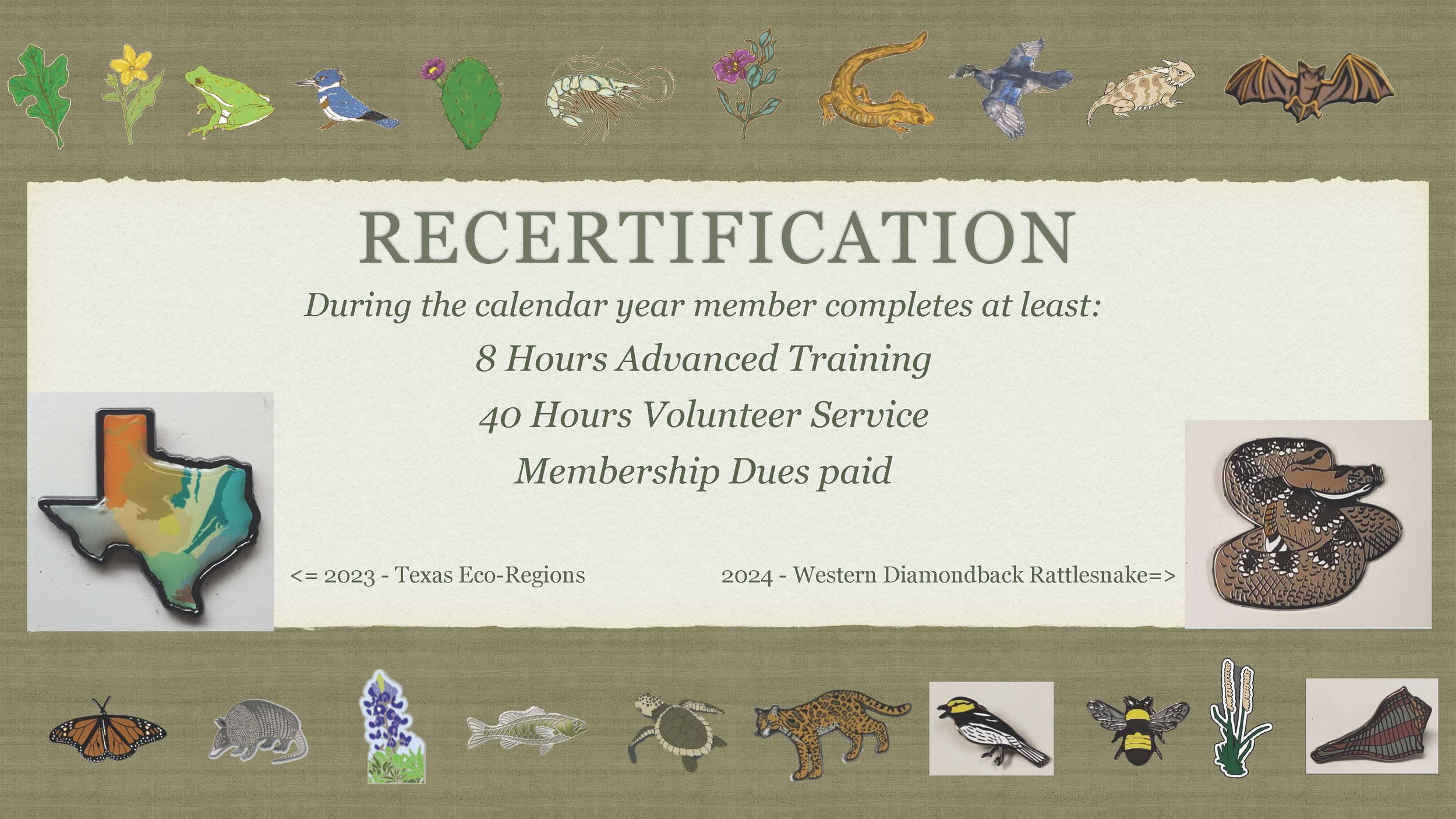

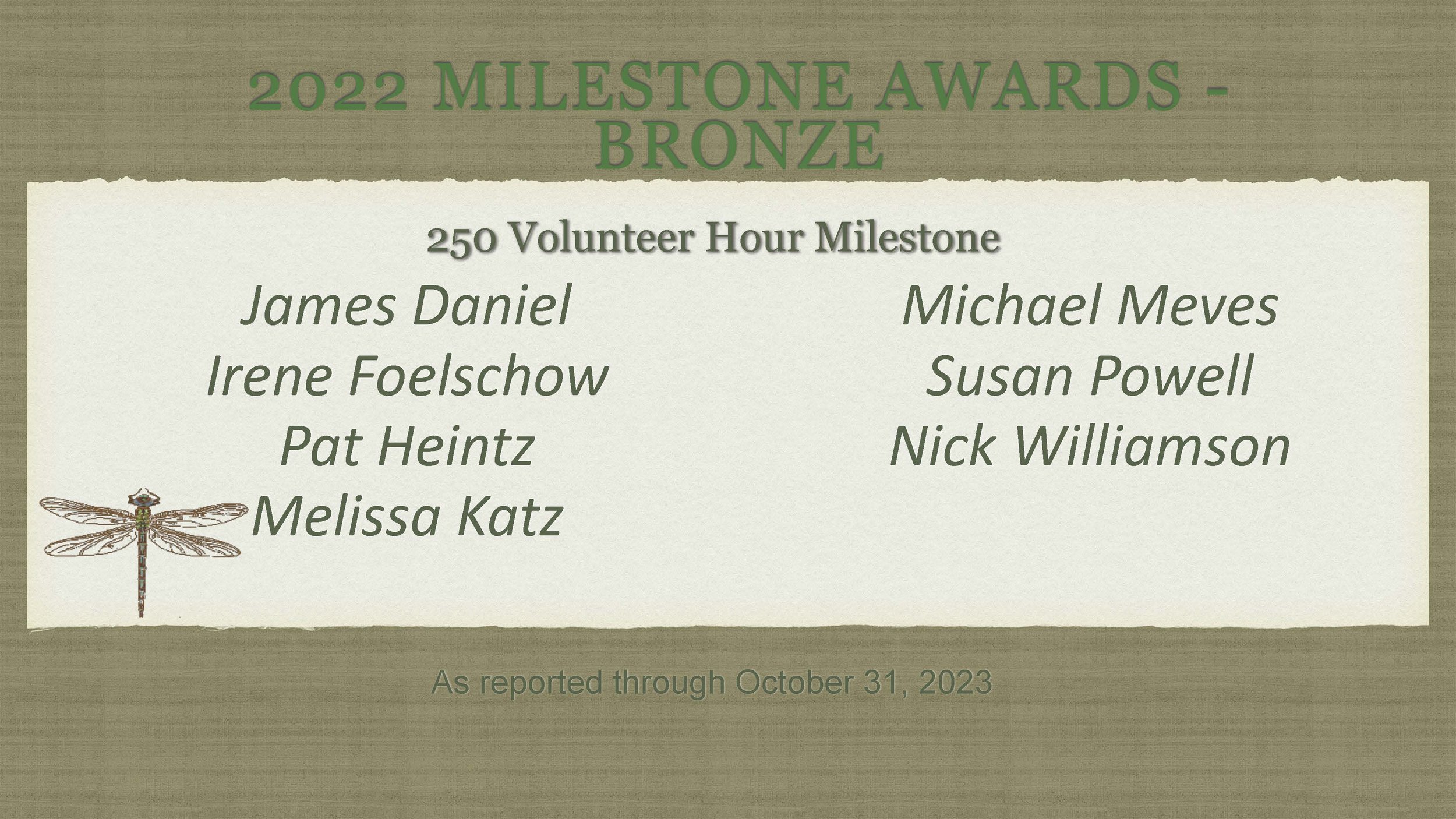

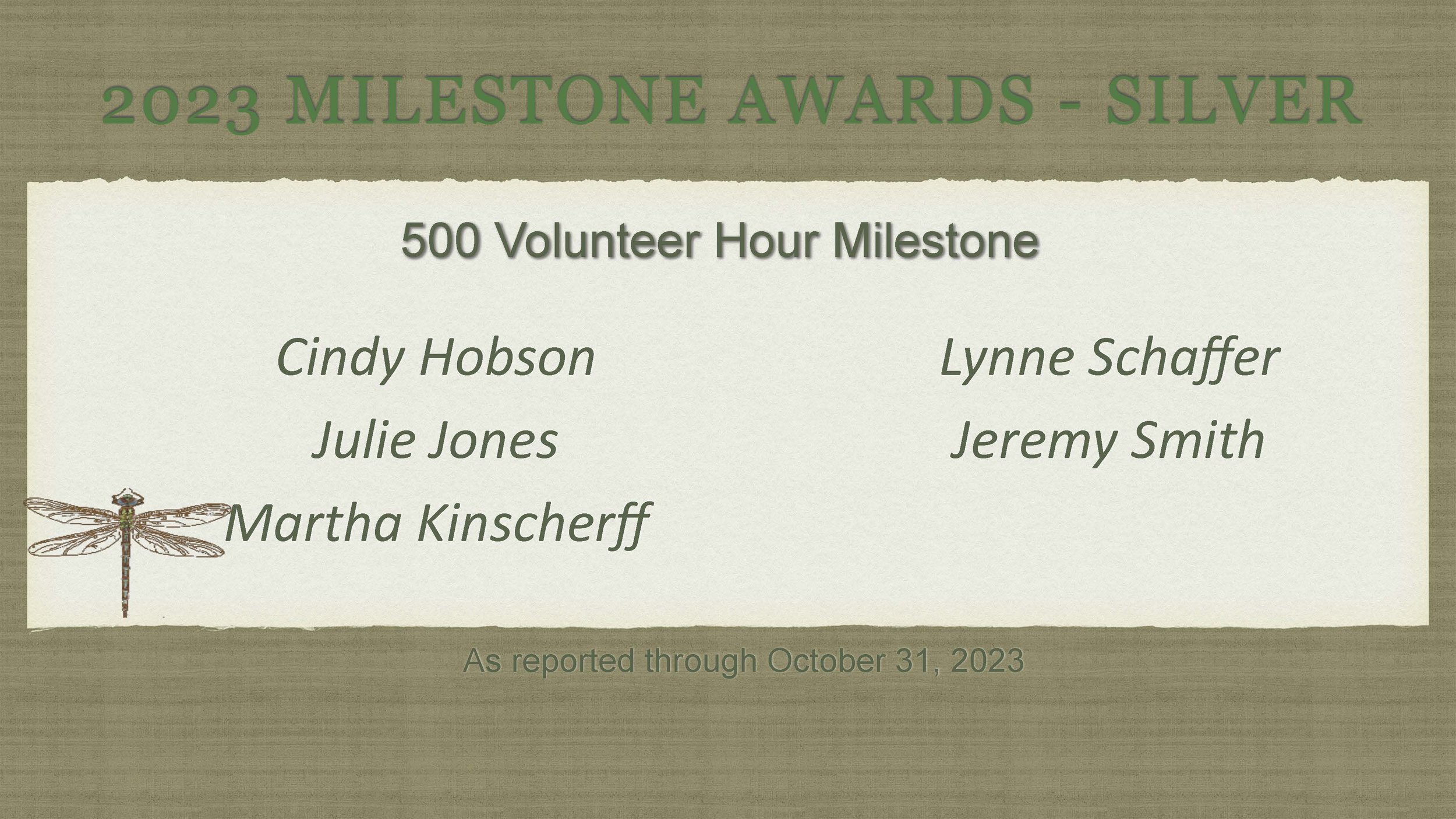

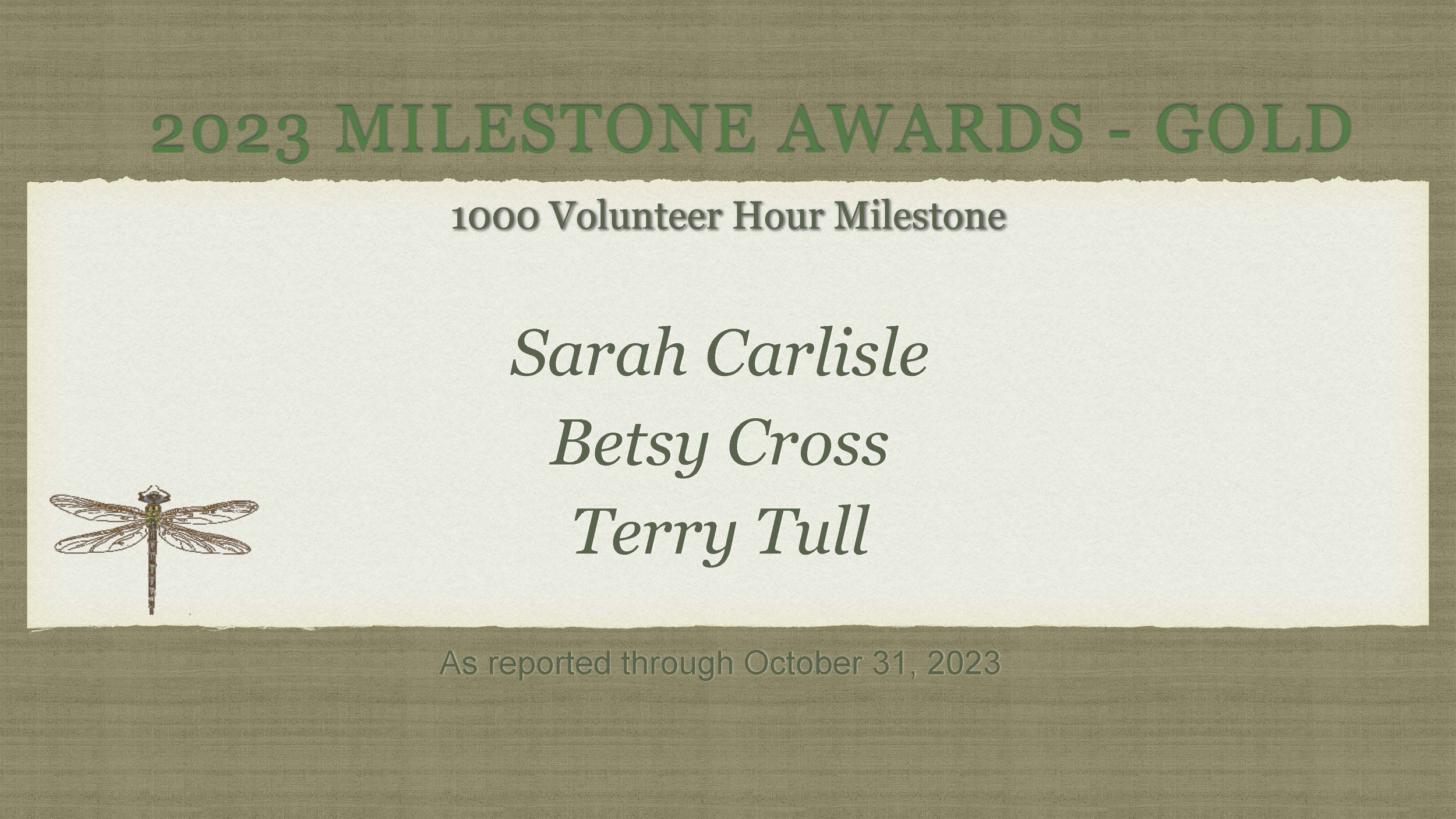

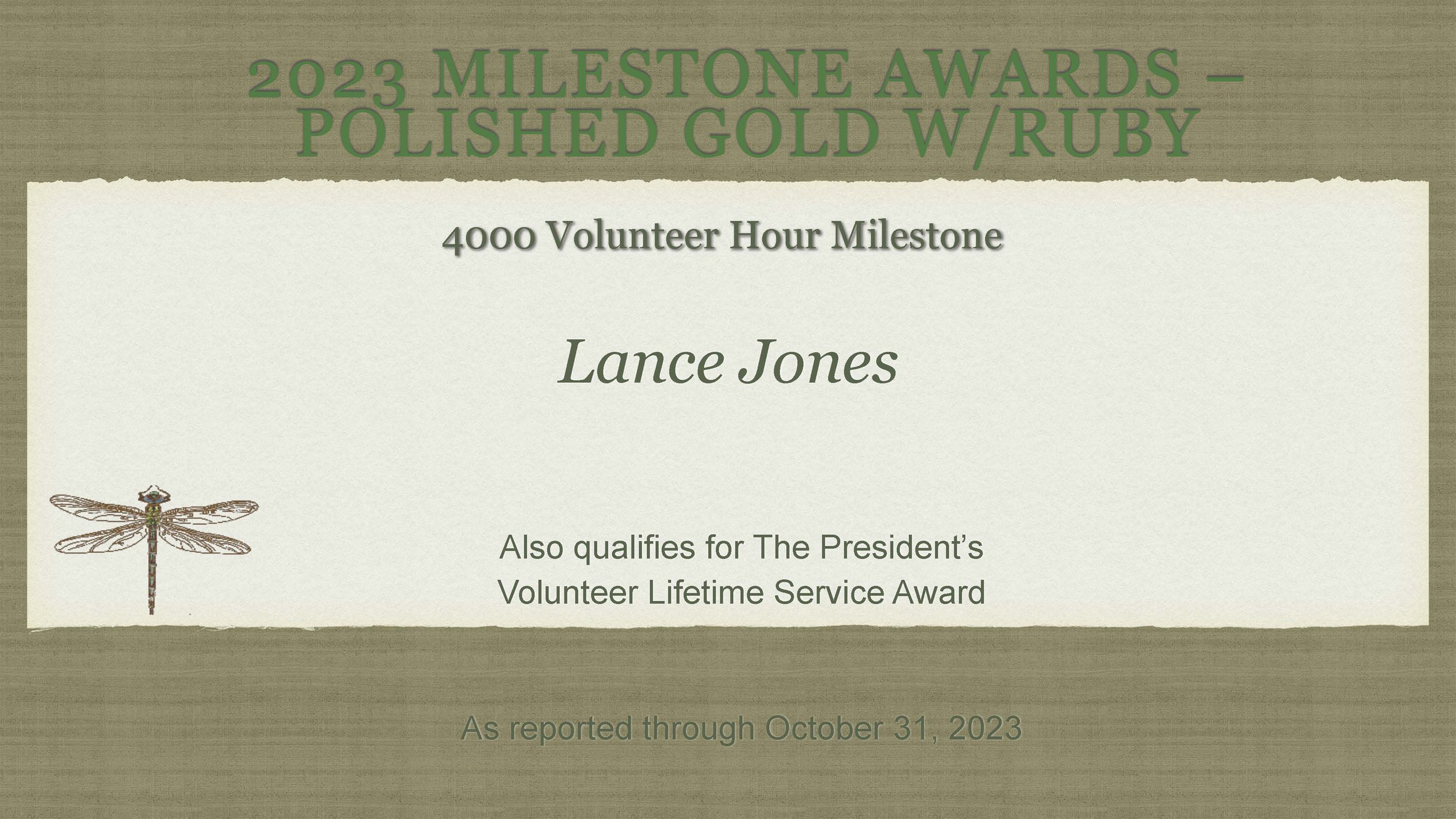

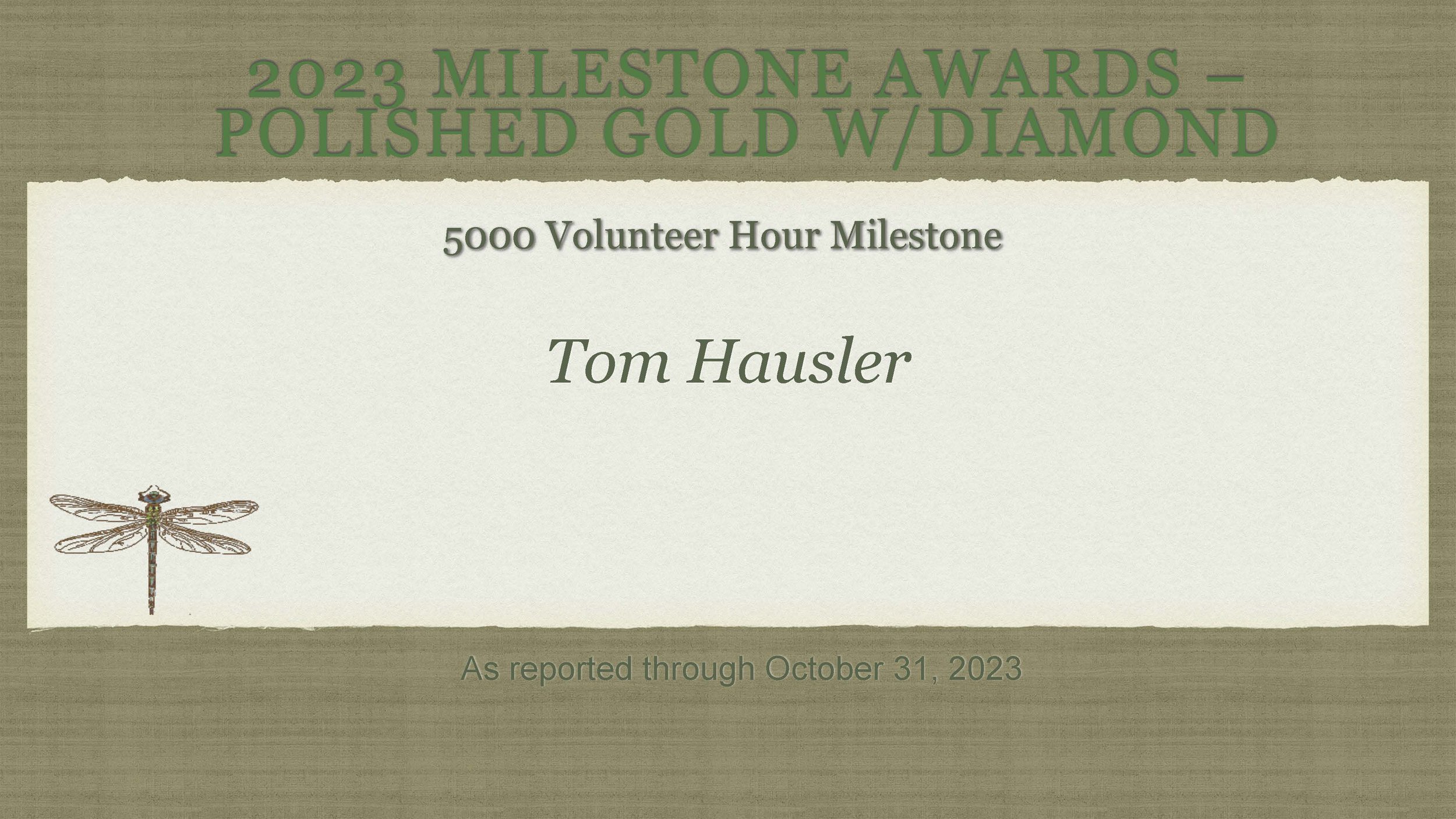

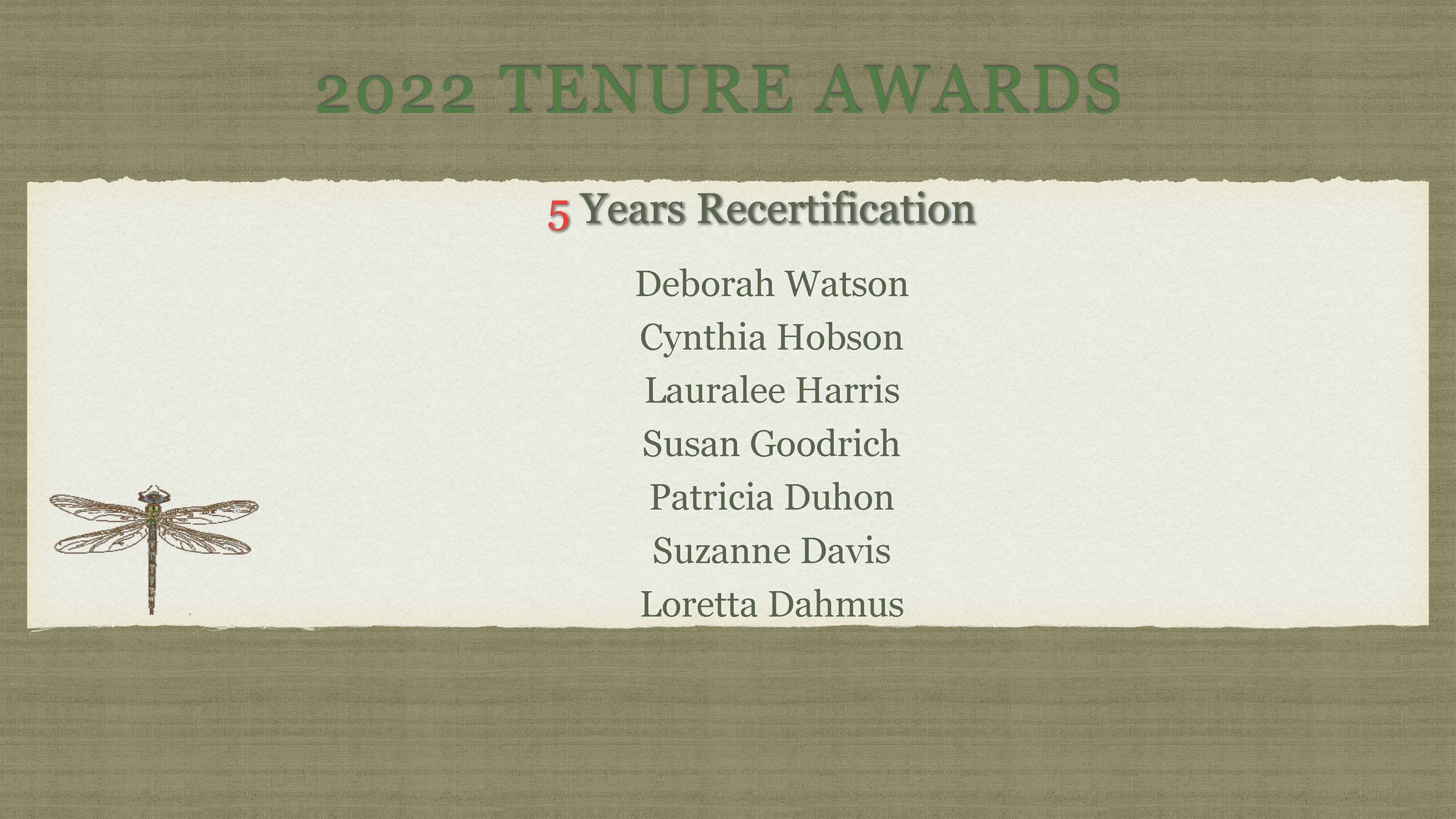

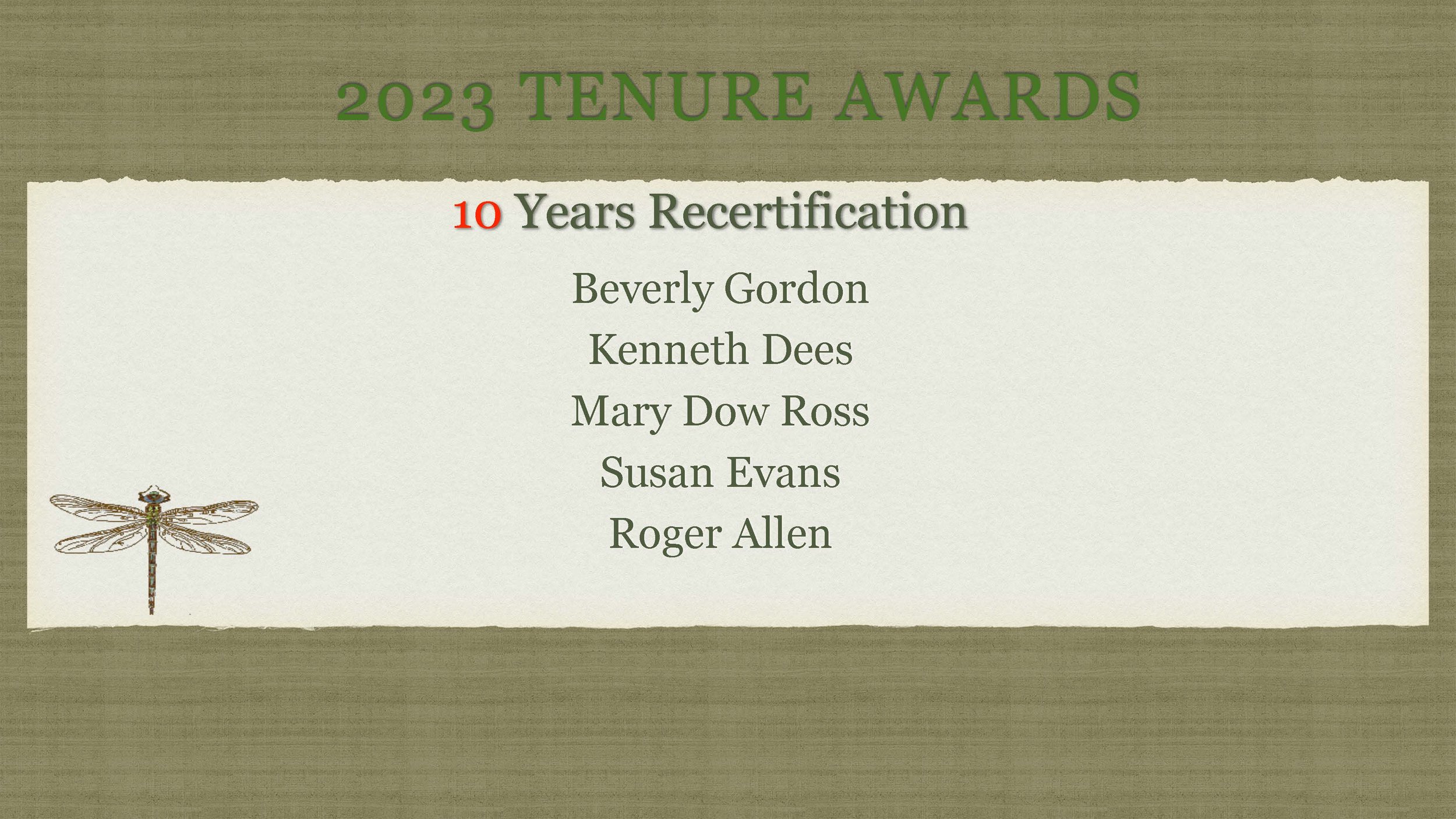

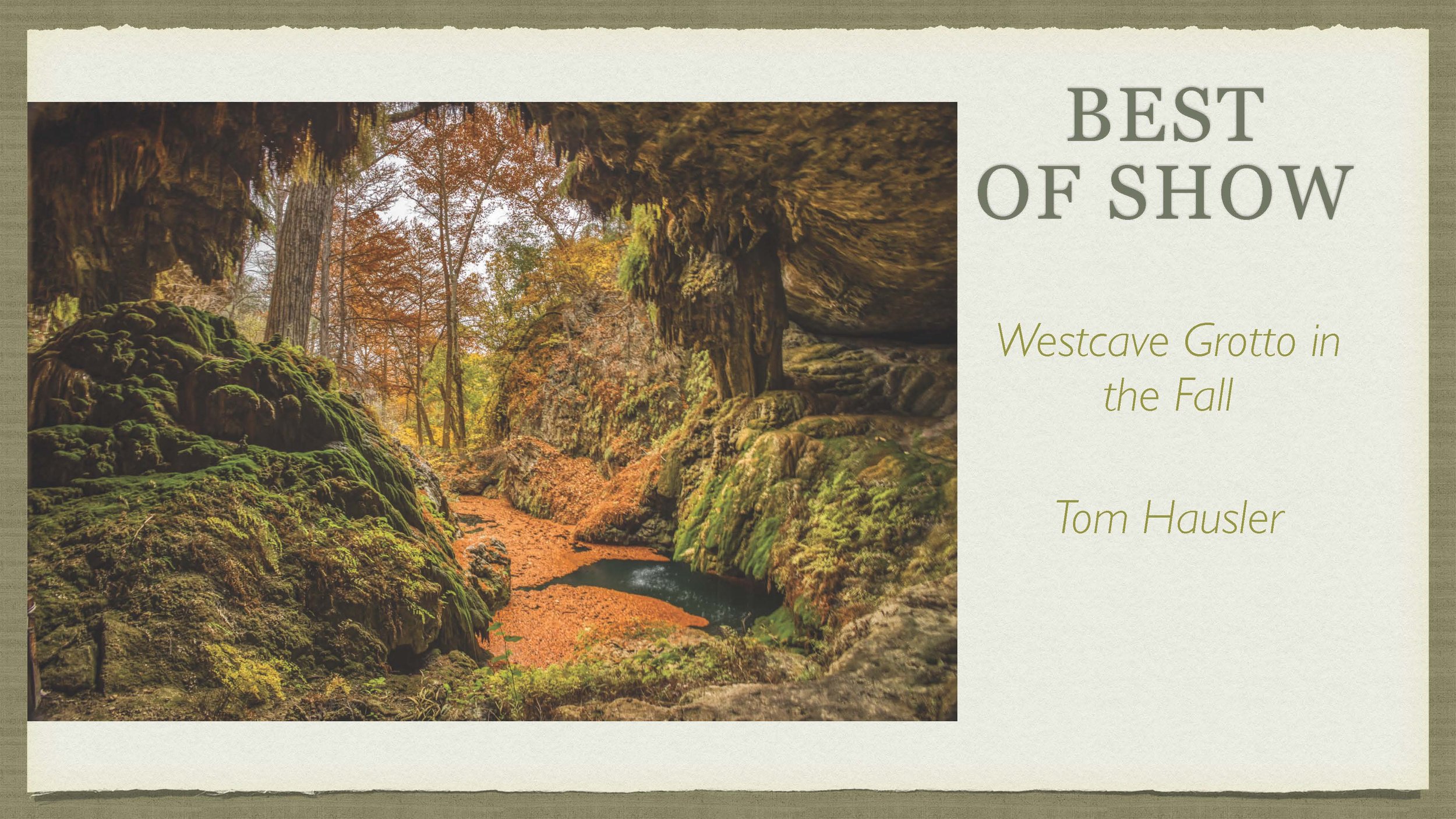

Top Volunteer Projects, Milestone Awards, Tenure Awards, and Naturescapes Photography Awards are included with Gala images in the slideshow below.

What the heck is a river cooter?

River cooters—the animals, not the graduates—are turtles (Pseudemys concinna) whose natural habitat spans from Maryland to northern Florida, west to Texas, and as far north as Indiana. Hays County is on the far western boundary of their habitat area (although cooters have been introduced to California, Washington, and British Columbia.) As the name implies, river cooters spend most of their time in the water. They go on land only to nest or bask in the sun. They are primarily plant-eaters, although they also consume animal matter, including insects, sponges, tadpoles, and small fish.

They favor clear water in depths exceeding three feet, with moderate to fast currents, rocky substrates, and plentiful aquatic vegetation. They also live in lakes and tidal marshes.

A female’s carapace can grow to almost 16 inches; a male’s 12 inches. The shells are olive, dark brown, or black with yellow- or cream-colored markings and slightly flared at the posterior. River cooters have markings similar to slider turtles on their head, neck, and limbs—post-orbital stripes are thinner than a slider’s. The females lay about 20 eggs in May and June.

River cooters can range as much as six miles, and conservationists worry they need more habitat to roam. While some states, such as Florida, prohibit the collection of river cooters, others, such as Louisiana, have refused to protect them from commercial trapping and sale. In Alabama, there are signs that river cooters are cross-breeding with red-bellied turtles and coastal plain cooters, creating a hybrid species.

The carapace provides river cooters’ primary protection from predators, with its strength dependent on the turtle’s overall size. The shell is composed of bone plates that are fused with ribs, vertebrae, and parts of the shoulder and hip, and it derives most of its strength from its shape. Although the shell typically can’t withstand attacks from larger predators such as jaguars, alligators, or tiger sharks, there have been instances of alligators, whose bite can have a force of as much as 2,900 pounds of pressure, being unable to crack a river cooter’s shell even after 15 minutes of effort. In other words, this year’s graduating class chose a resilient totem.

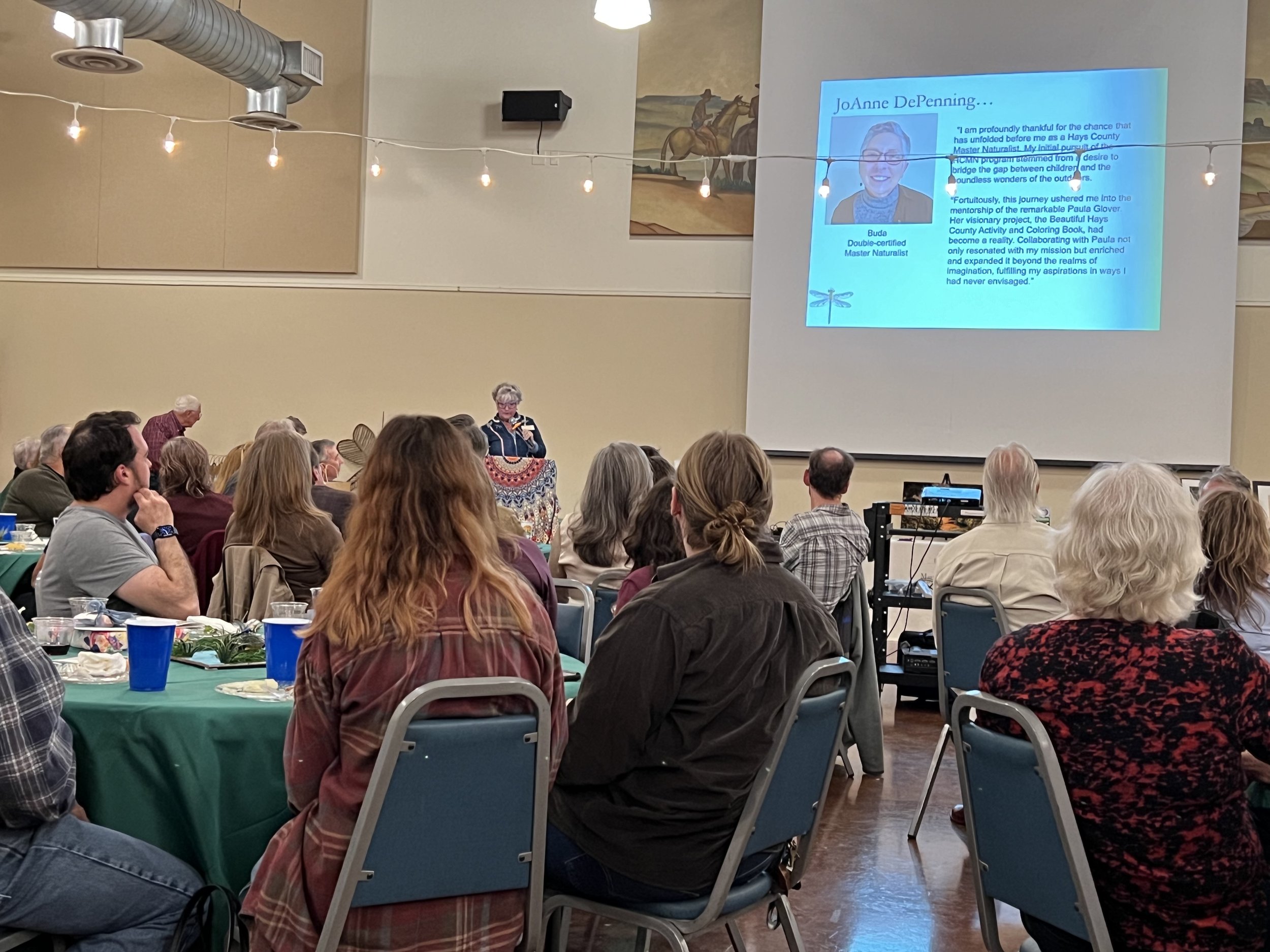

Images of the 2023 HCMN Gala

Photos contributed by Eva Frost, Mimi Cavender, and Betsy Cross.